Could people breathe on Mars? – Jack J., age 7, Alexandria, Virginia

Let’s suppose you were an astronaut who just landed on the planet Mars. What would you need to survive?

For starters, here’s a short list: Water, food, shelter – and oxygen.

Oxygen is in the air we breathe here on Earth. Plants and some kinds of bacteria provide it for us.

But oxygen is not the only gas in the Earth’s atmosphere. It’s not even the most abundant. In fact, only 21% of our air is made up of oxygen. Almost all the rest is nitrogen – about 78%.

Now you might be wondering: If there’s more nitrogen in the air, why do we breathe oxygen?

Here’s how it works: Technically, when you breathe in, you take in everything that’s in the atmosphere. But your body uses only the oxygen; you get rid of the rest when you exhale.

The air on Mars

The Martian atmosphere is thin – its volume is only 1 percent of the Earth’s atmosphere. To put it another way, there’s 99% less air on Mars than on Earth.

That’s partly because Mars is about half the size of Earth. Its gravity isn’t strong enough to keep atmospheric gases from escaping into space.

And the most abundant gas in that thin air is carbon dioxide. For people on Earth, that’s a poisonous gas at high concentrations. Fortunately, it makes up far less than 1% of our atmosphere. But on Mars, carbon dioxide is 96% of the air!

Meanwhile, Mars has almost no oxygen; it’s only one-tenth of one percent of the air, not nearly enough for humans to survive.

If you tried to breathe on the surface of Mars without a spacesuit supplying your oxygen – bad idea – you would die in an instant. You would suffocate, and because of the low atmospheric pressure, your blood would boil, both at about the same time.

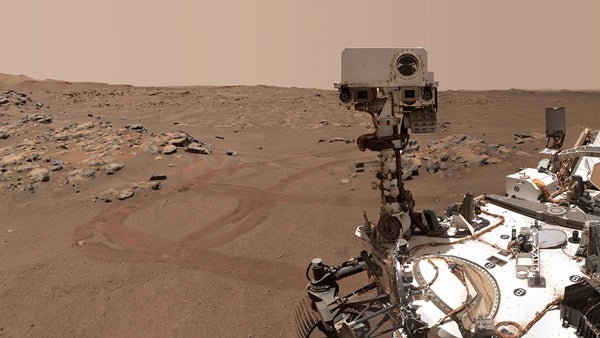

Billions of years ago, Mars’ Jezero Crater hosted an ancient lake.

Life without oxygen

So far, researchers have not found any evidence of life on Mars. But the search is just beginning; our robotic probes have barely scratched the surface.

Without question, Mars is an extreme environment. And it’s not just the air. Very little liquid water is on the Martian surface. Temperatures are incredibly cold – at night, it’s more than -100 degrees Fahrenheit (-73 degrees Celsius).

But plenty of organisms on Earth survive extreme environments. Life has been found in the Antarctic ice, at the bottom of the ocean and miles below the Earth’s surface. Many of those places have extremely hot or cold temperatures, almost no water and little to no oxygen.

And even if life no longer exists on Mars, maybe it did billions of years ago, when it had a thicker atmosphere, more oxygen, warmer temperatures and significant amounts of liquid water on the surface.

That’s one of the goals of NASA’s Mars Perseverance rover mission – to look for signs of ancient Martian life. That’s why Perseverance is searching within the Martian rocks for fossils of organisms that once lived – most likely, primitive life, like Martian microbes.

Do-it-yourself oxygen

Among the seven instruments on board the Perseverance rover is MOXIE, an incredible device that takes carbon dioxide out of the Martian atmosphere and turns it into oxygen.

If MOXIE works the way that scientists hope it will, future astronauts will not only make their own oxygen; they could use it as a component in the rocket fuel they’ll need to fly back to Earth. The more oxygen people are able to make on Mars, the less they’ll need to bring from Earth – and the easier it becomes for visitors to go there. But even with “homegrown” oxygen, astronauts will still need a spacesuit.

Right now, NASA is working on the new technologies needed to send humans to Mars. That could happen in the next decade, perhaps sometime during the late 2030s. By then, you’ll be an adult – and maybe one of the first to take a step on Mars.

See what a human mission to Mars would be like.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.![]()

Phylindia Gant, Ph.D. Student in Geological Sciences, University of Florida and Amy J. Williams, Assistant Professor of Geology, University of Florida

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.