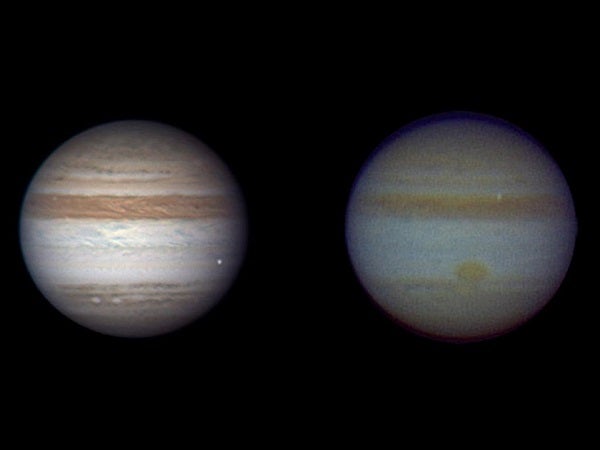

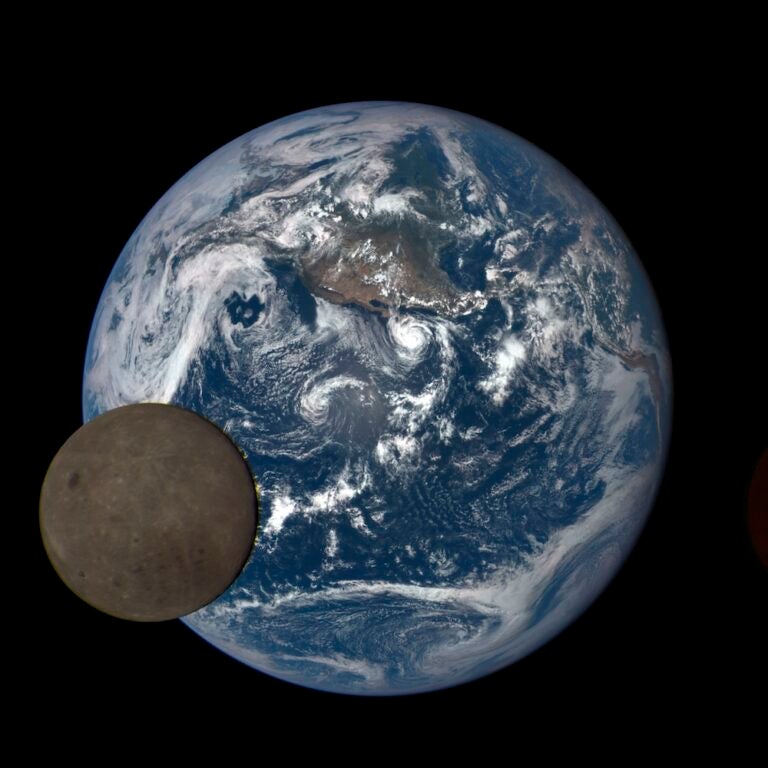

The color image on the right was taken by amateur astronomer Masayuki Tachikawa of Kumamoto, Japan, on August 20, 2010. The fireball appears in the upper right of Tachikawa’s image.

Amateur astronomers using backyard telescopes were the first to detect two small objects that burned up in Jupiter’s atmosphere June 3 and August 20.

Professional astronomers at NASA and other institutions followed up on the discoveries and gathered detailed information on the objects, which produced bright spots on Jupiter. The object that caused the June 3 fireball was estimated to be 30 to 40 feet (8 to 13 meters) in diameter — comparable in size to asteroid 2010 RF12 that flew by Earth September 8.

The June 3 fireball released 5 to 10 times less energy than the 1908 Tunguska meteoroid, which exploded 4 to 6 miles (6 to 10 kilometers) above Earth’s surface with a powerful burst that knocked down millions of trees in a remote part of Russia. Scientists continue to analyze the August 20 fireball, but think it was comparable to the June 3 object.

“Jupiter is a big gravitational vacuum cleaner,” said Glenn Orton, an astronomer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, and co-author of a paper that appeared online Thursday in Astrophysical Journal Letters. “It is clear now that relatively small objects that are remnants from the formation of the solar system 4.5 billion years ago still hit Jupiter frequently. Scientists are trying to figure out just how frequently.”

The lead author of the paper in Astrophysical Journal Letters is Ricardo Hueso of the Universidad del Pais Vasco in Bilbao, Spain.

Before amateurs spotted the June 3 impact, scientists were unaware collisions that small could be observed. Anthony Wesley, an amateur astronomer from Australia who discovered a dark spot on Jupiter in July 2009, was the first to see the tiny flash June 3. Amateur astronomers had trained their backyard telescopes on Jupiter that day because the planet was in a particularly good position for viewing. Wesley was watching real-time video from his telescope when he saw a 2.5-second-long flash of light near the edge of the planet.

“It was clear to me straight away it had to be an event on Jupiter,” Wesley said.

Another amateur astronomer, Christopher Go, of Cebu, Philippines, confirmed that the flash also appeared in his recordings. Professional astronomers, alerted by e-mail, looked for signs of the impact in images from larger telescopes, including NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile, and Gemini Observatory telescopes in Hawaii and Chile. Scientists saw no thermal disruptions or typical chemical signatures of debris, which allowed them to put a limit on the size of the object.

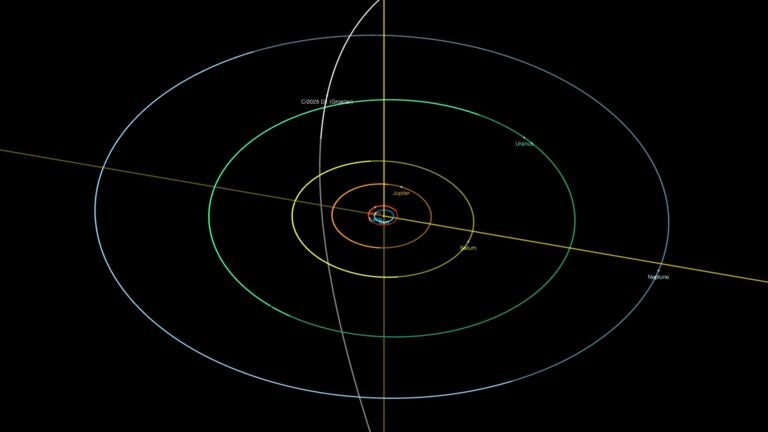

Based on the data, the astronomers deduced the flash came from an object — probably a small comet or asteroid — burning up in Jupiter’s atmosphere. The object likely had a mass of about 1 to 4 million pounds (500 to 2,000 metric tons), about 100,000 times lighter than that other object that hit Jupiter in July 2009.

The second fireball, on August 20, was first detected by Japanese amateur astronomer Masayuki Tachikawa. It flashed for about 1.5 seconds and left no debris observable by a large telescope.

“It is interesting to note that while Earth gets smacked by a 10-meter-sized object about every 10 years on average, it looks as though Jupiter gets hit with the same-sized object a few times each month,” said Don Yeomans, manager of the Near-Earth Object Program Office at JPL. “The Jupiter impact rate is still being refined and studies like this one help to do just that.”

Previous models of collisions this size on Jupiter had predicted as few as one and as many as 100 such collisions a year. Scientists now believe the frequency must be closer to the high end of the scale.