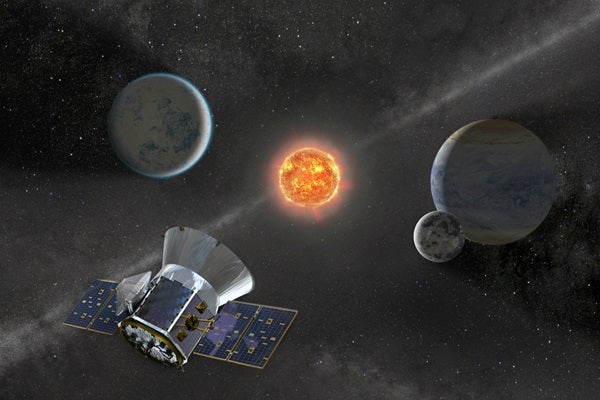

TESS detects exoplanets by monitoring the brightness of stars. Stars dim temporarily when an object passes in front of them, like the silhouette of Santa’s sleigh on the moon. The approach is called the transit method.

Last week, as part of a virtual meeting of the American Astronomical Society, researchers shared information about the exoplanets discovered by TESS. One session was dedicated to the study of the atmospheres of these alien planets.

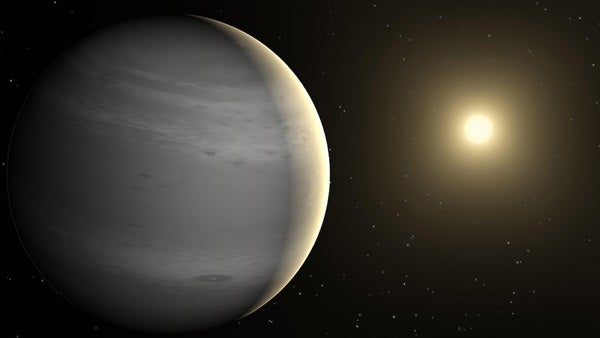

Cloudy dawns on a hot Jupiter

The exoplanet KELT-1b is a gas giant more than 27 times heavier but only 11% wider than our Jupiter. But unlike our gassy neighbor, which takes 12 years to orbit our Sun, this alien planet sprints a lap around its star about every 29 hours!

Located a mere 2 million miles away from its sun, roughly the distance between the Earth and the Moon, KELT-1b is known as a “hot Jupiter.” This category of gas giants, in contrast to the ones in our solar system, orbit very closely around their host stars.

One group of researchers sought to understand how clouds behave on these planets, and mapped out the cloud coverage of KELT-1b by observing the planet’s emitted light spectrum as it orbits around its host star.

According to Thomas Beatty from the University of Arizona in Tucson, astronomers generally believe that clouds cannot exist on the dayside of a hot Jupiter — the side where it faces the star — because they are simply too hot.

Yet, they have observed signs of clouds on the dayside of KELT-1b based on their data. They also noticed discrepancies between their observations and theoretical predictions and suggested some mechanisms to reconcile the two.

“The dayside of KELT-1b is way too hot for these clouds to exist in a steady state. So, they are only temporarily there, forming on the nightside and being transported into the dayside,” said Beatty, such that the mornings would be cloudy on the alien planet, but its sky would clear by the afternoon.

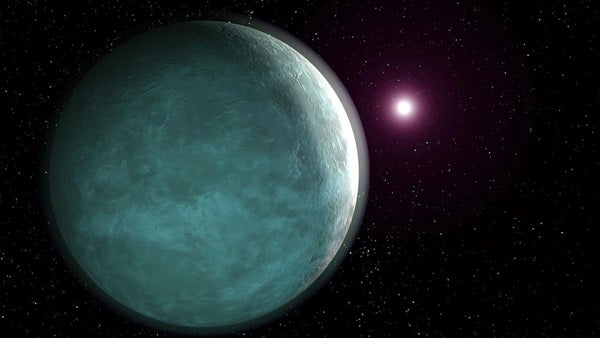

A misfit inbetweener

Hot Neptunes are rare.

“Hot” planets that orbit close to their sun are usually either gas giants, like Jupiter, or small rocky worlds, like Earth, according to Diana Dragomir from the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. Being so close to its host star, a planet either has to be massive enough to retain its thick atmosphere, or has to have lost most of its mass and be stripped to leave little more than its rocky core.

Researchers find few planets of an intermediate size. Astronomers refer to this gap as a “sub-Jovian desert” or “Neptunian desert,” due to how rare it is to find a Neptune-sized gas planet orbiting close to a star.

Dragomir presented findings on one of the very few such planets discovered to date, named LTT9779b. “Why does a planet with a core mass of 27 Earth masses not form as a [Jupiter-sized] gas giant? That is the question and the mystery for this particular planet,” said Dragomir.

To begin answering some of these questions, she shared results from the study of its atmosphere, which suggested LTT9779b is full of metal, and shiny. They were also able to estimate the dayside temperature of the planet to be around 2,300 K (a toasty 3,680 F) and the shape of its orbit, setting the stage for future studies of hot Neptunes should more of them be found.

Habitable exo-Earths?

Perhaps more tantalizing than the uninhabitable gas giants the group discussed are Earth-like exoplanets, which orbit within a star’s habitable zone.

“The habitable zone is defined by the region around the star where liquid water can exist on the planetary surface,” said Chuanfei Dong of Princeton University in New Jersey during his presentation. However, he added, existing studies mostly only consider stellar radiation and not stellar winds.

As our Sun warms us with its rays and bombards us with solar wind, the photons from the rays and the charged particles from the solar winds also partially strip away the atmosphere, via different mechanisms.

While electromagnetic radiation, as in light waves, has been the main focus when considering how a star strips a planet of its atmosphere, according to Dong, calculations showed that charged particles in solar or stellar winds also play an important role. For planets with the same size and atmospheric pressure at the same distance from the star, the ones with a stronger magnetic field are more likely to retain their atmospheres.

Hannah Diamond-Lowe from the Technical University of Denmark in Lyngby looked at an Earth-like planet orbiting around LHS 3844, a red dwarf star that’s relatively nearby in interstellar terms (about 100 light-years away). After estimating the atmospheric pressure and the radiation the planet receives from its star, the situation doesn’t look too rosy for the highly irradiated rock. Based on her team’s calculation, the planet may be shedding more than 20,000 tons of its atmosphere every second. To put that in perspective, at that rate, our atmosphere would be completely stripped away in less than 10 years.

Up until the relatively recent observations of the first exoplanets, humans have only known the eight planets orbiting our Sun. Now we know more than 4,000. Not able to cook up experimental planets in a lab, astronomers look to exoplanets as the only real-world data for understanding how different kinds of planets form and evolve in different kinds of solar systems.

As of July 2020, TESS has finished its primary mission objective and is still collecting data. The many exoplanets discovered by TESS provide prime investigation targets for the James Webb Space Telescope, which is scheduled to launch in October. The European Space Agency is also developing its own exoplanet space telescope, PLATO, which is set to launch in 2026.