On Jan. 2, the Minor Planet Center at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts, announced the discovery of an unusual asteroid, designated 2018 CN41. First identified and submitted by a citizen scientist, the object’s orbit was notable: It came less than 150,000 miles (240,000 km) from Earth, closer than the orbit of the Moon. That qualified it as a near-Earth object (NEO) — one worth monitoring for its potential to someday slam into Earth.

But less than 17 hours later, the Minor Planet Center (MPC) issued an editorial notice: It was deleting 2018 CN41 from its records because, it turned out, the object was not an asteroid.

It was a car.

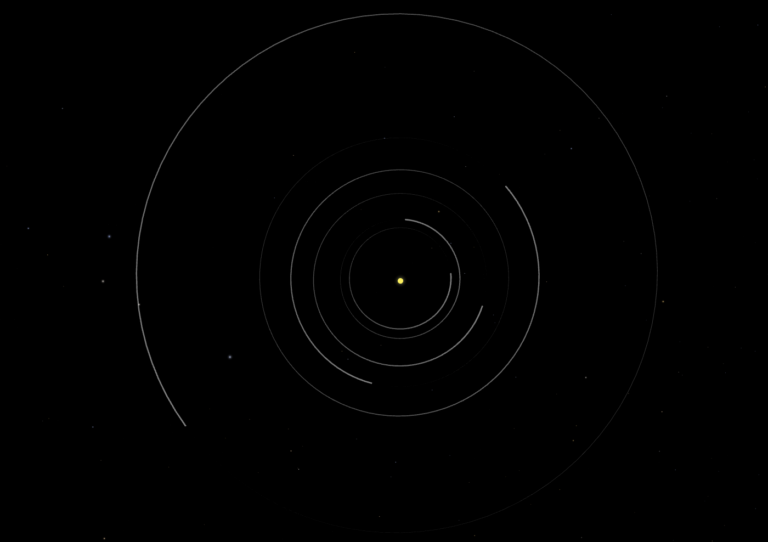

To be precise, it was Elon Musk’s Tesla Roadster mounted to a Falcon Heavy upper stage, which boosted into orbit around the Sun on Feb. 6, 2018. The car — which had been owned and driven by Musk — was a test payload for the Falcon Heavy’s first flight. At the time, it received a great deal of notoriety as the first production car to be flung into space, complete with a suited-up mannequin in the driver’s seat named Starman.

The case of mistaken identity was resolved swiftly in a collaboration between professional and amateur astronomers. But some astronomers say it is also emblematic of a growing issue: the lack of transparency from nations and companies operating craft in deep space, beyond the orbits used by most satellites. While objects in lower Earth orbits are tracked by the U.S. Space Force, deeper space remains an unregulated frontier.

If left unchecked, astronomers say the growing number of untracked objects could hinder efforts to protect Earth from potentially hazardous asteroids. They could lead to wasted observing effort and — if sufficiently numerous — even throw off statistical analyses of the threat posted by near-Earth asteroids, said Center for Astrophysics (CfA) astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell in an email to Astronomy. “Worst case, you spend a billion launching a space probe to study an asteroid and only realize it’s not an asteroid when you get there,” he said.

And it is a problem that is set to worsen as more nations and companies venture to the Moon and beyond.

A ’deplorable’ problem

The Minor Planet Center — which operates under the auspices of the International Astronomical Union — is the globally accepted authority on handling observations and reports of new asteroids, comets, and other small bodies in the solar system. Its responsibilities include identifying, designating, and computing their orbits.

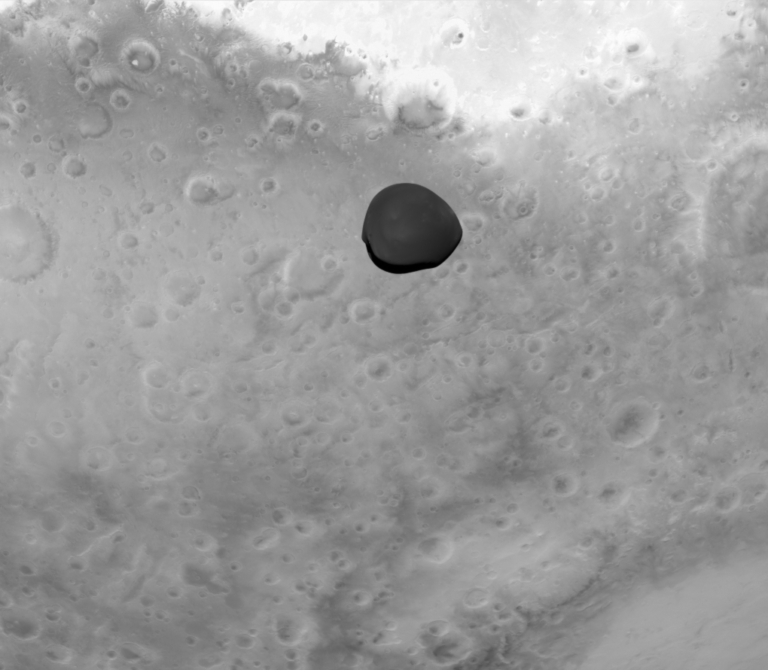

It is also no stranger to spacecraft and discarded rocket stages masquerading as asteroids. In the 2000s, NASA’s Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP), stationed in deep space around a million miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth, made it multiple times onto the MPC’s Near-Earth Object Confirmation Page (NEOCP), a list of NEOs pending confirmation. And in 2007, the MPC had to retire the asteroid designation 2007 VN84 when the object was discovered to be the Rosetta spacecraft — a high-profile European mission then performing a flyby of Earth en route to make the first ever landing on a comet.

“This incident, along with previous NEOCP postings of the WMAP spacecraft, highlights the deplorable state of availability of positional information on distant artificial objects,” the MPC fumed when it retracted 2007 VN84. “A single source for information on all distant artificial objects would be very desirable.”

That central repository has yet to manifest itself. And the rise in space launches coupled with advances in telescope surveys means the MPC is seeing an uptick in reports of artificial objects, said the center’s director, Matthew Payne, in an email.

These include defunct craft and rocket boosters as well as operational space missions. Spacecraft that are swinging by Earth for a gravity assist (like Rosetta) to more distant locales are particularly prone to being misidentified as near-Earth asteroids. So are spacecraft stationed at the L2 Lagrange point of gravitational stability beyond the Moon, like WMAP.

Over the course of 2020 through 2022, at least four spacecraft were added to the MPC’s asteroid record books — and quickly deleted. They include the European-Japanese BepiColombo mission (in transit to Mercury), NASA’s Lucy mission (headed to the Trojan asteroids in Jupiter’s orbit), the Spektr-RG X-ray observatory at L2, and what is thought to be the Centaur upper rocket stage for the 1966 Surveyor 2 lunar probe.

Uncontrolled space

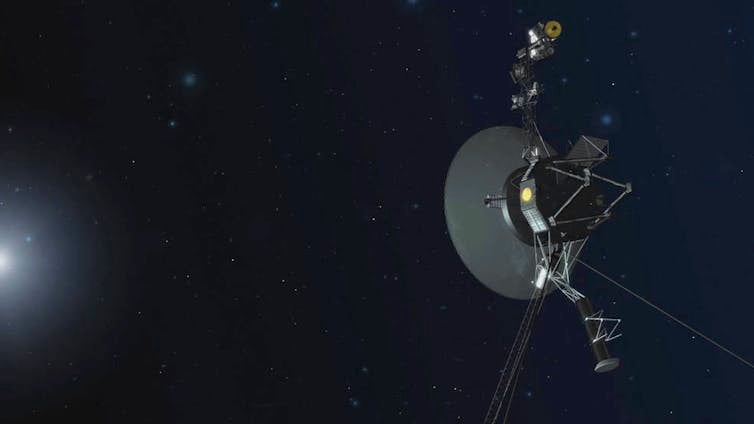

Closer to Earth, spacecraft are monitored and tracked with much more more scrutiny. Satellites in Earth orbit are regulated by national and international agencies, like the U.S. Federal Communications Commission. Companies also routinely publish orbit information for their own satellites, traditionally in a format known as two-line elements (TLEs). These data are collated by the U.S. Space Force, which also performs its own radar tracking observations and issues alerts to operators when two satellites are at risk of colliding so that they can take avoiding actions. Sharing positions and trajectories is generally in companies’ best interest as it protects their own assets from collisions and helps prevents destructive clouds of debris that could, in a worst-case scenario, render near-Earth space unusable.

But the situation is different in deep space, which is filled with a growing fleet of spacecraft at the Moon, in orbit around the Sun, and at associated Lagrange points of gravitational stability. Because of the Tesla Roadster’s fame, it happens to be included in a database maintained by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab called Horizons, which computes orbits for natural bodies in the solar system. But disclosing artificial bodies’ trajectories in deep space is not a standard industry practice.

Deep space is “largely unregulated,” McDowell told a special-session audience Jan. 14 at the American Astronomical Society’s (AAS) winter meeting in National Harbor, Maryland. “There’s no requirement to file some kind of public flight plan, no equivalent of the TLEs or the corporate data that we get for low-orbit satellites.”

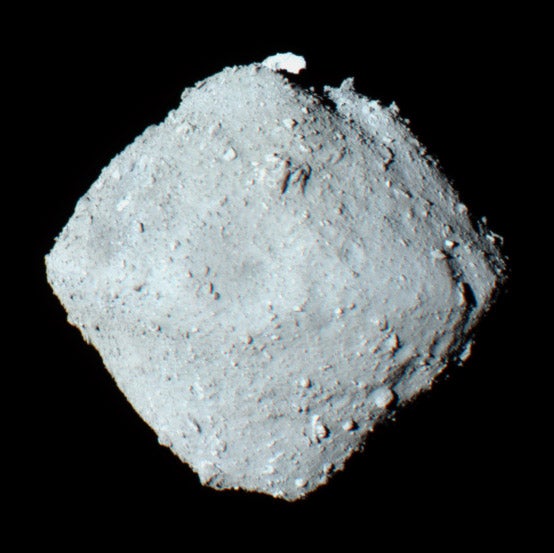

McDowell has also been critical of the asteroid mining startup AstroForge, which plans to launch two probes this year, ridesharing on the Intuitive Machines IM-2 and IM-3 missions. The craft will visit a target asteroid, prospecting for valuable platinum group metals that the company hopes to one day mine. But in order to avoid giving competitors a chance to get there first, the company did not originally intend to disclose which asteroid it is going to. “That’s kind of not OK,” said McDowell dryly at the AAS meeting.

On Jan. 21, the company’s co-founder and CEO Matt Gialich told Astronomy that Astroforge had not yet settled on a target asteroid because “as a ride share customer, we don’t control our launch date.” He added, “Jonathan McDowell is someone I respect, and I love the pushback. It’s what science is built on. I hope that images and information we deliver outweigh the perceived negatives in this case.”

Last September, the AAS raised the issue of deep-space transparency in a statement led by its Committee for the Protection of Astronomy and the Space Environment (of which McDowell is a member). It called on U.S. space operators — government agencies and non-governmental alike — to publicly report and update trajectories of deep-space objects. It also urged operators to place those data in a public repository like JPL’s Horizons, echoing the call from the MPC 17 years earlier.

On Jan. 29, in a reversal, Astroforge did disclose its target asteroid: 2022 OB5, a small near-Earth asteroid. In an interview with SpaceNews, Gialich cited the pushback from the scientific community as a factor, as well as a desire to learn more about the asteroids from observations from amateur astronomers.

At the time of publication, SpaceX had not responded to a query from Astronomy.

‘A rare confluence of factors’

The Tesla Roadster mix-up came as something of a disappointment to the Turkish amateur astronomer, who asked to be identified as “G.” He hoped he had discovered a near-Earth asteroid, not a used car from 2010 with a few billion miles on it.

He identified (the object briefly known as) 2018 CN41 with software he wrote in his spare time to parse through the MPC’s public archive of observations of objects, which anyone can peruse in search of asteroids and other small solar system bodies. His code identified several candidate objects that could be traced through multiple observations from various telescopes around the world. 2018 CN41 was one of them. It had shown up in images taken by the Catalina Sky Survey at Steward Observatory near Tucson, Arizona, and the Pan-STARRS and ATLAS surveys in Hawaii, among others.

After G. calculated an orbit to fit the observations, he saw that the object had a very small minimum orbital intersection distance (MOID) from Earth. In other words, its orbit came very close to Earth’s, making it a potential near-Earth object. “I was ecstatic and submitted the identification” to the MPC, he told Astronomy in an email. The MPC accepted the submission and notified the astronomical community in what it calls an “electronic circular,” a term of art that reflects the long legacy of observational tradition.

But after seeing the object’s trajectory plotted in 3D on the MPC’s website, he began to harbor doubts about its origins. He realized the orbit resembled that of a spacecraft traveling to Mars, using a Hohmanm transfer orbit, with the exception that it slightly overshoots Mars’ orbit. (He credits, only half-jokingly, his time playing the spaceflight simulation video game Kerbal Space Program.)

He told Astronomy:

I first went to JPL’s Small Body Database to quickly take a look at the Earth close approach dates and potential Mars close approach dates, to see if I could correlate those to a known interplanetary mission. I failed — the Falcon launch had never crossed my mind. I almost concluded it was an actual NEO and stopped looking, but I asked around on the Minor Planet Mailing List just to erase my final doubts. To my surprise, Jonathan McDowell quickly figured out it was the Falcon upper stage. Being slightly embarrassed that I might have caused unnecessary excitement (it WAS quite a low MOID), I quickly went to MPC’s help desk and let them know the NEO I just submitted was a rocket stage.

The MPC has multiple checks to flag artificial objects, said Payne, the center director, all of which broke down on the Tesla Roadster. “This case highlights a rare confluence of factors,” he said.

First, the MPC uses a routine called sat_id, written by Bill Gray and commonly used by the minor-planet community, to see if an observation of an object matches the position of a known satellite on the sky. The database of satellites it checks against is maintained by the research community of both professional and amateur astronomers.

Payne noted that when the Tesla Roadster was originally launched in 2018, the community caught it and flagged it as an artificial object, and the MPC “correctly labeled it as such without assigning a minor planet designation.”

But when subsequent observations were archived by the MPC and later identified by G., sat_id failed to locate the Roadster, said Payne. And the object was not caught upon further review because unlike most satellites, it orbits the Sun and not Earth. In addition, it is an unusual Sun-centric orbit for a spacecraft. Because it was a test flight for the Falcon Heavy, there was no destination in particular; that is why its trajectory originates near Earth but overshoots Mars’ orbit, as G. noted.

Payne agreed that a central repository, “regularly updated by national and private space agencies, would significantly enhance the identification process.” Currently, he said, the MPC is collaborating with JPL on a system to better detect artificial objects that aren’t in Earth orbit and filter them out of the MPC’s observational database.

Citizen science remains key

In one sense, this case shows the scientific process at work. Mistakes are inevitable, but quick corrections mean science is working as it should.

It also highlights the crucial role that amateur astronomers play in making discoveries — a role they have played for centuries, well before the term “citizen scientists” came into vogue. “Their involvement significantly improves the overall efficiency of object identification and contributes to the broader mission of the MPC,” said Payne.

G. is able to see the bright side of what he calls “the Tesla incident.”

“I’m still sort of disappointed it wasn’t a NEO, but it was an interesting experience to say the least,” he said. “At the very least we managed to filter out some non-minor-planet observations from [the] MPC database.”

G. continues to hunt for small bodies in the solar system on his own and in citizen science projects like Come On! Impacting ASteroids (COIAS). Developed by a team of Japanese astronomers, COIAS allows anyone to scour observations taken by the Subaru Telescope on Maunakea in Hawaii for asteroids, comets, and trans-Neptunian objects and report their measurements to the MPC.

Through COIAS, G. has been a co-discoverer of two named asteroids: 697402 Ao and 718492 Quro. The asteroids are named for one of the main characters and the author, respectively, of a slice-of-life manga named Asteroid in Love (also adapted as an anime), about two high school friends who join their school’s Earth sciences club and dream of discovering an asteroid. G. said that while he didn’t know much about it before, he “loved people who were fans of the manga get crazy about it on social media.”

Recently on COIAS, G. came across a small, “barely noticeable” speck of light moving slowly across the sky. According to his measurements, it appears to be a small body in the outer solar system that crosses Neptune’s orbit. He identified the measurements and submitted them to the MPC. On Jan. 18, he posted about it on X, the social media platform now owned by Musk, noting that the object’s orbit takes it within half an astronomical unit — the average Earth-Sun distance — from Neptune. If confirmed, the object would be a member of a dynamically intriguing subset of trans-Neptunian objects, one that has recently been studied for clues to the whereabouts of the theorized Planet Nine.

Of course, G. has his sights set on even rarer observational feats. In an email, he wrote: “I’m thinking the holy grail could be a beautiful comet, an interstellar visitor, or an alien spacecraft like in [Arthur C.] Clarke’s book Rendezvous with Rama, heh 🙂 None of that might happen, but that won’t stop me from dreaming about it.

“Realistically, at this point in time I will settle for anything that’s not a car.”

Editor’s note (Jan. 25, 2025): At the request of the amateur astronomer who identified the object, the story has been updated to remove his first initials and last name.

Editor’s note (Jan. 29, 2025): The story was updated to reflect Astroforge’s announcement of its target asteroid.