Discoveries of exoplanets in our galaxy exceed 3,700 to date, but if that’s not enough for you, astronomers are now probing outside of the Milky Way to find exoplanets in other galaxies. A group of researchers at the University of Oklahoma has just announced the discovery of a large population of free-floating planets in a galaxy 3.8 billion light-years away. Their results were published February 2 in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

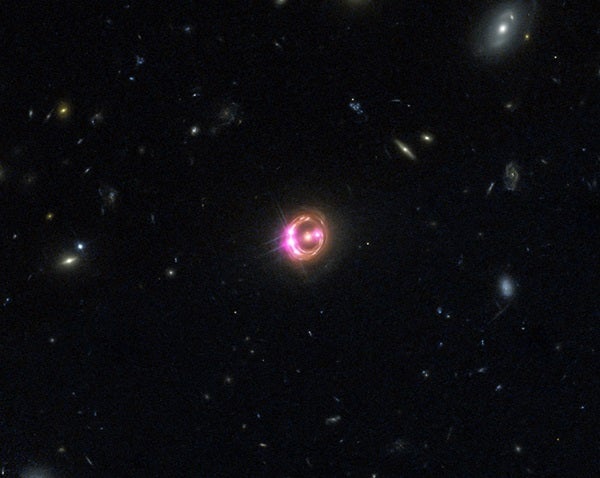

The researchers used a method known as quasar microlensing, which has traditionally been used to study the disk-like regions around supermassive black holes where material gathers as it spirals in toward the event horizon. When a distant quasar is eclipsed by a closer galaxy, the intervening galaxy will create several magnified replica images of the quasar. These replicas are further magnified by stars in the interloping galaxy to create a final super-magnified image that can be used to study the quasar in detail.

Wild planets

While studying the light emitted by the lensed quasar RXJ1131−1231 with the Chandra X-ray Observatory, the researchers noticed a particular wavelength of light emitted by iron was stronger than could be explained solely by the lensing effect of stars in the intervening galaxy. By modeling their results, the researchers concluded that the shifted energy signature was most likely caused by a huge population of planets with masses ranging from our Moon to Jupiter. The model that best matched the data found a ratio of 2,000 planets for every main sequence star in the galaxy —billions of stars. These planets are specifically “unbound” — not orbiting a star but wandering freely — as bound planets don’t have the same boosting effect seen in the data. Because the models only provided a wide range of potential planet masses, the researchers hope to identify the distribution of the sizes further with additional modeling.

Other Sightings

This isn’t the first time astronomers have claimed a discovery of an exoplanet outside our galaxy. A signature consistent with a three-Earth-mass planet was detected in a galaxy 4 billion light-years away, but the one-time chance nature of the alignment causing the microlensing meant the discovery could not be confirmed with further observations. Similarly, a different version of microlensing using a star instead of a galaxy was previously used to probe the Andromeda Galaxy. A team found deviations in the light that they believed could be caused by an exoplanet six times as massive as Jupiter, but again the detection was never confirmed.

The interloper star HIP 13044 was reported to itself host an exoplanet 25 percent larger than Jupiter, but subsequent follow-up found no evidence for the planet. Though this star is currently a part of the Milky Way, it originally came from a small galaxy that collided with the Milky Way six billion years ago.

Vagabond stars like HIP 13044 may provide our best chance for examining exoplanets from other galaxies in detail. With current telescope technology, microlensing can point to a detection in other galaxies, but it cannot fully probe the properties of these candidates. Finding relatively nearby exoplanets around stars that originated abroad, however, may help us learn more about how exoplanets form and whether there are differences between planets born in different galaxies.