Comets develop the spectacular long tails that they are known for by approaching the Sun. When they get too close, their icy volatile materials begin to sublimate away, carrying along clouds of dust. But this activity usually only happens relatively close to the Sun, as comets spend most of their time in the outer solar system on highly elongated orbits.

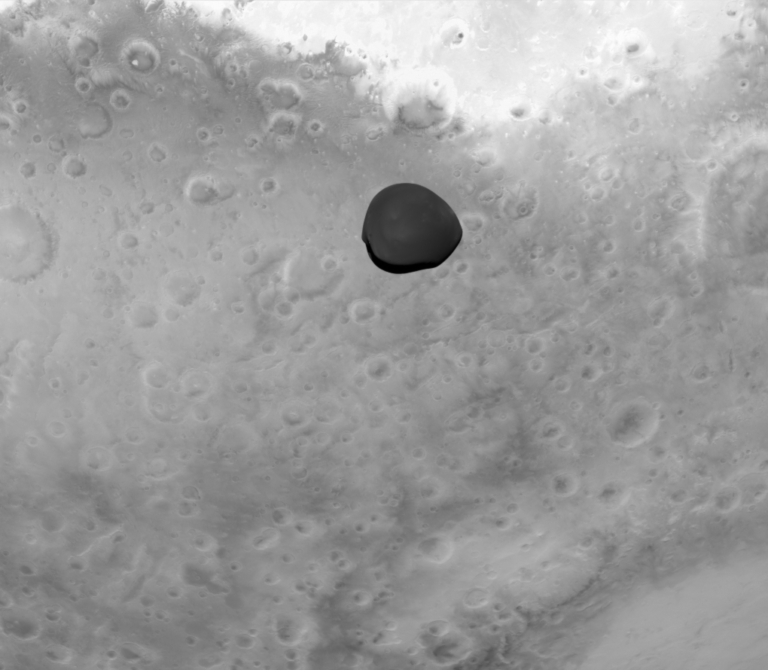

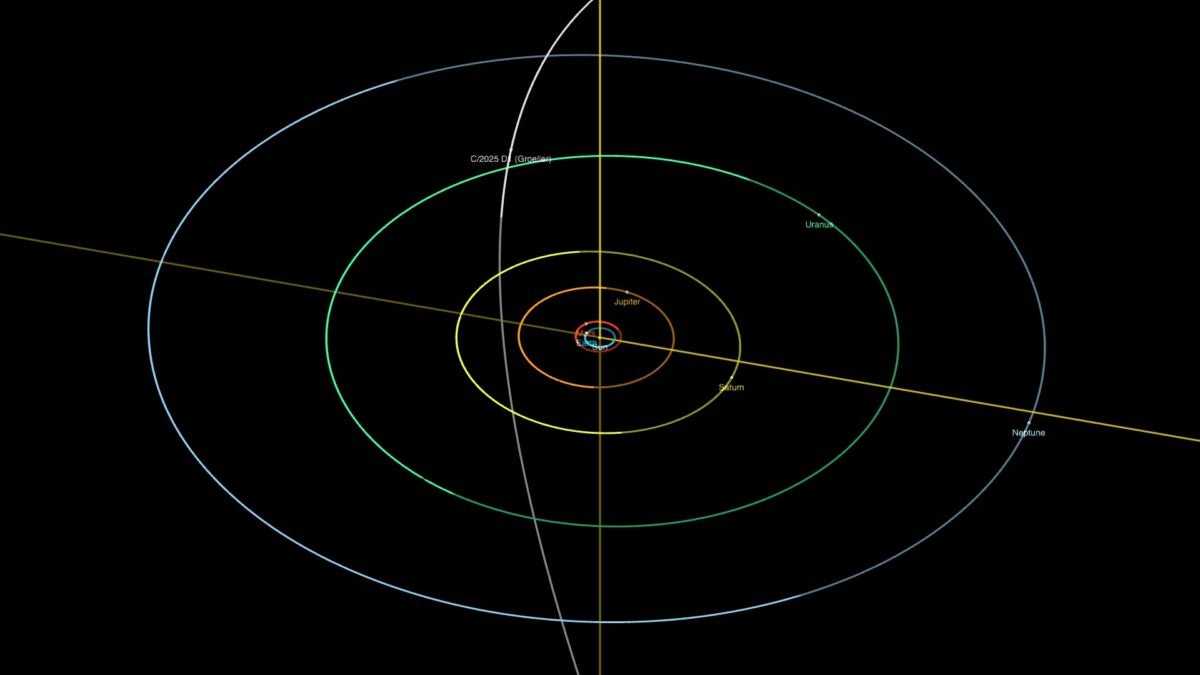

A new comet, recently discovered by Hannes Gröller of the University of Arizona, an observer with the Catalina Sky Survey, and now known as C/2025 D1 (Gröller), is smashing records. Still way out in the solar system between the orbits of Saturn and Uranus, it is nonetheless surrounded by a cloud of dust or gas, known as a coma, and even sports a broad tail. These are clear signs of cometary activity, farther from the Sun than any but a handful of previously known comets.

Highly active

Only four other comets have ever shown such activity while approaching from more than 20 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun — as far out as the orbit of Uranus. (One AU is the average Earth-Sun distance of 93 million miles [150 million kilometers]). Comet Gröller tops them all in terms of its closest approach to the Sun, or perihelion, which is the most distant of any comet yet found. This new comet, never gets closer than 14.1 AU from the Sun. The previous record holder for the most distant perihelion was 11.4 AU.

“Most comets are active around 3 to 5 AU,” Gröller tells Astronomy. That’s the distance where the Sun’s radiation can begin to trigger water-ice sublimation, which is the main driver of cometary activity, he says. Because this one is showing activity while it is so much farther out, “a different mechanism must be responsible for is activity,” he says.

The comet is on a weakly hyperbolic orbit, which means that it may escape from the solar system and never return, says Gröller.

How to find a comet

This is the fourth comet Gröller has discovered, but given its extraordinary distance, it was the most exciting find, he says. Although the Catalina Sky Survey’s main job is finding near-Earth asteroids, comets do occasionally show up in the data, and “it’s a nice perk of this job that we get a comet named after us,” he says.

The process the survey follows involves taking a series of four images of the same patch of sky and using software to pick out any objects that appear to have moved between the images. Then Gröller or one of the other observers goes through the results to pick out the ones that appear to be real objects. If it is real, then they check it against catalogs of known objects, and if it is new, they then report it to the International Astronomical Union’s Minor Planet Center, which makes the information public so that others, including amateur astronomers, can make follow-up observations to help pin down the orbit.

Sam Deen, an active amateur astronomer who specializes in tracking comets and asteroids and finding archival pre-discovery observations of them, found several such images of this comet going back to 2018, which helped to refine its orbit and determine its record-breaking perihelion distance. At that time, the comet was more than 21 AU from the Sun, beyond the orbit of Uranus. Coincidentally, the earliest of those observations came from the 90-inch Bok telescope on Kitt Peak — the same instrument that Gröller used to make the initial discovery.

“As best we can tell, these objects, if they had the same composition as normal comets, definitely should not be active” while so far from the Sun, Deen says. So, the new comet and the other four known so-called ultradistant comets must be quite different from most comets, and are possibly much older remnants of the early building blocks of the solar system.

Related: The science of comets

A strange set of comets

Man-To Hui of the Macau University of Science and Technology in China and others published a study last year in The Astronomical Journal on the four known ultradistant comets at the time, suggesting that they are all likely to be dynamically new comets — that is, ones whose orbits have never before taken them from the Oort Cloud into the inner reaches of the solar system.

In that study, they suggest that the unusual level of activity at such a great distance suggests that “these comets are conceived to be the most primitive small bodies in the solar system”and therefore “[bear] significant scientific importance.” The unexpected distant activity suggests their composition includes supervolatiles — materials such as carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide ices that have extremely low melting points and can be vaporized even by the faint sunlight at such great distances.

One of these five distant objects, Comet C/2014 UN271 (Bernardinelli-Bernstein), is a giant among comets, with a nucleus at least 75 miles (120 km) across, and was the farthest from the Sun when first discovered of any comet to date, at 29 AU. (Comet Gröller was roughly 15 AU from the Sun at discovery.) “We’re not entirely sure if it’s active because it’s an unusual sort of comet, or if it’s just because it’s so damn large that if anything at all was there [in terms of volatiles], it was going to start becoming active like this,” Deen says. “I mean, if you were to send Pluto in to 20 AU, I’m sure it would start looking like a comet, even though it’s Pluto.”

Deen adds that “we think what may potentially be happening with these comets that are active at ultradistant orbits might be that they originally formed very far from the Sun to begin with.” This would be unlike ordinary comets from the Oort Cloud, which are thought to have been ejected from the inner solar system during the early stages of planet formation. In that case, these ultradistant comets, “just formed out there, and this is genuinely their first ever time being this close to the Sun.”

If that’s the case, he says, “these things might be ultra-primordial, even beyond what normal dynamically new comets are. We could be looking at new kinds of ices that don’t really exist in this form anywhere in the rest of the solar system. . . . There’s really not many things that have never been closer [to the Sun] than [20 AU]. If they were, they would have evaporated by now.”

Within reach

Right now, the new comet glows faintly at about magnitude 20.5, Gröller says. By the time of its perihelion, on May 19, 2028, it should reach about magnitude 18.5. Even now, given sufficiently long exposure times, he says, amateurs with larger telescopes can potentially image the comet, citing a friend of his with a 14-inch telescope who has photographed it with a stack of exposures totaling about 35 minutes. As it gets brighter, it will become accessible to smaller amateur telescopes, given long enough exposure times, he says.

For those itching to give it a try, you can find more details about the comet and a link to generate an ephemeris of its position and brightness in JPL’s Small-Body Database Lookup.

Related: How to photograph comets