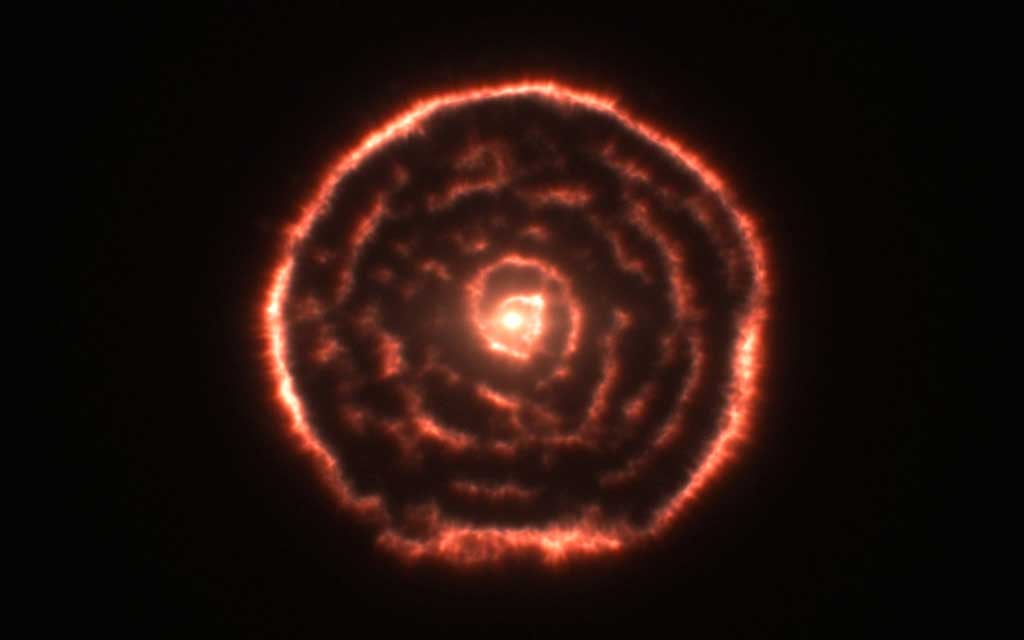

“We’ve seen shells around this kind of star before,” said Matthias Maercker from the European Southern Observatory and Argelander Institute for Astronomy, University of Bonn, Germany, “but this is the first time we’ve ever seen a spiral of material coming out from a star together with a surrounding shell.”

Because they blow out large amounts of material, red giants like R Sculptoris are major contributors to the dust and gas that provide the bulk of the raw materials for the formation of future generations of stars, planetary systems, and subsequently for life.

Even in the early science phase when the new observations were made, ALMA greatly outperformed other submillimeter observatories. Earlier observations had clearly shown a spherical shell around R Sculptoris, but neither the spiral structure nor a companion was found.

“When we observed the star with ALMA, not even half its antennas were in place,” said Wouter Vlemmings from Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden. “It’s really exciting to imagine what the full ALMA array will be able to do once it’s completed in 2013.”

Late in their lives, stars with masses up to eight times that of the Sun become red giants and lose a large amount of their mass in a dense stellar wind. During the red giant stage, stars also periodically undergo thermal pulses. These are short-lived phases of explosive helium burning in a shell around the stellar core. A thermal pulse leads to material being blown off the surface of the star at a much higher rate, resulting in the formation of a large shell of dust and gas around the star. After the pulse, the rate at which the star loses mass falls again to its normal value.

Thermal pulses occur approximately every 10,000 to 50,000 years, and they last only a few hundred years. The new observations of R Sculptoris show that it suffered a thermal pulse event about 1,800 years ago that lasted for about 200 years. The companion star shaped the wind from R Sculptoris into a spiral structure.

“By taking advantage of the power of ALMA to see fine details, we can understand much better what happens to the star before, during, and after the thermal pulse, by studying how the shell and the spiral structure are shaped,” said Maercker. “We always expected ALMA to provide us with a new view of the universe, but to be discovering unexpected new things already with one of the first sets of observations is truly exciting.”

In order to describe the observed structure around R Sculptoris, the team of astronomers also has performed computer simulations to follow the evolution of a binary system. These models fit the new ALMA observations very well.

“It’s a real challenge to describe theoretically all the observed details coming from ALMA, but our computer models show that we really are on the right track,” said Shazrene Mohamed from the Argelander Institute for Astronomy in Bonn, Germany. “ALMA is giving us new insight into what’s happening in these stars and what might happen to the Sun in a few billion years from now.”

“In the near future, observations of stars like R Sculptoris with ALMA will help us to understand how the elements we are made up of reached places like Earth. They also give us a hint of what our own star’s far future might be like,” said Maercker.