A new observatory still under construction has given astronomers a major breakthrough in understanding a nearby planetary system and provided valuable clues about how such systems form and evolve. Astronomers using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) have discovered that planets orbiting the star Fomalhaut must be much smaller than originally thought. This is the first published science result from ALMA in its first period of open observations for astronomers worldwide.

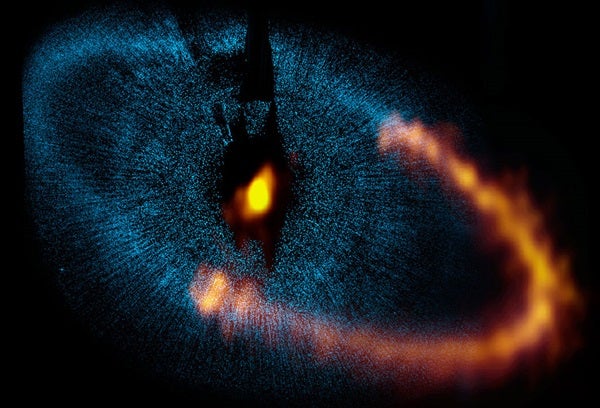

The discovery was made possible by exceptionally sharp ALMA images of a disk, or ring, of dust orbiting Fomalhaut, which lies about 25 light-years from Earth. It helps resolve a controversy among earlier observers of the system. The ALMA images show that both the inner and outer edges of the thin, dusty disk have very sharp edges. That fact, combined with computer simulations, led the scientists to conclude that the dust particles in the disk are kept within it by the gravitational effect of two planets — one closer to the star than the disk and one more distant.

Their calculations also indicated the probable size of the planets — larger than Mars but no larger than a few times the size of the Earth. This is much smaller than astronomers had previously thought. In 2008, a NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope image had revealed the inner planet, then thought to be larger than Saturn, the second-largest planet in our solar system. However, later observations with infrared telescopes failed to detect the planet.

That failure led some astronomers to doubt the existence of the planet in the Hubble image. Also, the Hubble visible-light image detected very small dust grains that are pushed outward by the star’s radiation, thus blurring the structure of the dusty disk. The ALMA observations, at wavelengths longer than those of visible light, traced larger dust grains — about 1 millimeter in diameter — that are not moved by the star’s radiation. They clearly reveal the disk’s sharp edges and ring-like structure, which indicate the gravitational effect of two planets.

“Combining ALMA observations of the ring’s shape with computer models, we can place very tight limits on the mass and orbit of any planet near the ring,” said Aaron Boley, a Sagan Fellow at the University of Florida and a leader of the study. “The masses of these planets must be small; otherwise the planets would destroy the ring.” The small sizes of the planets explain why the earlier infrared observations failed to detect them, the scientists said.

The ALMA research shows that the ring’s width is about 16 times the distance from the Sun to Earth, and is only one-seventh as thick as it is wide. “The ring is even more narrow and thinner than previously thought,” said Matthew Payne, also of the University of Florida.

The ring is about 140 times the Sun-Earth distance from the star. In our solar system, Pluto is about 40 times more distant from the Sun than Earth. “Because of the small size of the planets near this ring and their large distance from their host star, they are among the coldest planets yet found orbiting a normal star,” added Aaron Boley.

The scientists observed the Fomalhaut system in September and October of 2011, when only about a quarter of ALMA’s planned 66 antennas were available. When construction is completed next year, the full system will be much more capable. Even in this Early Science phase, though, ALMA was powerful enough to reveal the telltale structure that had eluded earlier millimeter-wave observers.

“ALMA may be still under construction, but it is already the most powerful telescope of its kind. This is just the beginning of an exciting new era in the study of discs and planet formation around other stars,” concluded European Southern Observatory astronomer and team member Bill Dent.