Anthropology professor Vance T. Holliday and others take issue with claims that a comet strike led to the demise of Paleo-Indian mega-fauna hunters during the Pleistocene.

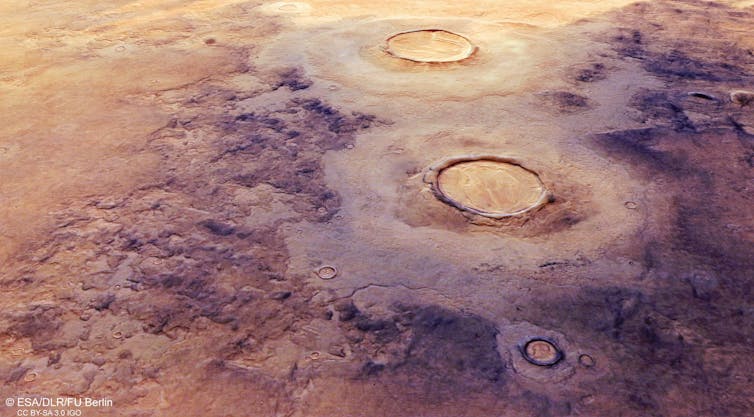

The notion of an object such as a comet or asteroid striking Earth and wiping out entire species is compelling, and sometimes there’s good evidence for it. Most scientists now agree that a very large object from space crashed into what is now the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico 65 million years ago, altering climate patterns sufficiently to end the age of the dinosaurs.

Supporting evidence backed up the theory, and while not everyone in the scientific community was on board at first, it’s now generally accepted.

For about 3 years, a similar controversy has been brewing about the end of the Pleistocene, when ice sheets covered large parts of the planet and animal behemoths foraged the landscape. Prehistoric hunters developed sophisticated strategies and tool kits for bringing down mammoths and other mega fauna.

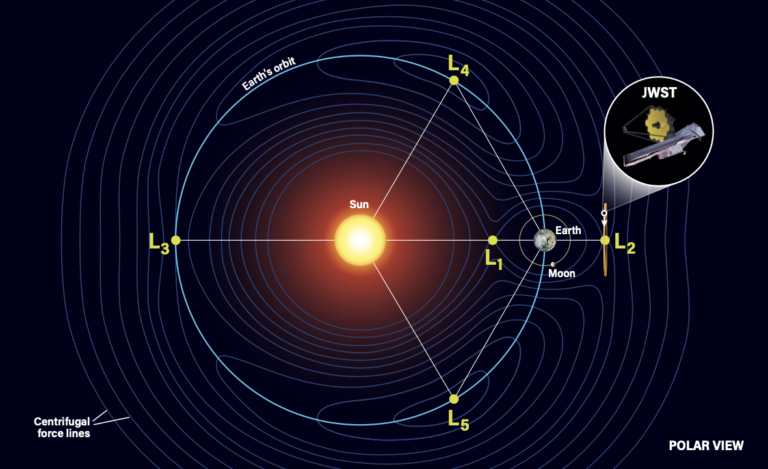

Did a comet striking one of those ice fields in North America nearly 13,000 years ago sufficiently alter climate enough to wipe out these animals and collapse the cultures that hunted them?

A new study argues that whether or not such an extraterrestrial event occurred, nothing in the archaeological record indicates that the Clovis hunters suddenly disappeared along with the animals.

Vance T. Holliday from the University of Arizona School of Anthropology and David J. Meltzer, an archaeologist at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas, studied evidence from a number of archaeological sites and concluded that it was more likely that hunting populations shifted their subsistence patterns to hunting other animals.

The controversy began several years ago when scientists cited evidence of an extraterrestrial impact 12,900 years ago somewhere around the Great Lakes that caused the Younger Dryas climate changes, the extinction of several large mammal species, and the collapse of the Paleo-Indian whose large, fluted spear points were likely designed for hunting big game animals.

Supporters of the comet theory point out that few Clovis sites continued to be occupied after their inhabitants stopped making large projectile points. Those few old Clovis sites that are reoccupied by post-Clovis people also show a significant passage of time, as much as five centuries, between them.

Holliday and Meltzer, bolstered by radiocarbon dates from more than 40 sites, counter that most prehistoric sites are kill sites where game was dispatched and butchered, and not likely to be continuously occupied. Gaps across time and the disappearance of Clovis points, they said, were more likely the result of shifting settlement patterns brought about by the nature of a nomadic existence.

“Whether or not the proposed extraterrestrial impact occurred is a matter for empirical testing in the geological record,” Holliday said. “Insofar as concerns the archaeological record, an extraterrestrial impact is an unnecessary solution for an archaeological problem that does not exist.”