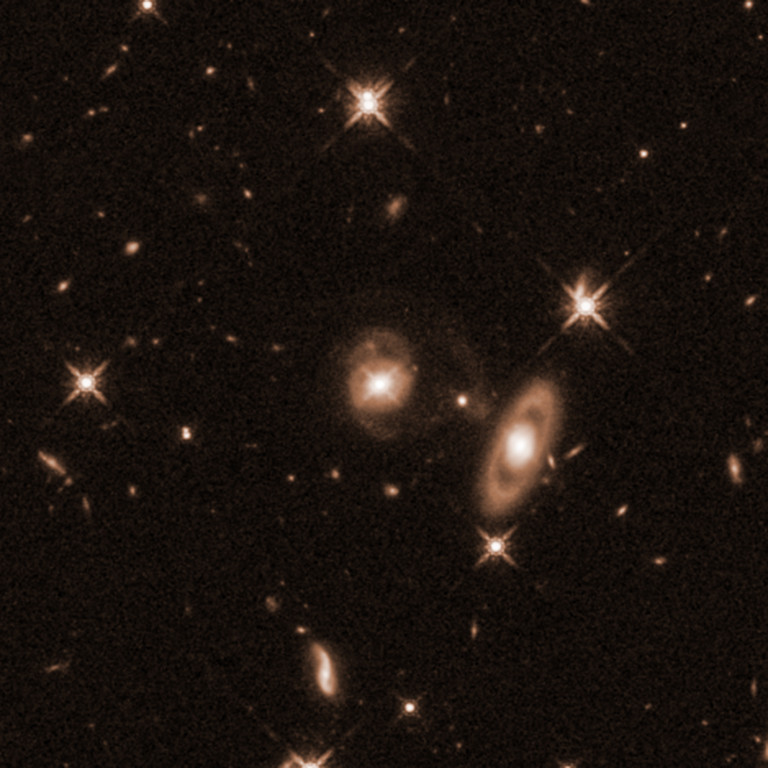

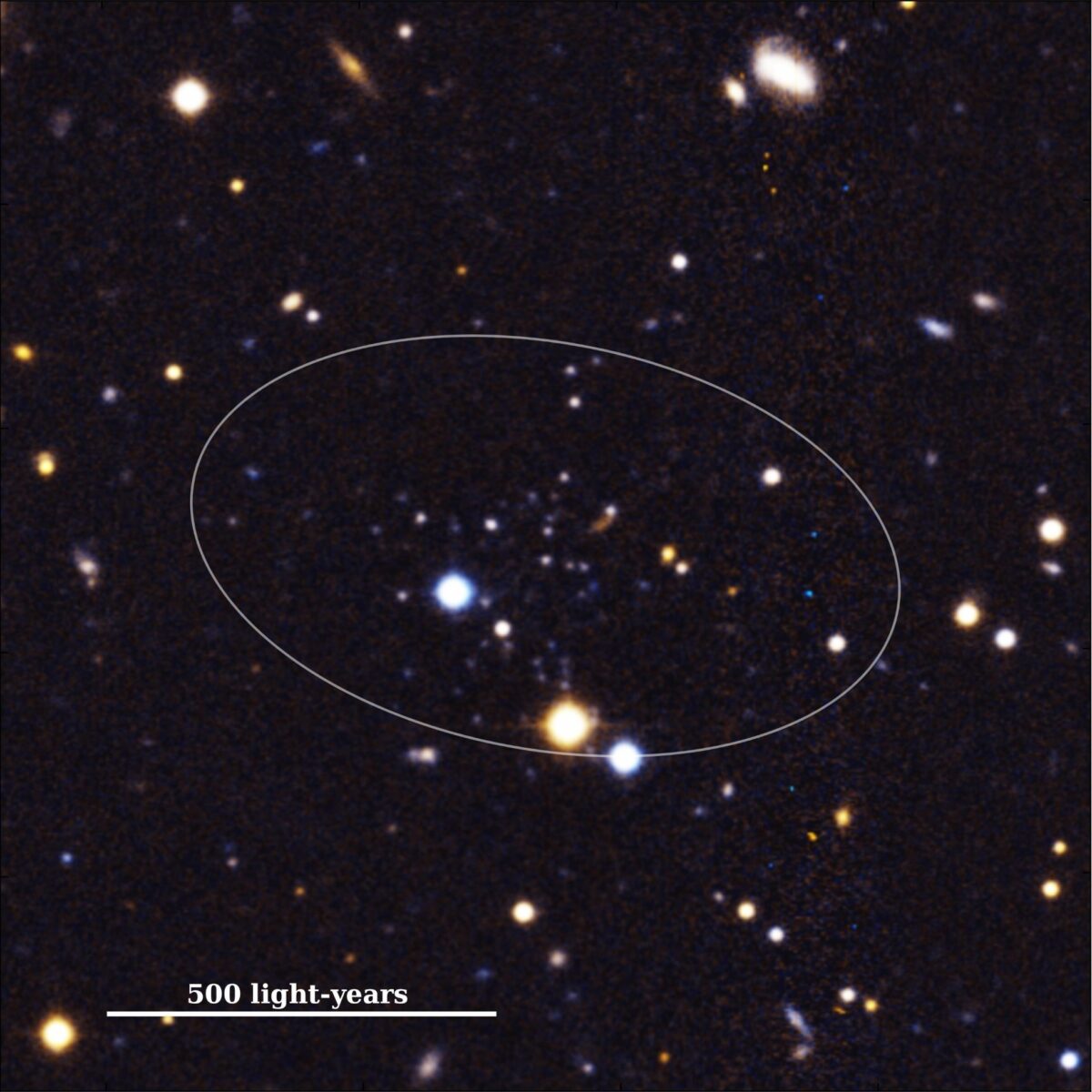

Astronomers at the University of Michigan have discovered a new satellite of the Andromeda Galaxy (M31), the Milky Way’s closest major galactic neighbor, and it has broken the record for the faintest such galaxy yet discovered. Both the Milky Way and Andromeda are known to have a slew of smaller galaxies that orbit them, caught in their larger brethren’s gravitational grip but not torn apart by tidal forces.

But the satellites of the Milky Way and M31 show different evolutionary histories, and this new galaxy, dubbed Andromeda XXXV, is no exception. The question of why Milky Way satellites appear so different from Andromeda satellites is not one Andromeda XXXV can answer on its own, but it does represent another piece of an important galactic puzzle.

The discovery was led by Marcos Arias, who was an undergraduate at the University of Michigan while completing the research. (Arias has since graduated and is pursuing a post-baccalaureate research position.) Their research was published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters on March 11.

Big mysteries from little galaxies

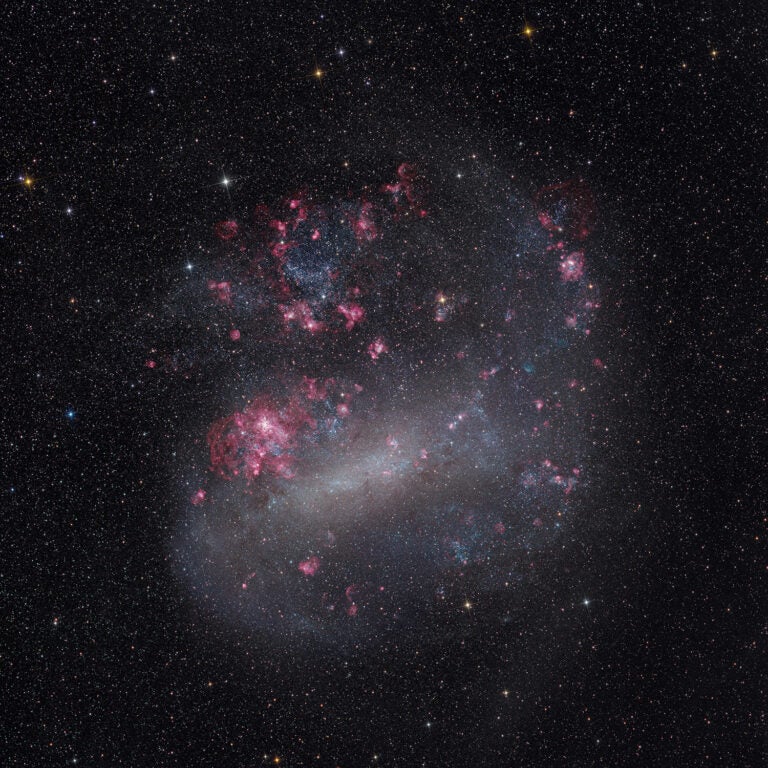

Andromeda XXXV is what astronomers term an ultra-faint dwarf galaxy, which is exactly what it sounds like. These tiny, dim stellar conglomerations are common in the universe, but tricky to observe, thanks to their low luminosities. Astronomers can find many of them around the Milky Way, since they’re relatively close, but they’re simply too faint to see beyond our local neighborhood. As space telescopes improved over just the past few decades, they discovered that the ones visible around M31 appear different in at least one key way.

The Milky Way’s small satellites appear to have all shut off their star formation some 10 billion years ago — a long time even in cosmological reckoning. By contrast, many of M31’s satellites kept their star formation engines churning for billions of years more, shutting off only in the past 5 billion years or so. Astronomers aren’t sure why the difference exists.

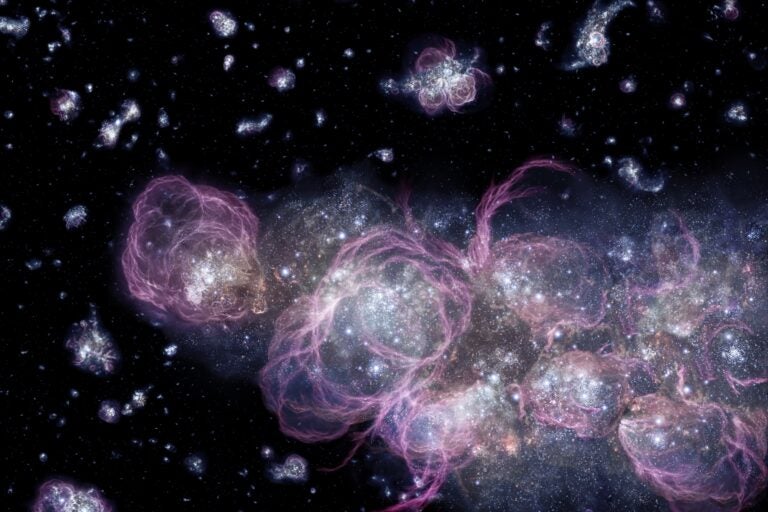

To make stars, galaxies of any size need large reservoirs of cold gas. Even for large galaxies, the availability of such reservoirs varies with time and conditions. But small galaxies, especially ultra-faint examples like Andromeda XXXV, face additional challenges. Within the first billion years after the Big Bang, during the universe-wide event known as reionization, the intense energy from hot young stars ionized the cosmos. It would have been difficult for small galaxies to hold onto their gas, and much of it would have boiled away.

When the only small galaxies astronomers could observe were those around the Milky Way, based on what they saw, they assumed that all small galaxies in the universe had been stripped of gas in their youth. But the discovery of faint satellites around M31 showed that some satellite galaxies managed to hold onto gas into later epochs.

The puzzle is why most Milky Way satellites appear to have stopped forming stars long before their counterparts around Andromeda. Perhaps their larger cousins siphoned gas away. Or the dwarf galaxies blew out their own gas through supernova explosions.

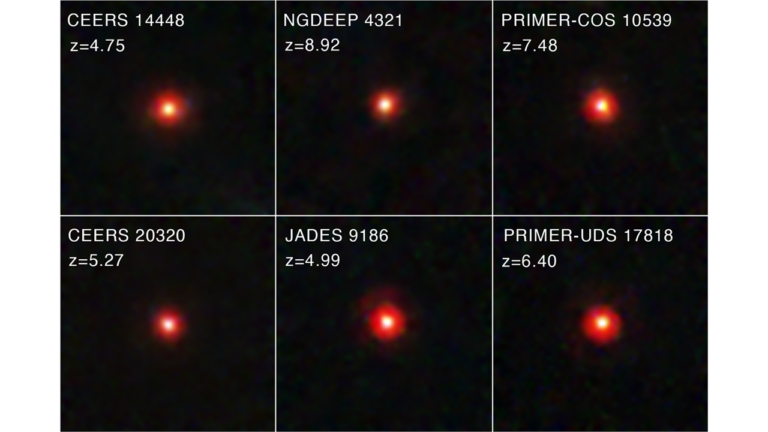

New record

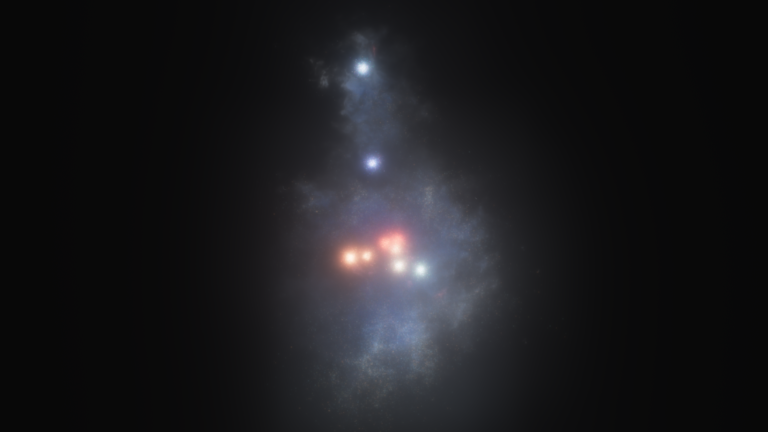

Andromeda XXXV doesn’t answer this puzzle, but it does add a new piece. Because it is the faintest satellite galaxy yet discovered, it should rank among the smallest, and therefore most susceptible to reionization heating. Yet it continues the trend of M31 satellites whose star formation shut off much later in the game.

The authors stress that because the galaxy is so faint, there is still much to learn about Andromeda XXXV. The researchers’ detailed observations were completed with Hubble, but the newer James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has yet to view the system. JWST or NASA’s upcoming Roman Space Telescope could nail down the galaxy’s distance, and therefore size, more accurately, as well as yield more detailed information about the stellar populations within the galaxy and when exactly they formed and, just as importantly, stopped forming.

Sometimes, it’s the smallest members of a community that ask the most important questions.