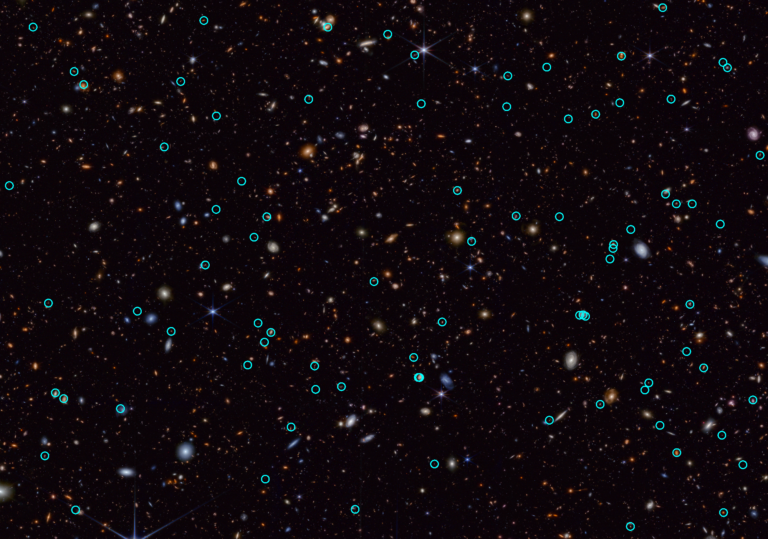

Lots of people wonder if the colors they see in images of celestial objects (like the ones from the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope atop Mauna Kea) are real or the result of some sort of imaginative image processing. Are all those reds, blues, and greens really there? Can we see them through a telescope?

Nebulae come in a variety of beautiful colors that are captured by astroimagers and reproduced in Astronomy. But why don’t we see these vivid colors through telescopes? The answer, quite simply, is that most objects are not bright enough to trigger the color receptors in our eyes.

Human vision is divided into two types. “Photopic” vision is the type we employ mainly in the daytime, when we’re looking at objects flooded with light. It’s sometimes just called “color vision” and involves the receptors in the eye known as cones. “Scotopic” vision is used under low levels of illumination and involves the receptors called rods. For our photopic vision to be triggered, the object we’re looking at must be reasonably bright, or our telescope must be large enough to make it appear bright. Take the colors of nebulae, for example.

You’re more likely to see color in deep-sky objects of a different type — planetary nebulae. Planetary nebulae are generally not large, so their light is concentrated in a relatively small area of an eyepiece’s field of view. The Blue Snowball (NGC 7662) in Andromeda is a great example. We see objects like this as colored because telescopes collect much more light than our eyes. The bigger the scope, the more colored nebulae it will show you.

The detectors used by amateur astrophotographers also have a big advantage over our eyes. A film or CCD camera can collect light from a celestial object over seconds, minutes — even hours. The human eye is limited to a 1/30-second exposure. That is, our brain refreshes our view 30 times a second. This limitation (similar to a camera shutter) allows only so much light into the eye at any one time, and it guarantees cameras will record much greater detail and color. So enjoy the pictures — they’re real.

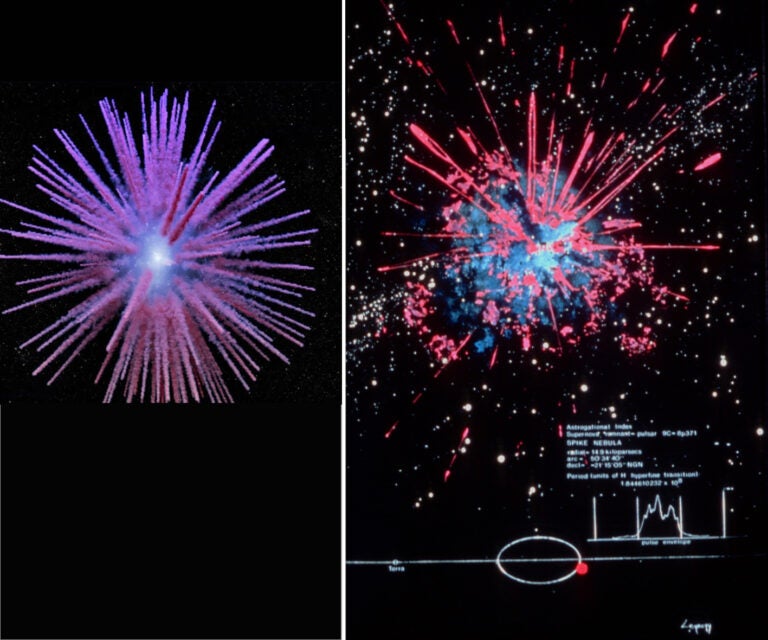

Most visible nebulae are “emission” nebulae (and, yes, there are combination emission/reflection nebulae). An emission nebula shines because new, hot stars within the cloud are exciting the atoms of gas (raising them to a higher energy level). Individual atoms of gas in the nebula absorb the energy from starlight. Because the atoms can’t hold this extra energy for long, they re-emit it as light with a distinctive red color.