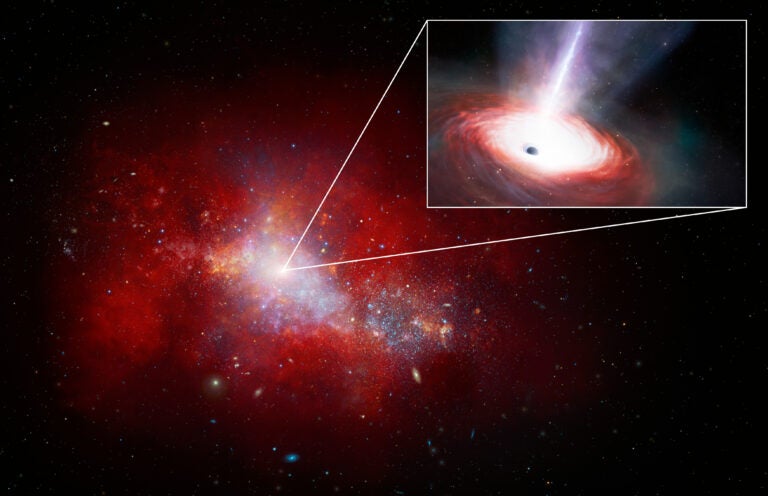

In a new proof-of-concept observation, astronomers using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) have measured the mass of the supermassive black hole at the center of NGC 1097 — a barred spiral galaxy located approximately 45 million light-years away in the direction of the constellation Fornax. The researchers determined that this galaxy harbors a black hole 140 million times more massive than our Sun. In comparison, the black hole at the center of the Milky Way is a lightweight, with a mass of just a few million times that of our Sun.

To achieve this result, the research team, led by Kyoko Onishi at SOKENDAI (the graduate university for advanced studies) in Japan, precisely measured the distribution and motion of two molecules — hydrogen cyanide (HCN) and formylium (HCO+) — near the central region of the galaxy. The researchers then compared the ALMA observations to various mathematical models, each corresponding to a different mass of the supermassive black hole. The “best fit” for these observations corresponded to a black hole weighing in at about 140 million solar masses.

A similar technique was used previously with the CARMA telescope to measure the mass of the black hole at the center of the lenticular galaxy NGC 4526.

“While NGC 4526 is a lenticular galaxy, NGC 1097 is a barred spiral galaxy. Recent observation results indicate the relationship between supermassive black hole mass and host galaxy properties vary depending on the type of galaxies, which makes it more important to derive accurate supermassive black hole masses in various types of galaxies,” Onishi said.

Currently, astronomers use several methods to derive the mass of a supermassive black hole; the technique used typically depends on the type of galaxy being observed.

Within the Milky Way, powerful optical/infrared telescopes track the motion of stars as they zip around the core of our galaxy. This method, however, is not suitable for distant galaxies because of the extremely high angular resolution it requires.

In place of stars, astronomers also track the motion of megamasers (astrophysical objects that emit intense radio waves and are found near the center of some galaxies), but they are rare; the Milky Way, for example, has none. Another technique is to track the motion of ionized gas in a galaxy’s central bulge, but this technique is best suited to the study of elliptical galaxies, leaving few options when it comes to measuring the mass of supermassive black holes in spiral galaxies.

The new ALMA results, however, demonstrate a previously untapped method and open up new possibilities for the study of spiral and barred spiral galaxies.

“This is the first use of ALMA to make such a measurement for a spiral or barred spiral galaxy,” said Kartik Sheth from the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in Charlottesville, Virginia. “When you look at the exquisitely detailed observations from ALMA, it’s startling how well they fit in with these well tested models. It’s exciting to think that we can now apply this same technique to other similar galaxies and better understand how these unbelievably massive objects affect their host galaxies.”

Since current theories show that galaxies and their supermassive black holes evolve together — each affecting the growth of the other — this new measurement technique could shed light on the relationship between galaxies and their resident supermassive black holes.

Future observations with ALMA will continue to refine this technique and expand its applications to other spiral-type galaxies.