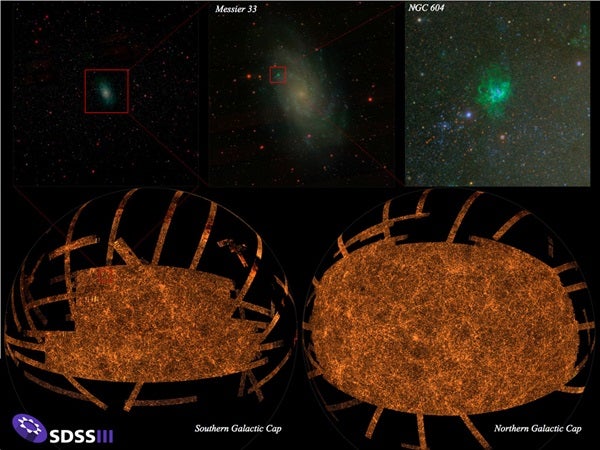

The new image is at the heart of new data being released by the SDSS-III collaboration at the 217th American Astronomical Society meeting in Seattle, Washington. This new SDSS-III data release, along with the previous data releases that it builds upon, gives astronomers the most comprehensive view of the night sky ever made. SDSS data have already been used to discover nearly half a billion astronomical objects, including asteroids, stars, galaxies, and distant quasars. The latest, most precise positions, colors, and shapes for all these objects are also being released today.

“This is one of the biggest bounties in the history of science,” said Mike Blanton from New York University. Blanton and many other scientists have been working for months preparing the release of this data. “This data will be a legacy for the ages as previous ambitious sky surveys like the Palomar Sky Survey of the 1950s are still being used today,” said Blanton. “We expect the SDSS data to have that sort of shelf life.”

The image was started in 1998 using what was then the world’s largest digital camera — a 138-megapixel imaging detector on the back of a dedicated 2.5-meter telescope at the Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico. Over the past decade, the Sloan Digital Sky Survey has scanned a third of the whole sky. Now, this imaging camera is being retired, and it will be part of the permanent collection at the Smithsonian in recognition of its contributions to astronomy.

“It’s been wonderful to see the science results that have come from this camera,” said Connie Rockosi from the University of California, Santa Cruz, who started working on the camera in the 1990s. Rockosi’s entire career so far has paralleled the history of the SDSS camera. “It’s a bittersweet feeling to see this camera retired because I’ve been working with it for nearly 20 years,” Rockosi said.

But what next? This enormous image has formed the basis for new surveys of the universe using the SDSS telescope. These surveys rely on spectra, an astronomical technique that uses instruments to spread the light from a star or galaxy into its component wavelengths. Spectra can be used to find the distances to distant galaxies, and the properties (such as temperature and chemical composition) of different types of stars and galaxies.

“We have upgraded the existing SDSS instruments, and we are using them to measure distances to over a million galaxies detected in this image,” said David Schlegel from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California. Schlegel explains that measuring distances to galaxies is more time-consuming than simply taking their pictures, but in return, it provides a detailed three-dimensional map of the galaxies’ distribution in space.

BOSS started taking data in 2009 and will continue until 2014, said Schlegel. Once finished, BOSS will be the largest 3-D map of galaxies ever made, extending the original SDSS galaxy survey to a much larger volume of the universe. The goal of BOSS is to precisely measure how dark energy has changed over the recent history of the universe. These measurements will help astronomers understand the nature of this mysterious substance. “Dark energy is the biggest conundrum facing science today,” said Schlegel, “and the SDSS continues to lead the way in trying to figure out what the heck it is!”

In addition to BOSS, the SDSS-III collaboration has been studying the properties and motions of hundreds of thousands of stars in the outer parts of our Milky Way Galaxy. The survey, known as the Sloan Extension for Galactic Understanding and Exploration (SEGUE) started several years ago, but has now been completed as part of the first year of SDSS-III.

In conjunction with the image being released today, astronomers from SEGUE are also releasing the largest map of the outer galaxy. “This map has been used to study the distribution of stars in our galaxy,” said Rockosi. “We have found many streams of stars that originally belonged to other galaxies that were torn apart by the gravity of our Milky Way. We’ve long thought that galaxies evolve by merging with others, and the SEGUE observations confirm this basic picture.”

SDSS-III is also undertaking two other surveys of our galaxy through 2014. The first, called MARVELS, will use a new instrument to repeatedly measure spectra for approximately 8,500 nearby stars like our own Sun, looking for the telltale wobbles caused by large Jupiter-like planets orbiting them. MARVELS is predicted to discover around a hundred new giant planets as well as potentially finding a similar number of brown dwarfs that are intermediate between the most massive planets and the smallest stars.

The second survey is the APO Galactic Evolution Experiment (APOGEE), which is using one of the largest infrared spectrographs ever built to undertake the first systematic study of stars in all parts of our galaxy — even stars on the other side of our galaxy beyond the central bulge. Such stars are traditionally difficult to study as their visible light is obscured by large amounts of dust in the disk of our galaxy. However, by working at longer, infrared wavelengths, APOGEE can study them in great detail, thus revealing their properties and motions to explore how the different components of our galaxy were put together.

“The SDSS-III is an amazingly diverse project built on the legacy of the original SDSS and SDSS-II surveys,” said Nichol. “This image is the culmination of decades of work by hundreds of people, and has already produced many incredible discoveries. Astronomy has a rich tradition of making all such data freely available to the public, and we hope everyone will enjoy it as much as we have.”

The new image is at the heart of new data being released by the SDSS-III collaboration at the 217th American Astronomical Society meeting in Seattle, Washington. This new SDSS-III data release, along with the previous data releases that it builds upon, gives astronomers the most comprehensive view of the night sky ever made. SDSS data have already been used to discover nearly half a billion astronomical objects, including asteroids, stars, galaxies, and distant quasars. The latest, most precise positions, colors, and shapes for all these objects are also being released today.

“This is one of the biggest bounties in the history of science,” said Mike Blanton from New York University. Blanton and many other scientists have been working for months preparing the release of this data. “This data will be a legacy for the ages as previous ambitious sky surveys like the Palomar Sky Survey of the 1950s are still being used today,” said Blanton. “We expect the SDSS data to have that sort of shelf life.”

The image was started in 1998 using what was then the world’s largest digital camera — a 138-megapixel imaging detector on the back of a dedicated 2.5-meter telescope at the Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico. Over the past decade, the Sloan Digital Sky Survey has scanned a third of the whole sky. Now, this imaging camera is being retired, and it will be part of the permanent collection at the Smithsonian in recognition of its contributions to astronomy.

“It’s been wonderful to see the science results that have come from this camera,” said Connie Rockosi from the University of California, Santa Cruz, who started working on the camera in the 1990s. Rockosi’s entire career so far has paralleled the history of the SDSS camera. “It’s a bittersweet feeling to see this camera retired because I’ve been working with it for nearly 20 years,” Rockosi said.

But what next? This enormous image has formed the basis for new surveys of the universe using the SDSS telescope. These surveys rely on spectra, an astronomical technique that uses instruments to spread the light from a star or galaxy into its component wavelengths. Spectra can be used to find the distances to distant galaxies, and the properties (such as temperature and chemical composition) of different types of stars and galaxies.

“We have upgraded the existing SDSS instruments, and we are using them to measure distances to over a million galaxies detected in this image,” said David Schlegel from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California. Schlegel explains that measuring distances to galaxies is more time-consuming than simply taking their pictures, but in return, it provides a detailed three-dimensional map of the galaxies’ distribution in space.

BOSS started taking data in 2009 and will continue until 2014, said Schlegel. Once finished, BOSS will be the largest 3-D map of galaxies ever made, extending the original SDSS galaxy survey to a much larger volume of the universe. The goal of BOSS is to precisely measure how dark energy has changed over the recent history of the universe. These measurements will help astronomers understand the nature of this mysterious substance. “Dark energy is the biggest conundrum facing science today,” said Schlegel, “and the SDSS continues to lead the way in trying to figure out what the heck it is!”

In addition to BOSS, the SDSS-III collaboration has been studying the properties and motions of hundreds of thousands of stars in the outer parts of our Milky Way Galaxy. The survey, known as the Sloan Extension for Galactic Understanding and Exploration (SEGUE) started several years ago, but has now been completed as part of the first year of SDSS-III.

In conjunction with the image being released today, astronomers from SEGUE are also releasing the largest map of the outer galaxy. “This map has been used to study the distribution of stars in our galaxy,” said Rockosi. “We have found many streams of stars that originally belonged to other galaxies that were torn apart by the gravity of our Milky Way. We’ve long thought that galaxies evolve by merging with others, and the SEGUE observations confirm this basic picture.”

SDSS-III is also undertaking two other surveys of our galaxy through 2014. The first, called MARVELS, will use a new instrument to repeatedly measure spectra for approximately 8,500 nearby stars like our own Sun, looking for the telltale wobbles caused by large Jupiter-like planets orbiting them. MARVELS is predicted to discover around a hundred new giant planets as well as potentially finding a similar number of brown dwarfs that are intermediate between the most massive planets and the smallest stars.

The second survey is the APO Galactic Evolution Experiment (APOGEE), which is using one of the largest infrared spectrographs ever built to undertake the first systematic study of stars in all parts of our galaxy — even stars on the other side of our galaxy beyond the central bulge. Such stars are traditionally difficult to study as their visible light is obscured by large amounts of dust in the disk of our galaxy. However, by working at longer, infrared wavelengths, APOGEE can study them in great detail, thus revealing their properties and motions to explore how the different components of our galaxy were put together.

“The SDSS-III is an amazingly diverse project built on the legacy of the original SDSS and SDSS-II surveys,” said Nichol. “This image is the culmination of decades of work by hundreds of people, and has already produced many incredible discoveries. Astronomy has a rich tradition of making all such data freely available to the public, and we hope everyone will enjoy it as much as we have.”