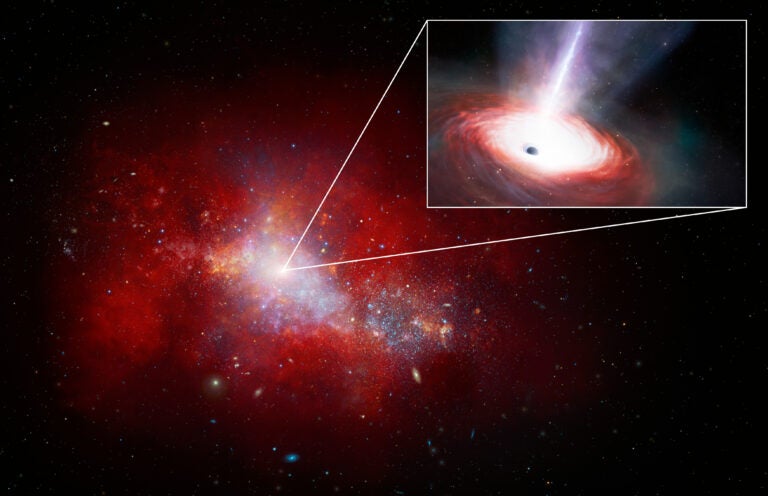

In June 2015, a black hole called V404 Cygni underwent dramatic brightening for about two weeks as it devoured material that it had stripped off an orbiting companion star.

V404 Cygni, which is about 7,800 light-years from Earth, was the first definitive black hole to be identified in our galaxy and can appear extremely bright when it is actively devouring material.

In a new study, an international team of astronomers, led by the University of Southampton, report that the black hole emitted dazzling red flashes lasting just fractions of a second as it blasted out material that it could not swallow.

The astronomers associated the red color with fast-moving jets of matter that were ejected from close to the black hole. These observations provide new insights into the formation of such jets and extreme black hole phenomena.

Lead author of the study, Poshak Gandhi from the University of Southampton’s Astronomy Group, said: “The very high speed tells us that the region where this red light is being emitted must be very compact. Piecing together clues about the color, speed, and the power of these flashes, we conclude that this light is being emitted from the base of the black hole jet. The origin of these jets is still unknown, although strong magnetic fields are suspected to play a role.

“Furthermore, these red flashes were found to be strongest at the peak of the black hole’s feeding frenzy. We speculate that when the black hole was being rapidly force-fed by its companion-orbiting star, it reacted violently by spewing out some of the material as a fast-moving jet. The duration of these flashing episodes could be related to the switching on and off of the jet, seen for the first time in detail.”

Due to the unpredictable nature and rarity of these bright black hole “outbursts,” astronomers have little time to react. For example, V404 Cygni last erupted back in 1989. V404 Cygni was exceptionally bright in June 2015 and provided an excellent opportunity for such work. In fact, this was one of the brightest black hole outbursts in recent years. But most outbursts are far dimmer, making them difficult to study.

Each flash was blindingly intense, equivalent to the power output of about 1,000 suns. And some of the flashes were shorter than 1/40th of a second — about 10 times faster than the duration of a typical blink of an eye. Such observations require novel technology, so astronomers used the ULTRACAM fast imaging camera mounted on the William Herschel Telescope in La Palma on the Canary Islands.

Vik Dhillon from the University of Sheffield and co-creator of ULTRACAM said: “ULTRACAM is unique in that it can operate at very high speed, capturing high frame-rate ‘movies’ of astronomical targets in three colors simultaneously. This allowed us to ascertain the red color of these flashes of light from V404 Cygni.”

Gandhi concluded: “The 2015 event has greatly motivated astronomers to coordinate worldwide efforts to observe future outbursts. Their short durations and strong emissions across the entire electromagnetic spectrum require close communication, sharing of data, and collaborative efforts among astronomers. These observations can be a real challenge, especially when attempting simultaneous observations from ground-based telescopes and space satellites.”

This research was a collaboration between the universities of Southampton, Sheffield and Warwick, together with international partners in Europe, USA, India, and the UAE.