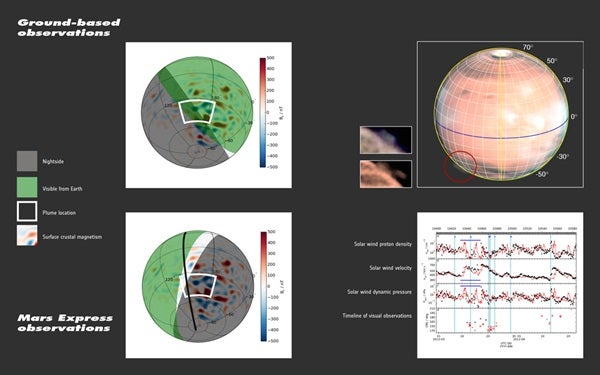

“One problem is that the plume was seen at the day–night boundary, over a region of known strong crustal magnetic fields where we know the ionosphere is generally very disturbed, so searching for ‘extra’ signatures is rather challenging.”

Furthermore, the scientists have looked at the chances of these two relatively rare events — a large and fast CME colliding with Mars, and the mysterious plume – occurring at the same time.

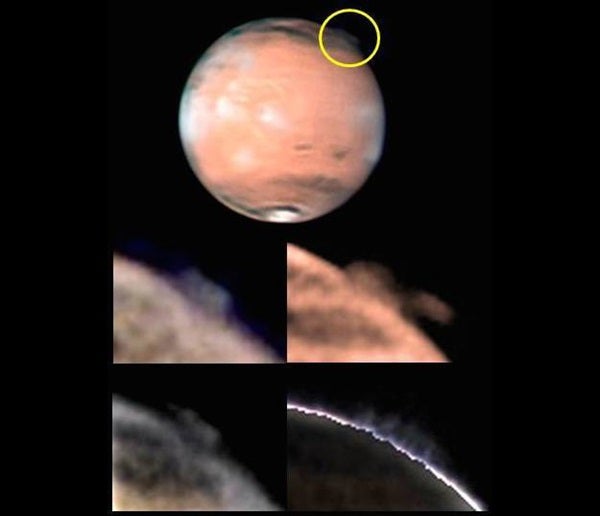

They have been searching back through the archives for similar events, but they are rare. For example, the Hubble Space Telescope observed a similar high plume in May 1997, and a CME was registered hitting Earth at the same time. Although that CME was widely studied, there is no information from Mars orbiters to judge the scale of its impact at the Red Planet.

Similarly, CMEs have been detected at Mars without any associated plume being reported, although changes in distance and visibility of Mars from Earth makes it difficult to acquire good ground-based images at all times.

“One idea is that a fast-travelling CME causes a significant perturbation in the ionosphere resulting in dust and ice grains residing at high altitudes in the upper atmosphere being pushed around by the ionospheric plasma and magnetic fields, and then lofted to even higher altitudes by electrical charging.

“This could lead to a plume effect that is significant enough to be detected from Earth by astronomers.”

“A number of processes could be responsible, but if these plumes are indeed driven by space-weather disturbances, this adds an important angle to our understanding of how Mars may have lost much of its atmosphere in the past, changing from a warm, wet world and becoming the cold, dry, dusty place it is today,” said Dmitri Titov, Mars Express project scientist.

“The plume also emphasizes the scientific potential for continuous monitoring of Mars by both orbiters and ground-based observatories. In particular, we are now going to use the webcam on Mars Express for more frequent coverage of the planet.”