According to a team of astronomers using data acquired by the Spitzer Space Telescope, our galaxy’s center harbors a bar of stars, dust, and gas measuring 28,000 light-years long — or about the same distance between our Sun and the Milky Way’s center.

While astronomers have long suspected such a structure, its presence in previous radio and infrared surveys was subtle, largely due to interference from dust in the galaxy’s plane. Now, with the help of Spitzer, astronomers have cut through the haze.

“We’re observing at wavelengths where the galaxy is more transparent, and we’re bringing tens of millions of objects into the equation,” says Robert Benjamin of the University of Wisconsin, Whitewater, and lead author of the new study.

“What’s really new is the size of this thing,” Churchwell says. “It’s huge — quite amazing a feature this dominant in our galaxy has been hidden this long.”

The astronomers say the bar extends from the galaxy’s center as two 14,000-light-year-long arms and is angled about 45° to a line connecting the Sun and the center of the Milky Way — about twice the tilt determined from previous studies.

The problem is a bit like not seeing the forest for the trees. Because our solar system lies in the galaxy’s dusty plane, we know less about the overall structure of the Milky Way than we do other galaxies.

“It has taken me 10 years to unlearn much of what we thought we knew about the Milky Way’s structure,” Benjamin says. Astronomers gleaned most of their knowledge from studies of gas clouds and star-forming regions. But dust dims distant stars, and studies of gas clouds in other galaxies show they don’t necessarily follow the same orbital paths stars do. That’s especially true around spiral arms and central bars.

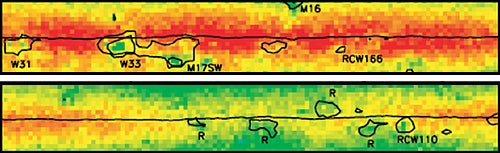

Spitzer acquired the data as part of the Galactic Legacy Infrared Mid-Plane Survey Extraordinaire, or GLIMPSE, led by Churchwell. GLIMPSE is one of six programs designed to maximize Spitzer’s long-term scientific value. The heat-sensing telescope took overlapping 1.2-second “snapshots” along the Milky Way’s equator, observing each piece of sky twice in four wavelengths with its Infrared Array Camera. GLIMPSE cataloged some 30 million infrared sources between 10° and 65° of the galaxy’s center.

“The detectors on Spitzer are so sensitive we still had saturation problems with the brightest stars, even at this short exposure,” Churchwell notes.

The astronomers noticed a discrepancy in the density of infrared sources — it was higher on one side of the Milky Way’s center than on the other. Hints of three of the Milky Way’s four expected spiral arms also appear in the survey.

“What we’re sampling is a different component of the galaxy — old, red giant stars,” Benjamin explains. More than 80 percent of GLIMPSE stars are K- and M-type giants. The GLIMPSE survey can detect orange K giants as far as 23,000 light-years away, and it can sense heat from M giants more than 160,000 light-years off — clear across the galaxy. For comparison, GLIMPSE couldn’t detect a Sun-like star beyond 3,600 light-years.

“This thing is opening up a whole range of new science,” Churchwell says. “Our survey is going to make it possible to get at the rate of star formation in the Milky Way. We’re taking the pulse of our galaxy.”

The team’s work will appear in an upcoming issue of The Astrophysical Journal.