Using new technology both at the array and in the laboratory, the scientists were able to greatly improve and speed up the process of identifying the “fingerprints” of chemicals in the cosmos, enabling studies that until now would have been either impossible or prohibitively time-consuming.

“We’ve shown that, with ALMA, we’re going to be able to do real chemical analysis of the gaseous ‘nurseries’ where new stars and planets are forming, unrestricted by many of the limitations we’ve had in the past,” said Anthony Remijan of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in Charlottesville, Virginia.

ALMA is under construction in the Atacama Desert of northern Chile, at an elevation of 16,500 feet (5 kilometers). When completed in 2013, its 66 high-precision antennas and advanced electronics will provide scientists with unprecedented capabilities to explore the universe as seen at wavelengths between longer-wavelength radio and infrared.

Those wavelengths are particularly rich in clues about the presence of specific molecules in the cosmos. More than 170 molecules, including organic ones such as sugars and alcohols, have been discovered in space. Such chemicals are common in the giant clouds of gas and dust in which new stars and planets are forming. “We know that many of the chemical precursors to life exist in these stellar nurseries even before the planets form,” said Thomas Wilson of the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, D.C.

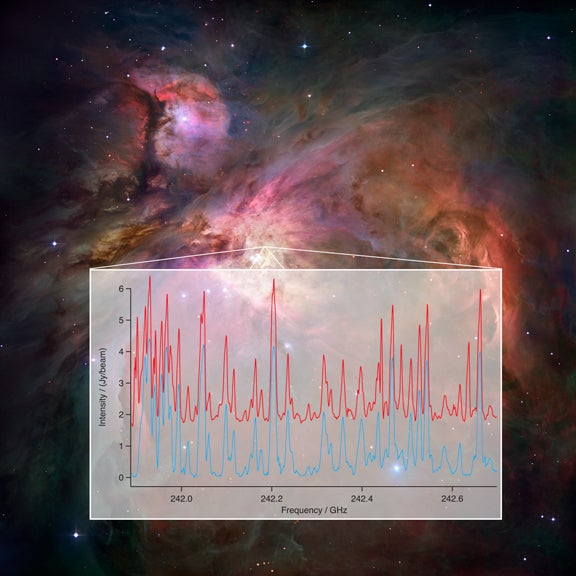

Molecules in space rotate and vibrate, and each has a particular set of rotational and vibrational conditions that are possible for it. Each time a molecule changes from one such condition to another, a specific amount of energy is either absorbed or emitted, often as radio waves at very specific wavelengths. Each molecule has a unique pattern of wavelengths that it emits or absorbs, and that pattern serves as a telltale “fingerprint” identifying the molecule.

Scientists call the individual wavelengths in such a pattern spectral lines because of their appearance in plots. A specific chemical can produce numerous spectral lines. Scientists can measure the exact wavelength of each line, but that process is quite laborious and challenging. However, without such measurements, it has been difficult to identify many lines seen in astronomical observations. Adding to the difficulty is the fact that the pattern of lines for a particular molecule changes with its temperature.

The breakthrough comes because of new technology that allows scientists to gather and analyze a broad swath of wavelengths at once, both with ALMA and in the laboratory.

“We now can take a sample of a chemical, test it in the laboratory, and get a plot of all its characteristic lines over a large range of wavelengths. We get the whole picture at once,” said Frank DeLucia of the Ohio State University. “We can then model the characteristics of all the lines of a chemical at different temperatures,” he added.

Armed with new Ohio State laboratory data for a few suspected molecules, the scientists then compared the patterns with those produced by observing the star-forming region with ALMA.

“The matchup was amazing,” said Sarah Fortman, also from Ohio State. “Spectral lines that had been unidentified for years suddenly matched our laboratory data, verified the existence of specific molecules, and gave us a new tool to attack the complex spectra from regions in our galaxy,” she added. The first tests were done with ethyl cyanide (CH3CH2CN) because its existence in space was already well-established and thus it provided a perfect test for this new method of analysis.

“In the past, there were so many unidentified lines that we called them ‘weeds,’ and they only confused our analysis,” DeLucia said. “Now those ‘weeds’ are valuable clues that can tell us not only what chemicals are present in these cosmic gas clouds, but also can give important information about the conditions in those clouds.”

“This is a new era in astrochemistry,” said Suzanna Randall of the European Southern Observatory Headquarters in Garching, Germany. “These new techniques are going to revolutionize our understanding of the fascinating nurseries where new stars and planets are being born.”

The new techniques, Remijan pointed out, also can be adapted to other telescopes, including the National Science Foundation’s giant Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia, and laboratory facilities such as those at the University of Virginia. “This is going to change the way astrochemists do business,” Remijan said.