Detecting exoplanets that orbit at large distances from their stars remains a challenge for planet hunters. Now, scientists at the University of Leicester in the United Kingdom have shown that emissions from the radio aurorae of planets like Jupiter should be detectable by radio telescopes such as LOFAR, which will be completed later this year.

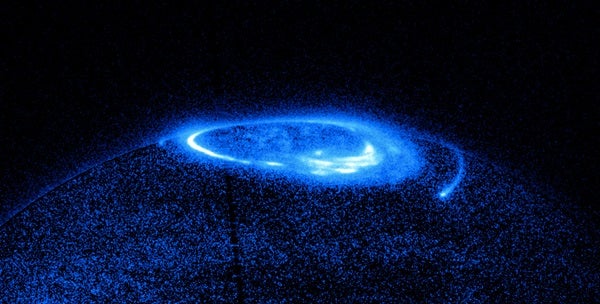

“This is the first study to predict the radio emissions by exoplanetary systems similar to those we find at Jupiter or Saturn,” said Jonathan Nichols of the University of Leicester. “At both planets, we see radio waves associated with auroras generated by interactions with ionized gas escaping from the volcanic moons Io and Enceladus. Our study shows that we could detect emissions from radio auroras from Jupiter-like systems orbiting at distances as far out as Pluto.”

Of the hundreds of exoplanets that have been detected to date, less than 10 percent orbit at distances where the outer planets in our own solar system lie. Most exoplanets have been found by the transit method, which detects a dimming in light as a planet moves in front of a star, or by looking for a wobble as a star is tugged by the gravity of an orbiting planet. With both these techniques, it is easiest to detect planets close in to the star and moving very quickly.

“Jupiter and Saturn take 12 and 30 years respectively to orbit the Sun, so you would have to be incredibly lucky or look for a very long time to spot them by a transit or a wobble,” said Nichols.

Nichols examined how the radio emissions for Jupiter-like exoplanets would be affected by the rotation rate of the planet, the rate of plasma outflow from a moon, the orbital distance of the planet, and the ultraviolet (UV) brightness of the parent star.

He found that, in many scenarios, exoplanets orbiting UV-bright stars between 1 and 50 astronomical units (AU; 1 AU is the average distance between Earth and the Sun) would generate enough radio power to be detectable from Earth. For the brightest stars and fastest-spinning planets, the emissions would be detectable from systems 150 light-years away from Earth.

“In our solar system, we have a stable system with outer gas giants and inner terrestrial planets, like Earth, where life has been able to evolve,” Nichols said. “Being able to detect Jupiter-like planets may help us find planetary systems like our own, with other planets that are capable of supporting life.”

Detecting exoplanets that orbit at large distances from their stars remains a challenge for planet hunters. Now, scientists at the University of Leicester in the United Kingdom have shown that emissions from the radio aurorae of planets like Jupiter should be detectable by radio telescopes such as LOFAR, which will be completed later this year.

“This is the first study to predict the radio emissions by exoplanetary systems similar to those we find at Jupiter or Saturn,” said Jonathan Nichols of the University of Leicester. “At both planets, we see radio waves associated with auroras generated by interactions with ionized gas escaping from the volcanic moons Io and Enceladus. Our study shows that we could detect emissions from radio auroras from Jupiter-like systems orbiting at distances as far out as Pluto.”

Of the hundreds of exoplanets that have been detected to date, less than 10 percent orbit at distances where the outer planets in our own solar system lie. Most exoplanets have been found by the transit method, which detects a dimming in light as a planet moves in front of a star, or by looking for a wobble as a star is tugged by the gravity of an orbiting planet. With both these techniques, it is easiest to detect planets close in to the star and moving very quickly.

“Jupiter and Saturn take 12 and 30 years respectively to orbit the Sun, so you would have to be incredibly lucky or look for a very long time to spot them by a transit or a wobble,” said Nichols.

Nichols examined how the radio emissions for Jupiter-like exoplanets would be affected by the rotation rate of the planet, the rate of plasma outflow from a moon, the orbital distance of the planet, and the ultraviolet (UV) brightness of the parent star.

He found that, in many scenarios, exoplanets orbiting UV-bright stars between 1 and 50 astronomical units (AU; 1 AU is the average distance between Earth and the Sun) would generate enough radio power to be detectable from Earth. For the brightest stars and fastest-spinning planets, the emissions would be detectable from systems 150 light-years away from Earth.

“In our solar system, we have a stable system with outer gas giants and inner terrestrial planets, like Earth, where life has been able to evolve,” Nichols said. “Being able to detect Jupiter-like planets may help us find planetary systems like our own, with other planets that are capable of supporting life.”