A cloud of debris around a nearby planet may soon yield the first detection of an exomoon. While the planet itself won’t be crossing between Earth and its sun anytime soon, scientists realized that any moons or rings would interrupt the light coming from the star. If the planet has a large enough satellite, it could be spotted by the end of 2017.

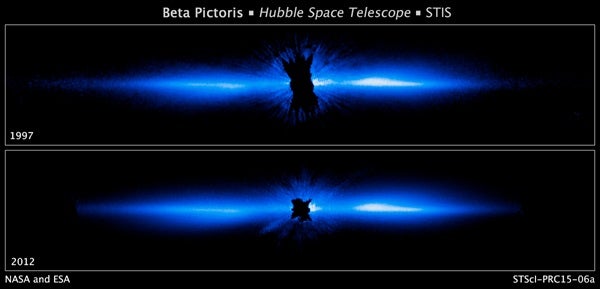

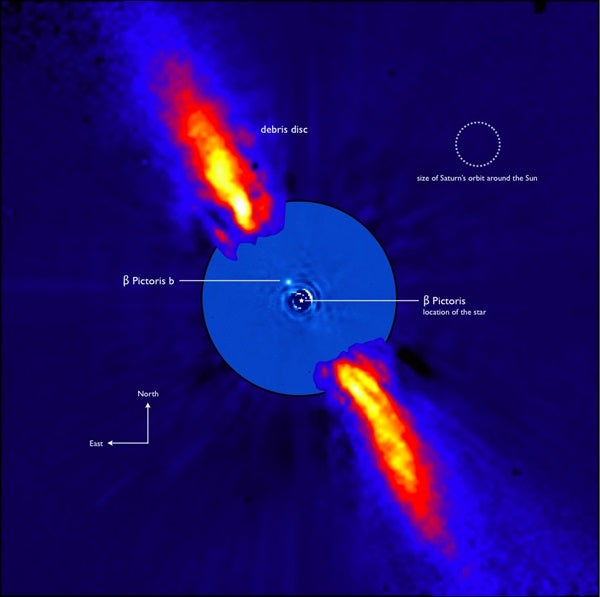

Located about 63 light-years from Earth, Beta Pictoris is a young star with a warped debris disk orbiting nearly edge-on to Earth. In 2009, scientists photographed a massive planet about 10 times as large as Jupiter orbiting the star about as far away as Saturn lies from our sun. Every 20 years, the planet, known as Beta Pictoris b (Beta Pic b), reaches its closest distance to the star, making it easier to detect any potential rings or satellites.

Instruments like NASA’s Kepler spacecraft find exoplanets by relying on transits, or worlds passing between the sun and Earth. The passage dims the light of the star, and requires multiple observations to confirm the world. These observations can help scientists determine how long it takes a planet to circle the star, and thus how wide its orbit is, but can only spot planets that move between the star and our sun. Beta Pic b was spotted using direct imaging, which essentially photographs the planet as it orbits its star. While this allows for a wider range of paths around the star, it can make it more challenging to trace the planet’s path.

Using the Gemini Planet Imager (GPI), a team of astronomers lead by Jason Wang, a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley, refined the orbit of Beta Pic b. While the planet comes tantalizingly close to passing between its star and the Earth, they found it doesn’t quite transit.

But while the planet won’t yield up its secrets through transiting, Wang and his colleagues found that any material gravitationally bound in a region known as the Hill sphere could be visible.

“Interestingly, the planet is not by itself. Generally planets have a cocoon of material around it if it’s very young, like this one,” says team member Franck Marchis, a researcher at the SETI Institute in California. Marchis presented the research last month at the Division of Planetary Sciences meeting in Pasadena, California. “Maybe in this cocoon, we have rings, information of natural satellites, the equivalent of the moons of the Jovian system.” If the moons are as large enough as Io or Ganymede, the largest of Jupiter’s satellites, they could be visible.

“This may be the first time we have the detection of an exomoon,” Marchis says.

Getting the right angle

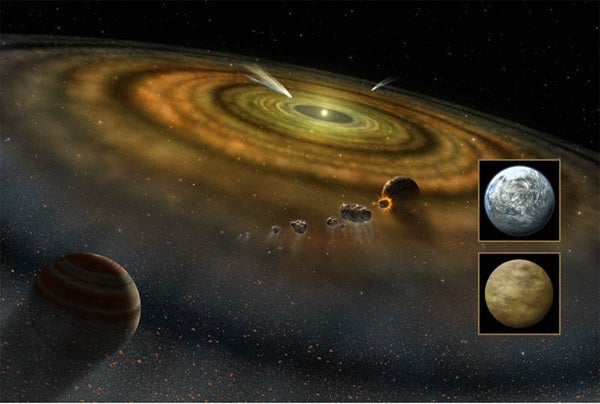

Beta Pictoris b is a large young planet. At only 24 million years old, “it’s closer in age to us than the dinosaurs,” Wang says. Young planets are more likely to still retain a cloud of debris around them leftover from their birth. Rings were spotted around a similar star, J1407, but no planet is in sight. The enormous mass of the super-Jupiter also makes it a likely candidate for hosting moons and rings.

“The transit of Beta Pic b’s Hill sphere should be our best chance in the near future to investigate young circumplanetary material,” Wang says in his paper, which was published in the Astrophysical Journal in October.

When will the window of opportunity open?

According to the new models, the cocoon of material should begin its 10 month long transit in April 2017, reaching its closest approach at the end of August. Because it will sit near the Sun in the sky, the star itself won’t be visible to most ground-based telescopes during much of the transition, though some observatories in the southern hemisphere may be able to monitor the system at the end of 2017.

While multiple telescopes will observe the system, astronomers aren’t limited to instruments on the ground. Wang intends to observe the system using NASA’s Hubble space telescope in June and August 2017.

“With these snapshots, we are hoping to search for large-scale material in the Hill sphere, such as a circumplanetary disk or large exo-ring structure,” Wang says.

Because a moon should only take two days to cross the star, spotting one during that period will be relatively hit-or-miss. If the planet boasts large rings, however, these should be visible throughout the year.

Moons in the solar system are intriguing. Wang points to the presence of volcanoes on Jupiter’s moon Io, methane lakes on Saturn’s moon Titan, and subsurface oceans on many other moons. The oceans beneath the crusts of Enceladus and Europa are especially intriguing for their potential to harbor life.

Observing the debris around Beta Pic b may also provide insights into how worlds form. “Since we can’t rewind time to look at our own solar system’s formation, we need to look at other planetary systems in the process of forming to understand how planets formed,” Wang says.

With telescopes in space and around the world all scheduled to study Beta Pic b throughout 2017, he hopes that understanding will grow a bit clearer.

“Next year is going to be the year of Beta Pic,” says Marchis.