The collection of rocks that the Apollo astronauts brought back from the Moon carried with it a riddle that has puzzled scientists since the early 1970s: What produced the magnetization found in many of those rocks?

Researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) carried out the most detailed analysis of the oldest pristine rock from the Apollo collection and have solved the longstanding puzzle. Magnetic traces recorded in the rock provide strong evidence that 4.2 billion years ago the Moon had a liquid core with a dynamo, like Earth’s core today, that produced a strong magnetic field.

The Moon rock that produced the new evidence was long known to be a very special one. It is the oldest of all the Moon rocks that have not been subjected to major shocks from later impacts – something that tends to erase all evidence of earlier magnetic fields. In fact, it’s older than any known rocks from Mars or even from Earth.

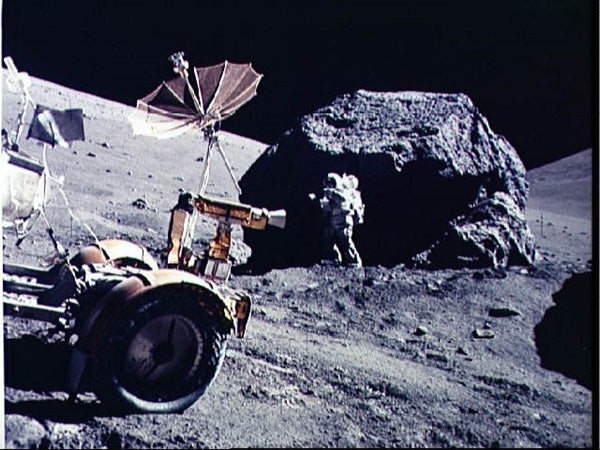

“Many people think that it’s the most interesting lunar rock,” said Ben Weiss, the Victor P. Starr assistant professor of planetary sciences in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences. The rock was collected during the last lunar landing mission, Apollo 17, by Harrison “Jack” Schmidt, the only geologist to walk on the Moon.

“It is one of the oldest and most pristine samples known,” said graduate student Ian Garrick-Bethell. “If that wasn’t enough, it is also perhaps the most beautiful lunar rock, displaying a mixture of bright green and milky white crystals.”

The team studied faint magnetic traces in a small sample of the rock in great detail. Using a commercial rock magnetometer that was specially fitted with an automated robotic system to take many readings “allowed us to make an order of magnitude more measurements than previous studies of lunar samples,” Garrick-Bethell said. “This permitted us to study the magnetization of the rock in much greater detail than previously possible.”

And the data enabled them to rule out the other possible sources of the magnetic traces, such as magnetic fields briefly generated by huge impacts on the Moon. Those magnetic fields are short lived, ranging from just seconds for small impacts up to one day for the most massive strikes. But the evidence written in the lunar rock showed it must have remained in a magnetic environment for a long period of time – millions of years – and thus the field had to have come from a long-lasting magnetic dynamo.

That’s not a new idea, but it has been “one of the most controversial issues in lunar science,” Weiss said. Until the Apollo missions, many prominent scientists were convinced that the Moon was born cold and stayed cold, never melting enough to form a liquid core. Apollo proved that there had been massive flows of lava on the Moon’s surface, but the idea that it has, or ever had, a molten core remained controversial. “People have been vociferously debating this for 30 years,” Weiss said.

The magnetic field necessary to have magnetized this rock would have been about one-fiftieth as strong as Earth’s is today. Weiss said, “This is consistent with dynamo theory,” and also fits in with the prevailing theory that the Moon was born when a Mars-sized body crashed into Earth and blasted much of its crust into space, where it clumped together to form the Moon.

The new finding underscores how much we still don’t know about our nearest neighbor in space, which will soon be visited by humans once again under current NASA plans. “While humans have visited the Moon six times, we have really only scratched the surface when it comes to our understanding of this world,” said Garick-Bethell.