Finding a place to put a major new observatory isn’t easy. One of the most important factors in selecting a site for a large telescope is the level of “seeing,” the unsteadiness of an astronomical image, but a variety of other natural factors come into play as well. Seismic and auroral activity, precipitation, cloud cover, pollution, wind speeds, and heat emitted from the atmosphere all can diminish the scientific return from an observatory. Astronomers have to examine human factors, too — things like accessibility, light pollution, available infrastructure, and the cost of operating the facility.

As luck would have it, the most remote and least habitable place on Earth happens to be just about perfect.

Lawrence and his colleagues estimate that a 4-meter telescope at Dome C could produce optical images of equivalent resolution to the Hubble Space Telescope about 10 percent of the time. Observe in the near infrared, and that number rises to 50 percent.

Modern observatories improve their already excellent seeing conditions with hardware called adaptive optics. Adaptive-optics systems use lasers or star images to track the atmosphere’s distorting effects, then flex the telescope’s mirror using computer-controlled actuators to partially cancel the distortion. With sufficiently good seeing, a telescope equipped with adaptive optics could, in principle, produce images with resolutions as high as the theoretical maximum, a limit imposed by the way light diffracts around structures inside the scope.

Antarctica is uniquely suited for optical and infrared astronomy, noted Roger Angel, director of the Steward Observatory Mirror Laboratory in Tucson. He was aware of the Australian team’s results in June, when he presented a paper on the best sites for future telescopes at the International Society for Optical Engineering (SPIE) Astronomical Telescopes and Instrumentation conference in Glasgow, Scotland. “Ground-based telescopes with adaptive optics will be capable of diffraction-limited imaging down to a short-wavelength limit set by . . . atmospheric turbulence,” he wrote. “The best conditions are on the high Antarctic plateau, where recent measurements at Dome C show turbulence typically half the amplitude of the best temperate sites, with temporal evolution at half the speed.”

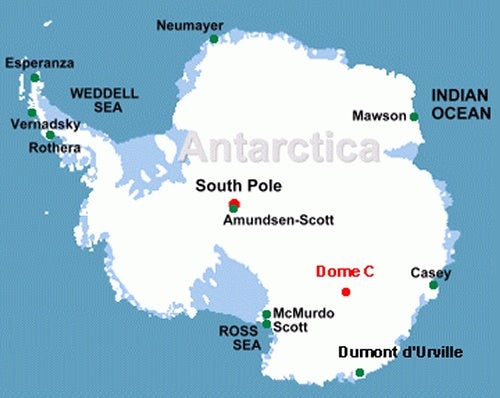

So, in January 2003, they built the Automated Astrophysical Site Testing International Observatory (AASTINO) at Concordia station. Heat and power came from jet-fuel-powered WhisperGen engines, an Iridium satellite phone provided communications; computer controls automated a suite of site-testing instruments. Ashley could view AASTINO’s health on his Internet-capable cell phone; on a few occasions where human intervention was necessary, he even sent commands to the facility.

A critical piece of hardware for AASTINO was the Multi-Aperture Scintillation Sensor (MASS) invented by Andrei Tokovinin — also on Lawrence’s team — and colleagues at the Sternberg Astronomical Institute of Moscow University. This instrument makes it possible to measure seeing accurately with a small, 8.5-centimeter telescope, which reduced cost and eased automation.

Construction of a fully robotic, 0.8m infrared telescope has already begun at Dome C. Plans call for the Italian Robotic Antarctic Infrared Telescope (IRAIT) to begin observations in December 2005.

Ashley and his colleagues aim to build a 2m optical telescope as a test bed. “A 2m at Dome C would be a general purpose facility that simply has better performance by far than a similar telescope at a mid-latitude site; an 8m at Dome C would blow away all the existing ground-based telescopes, and compete with planned ELTs [Extremely Large Telescopes],” he told Astronomy. “An interferometer at Dome C could directly image exoplanets,” he noted.

“A telescope there would perform as well as a much larger one anywhere else on Earth. It’s nearly as good as being in space,” said Will Saunders of the Anglo-Australian Observatory.

In June, Saunders presented his concept for an unusual telescope well matched for Dome C’s conditions at the SPIE conference in Glasgow. Saunders estimates his design would cost about a fifth as much as one of the planned ELTs, with mirrors 30m to 100m across and costs starting at $700 million. For comparison, the Hubble Space Telescope cost about $2.2 billion at launch.

“With this simple telescope you could do the exquisite imaging that the ELTs plan to do, at a fraction of their cost,” Saunders explained. “But, unlike them, this telescope would also be a great survey instrument, able to map the whole sky with Hubble-like clarity.”

The Antarctic plateau may soon become astronomy’s ice field of dreams.