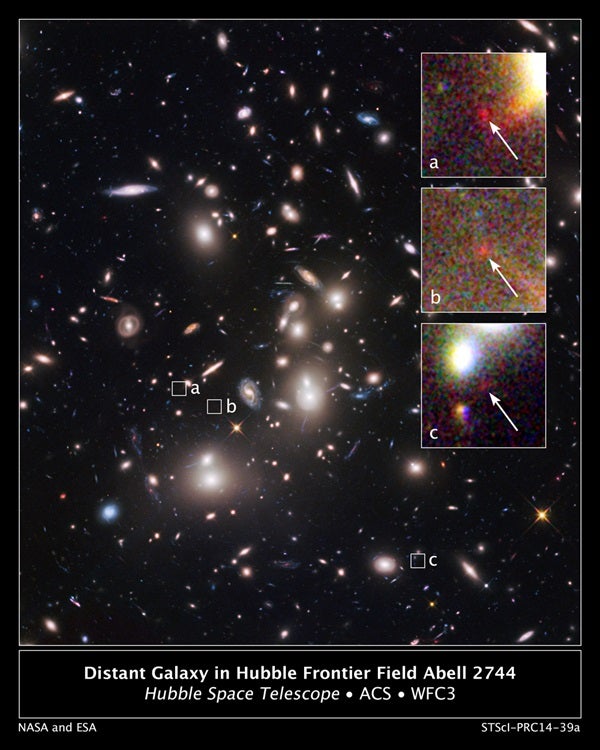

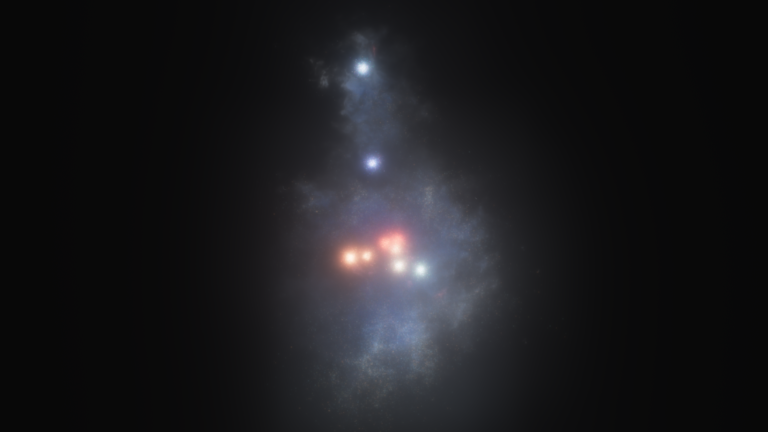

The galaxy EGS-zs8-1 was originally identified based on its particular colors in images from Hubble and Spitzer and is one of the brightest and most massive objects in the early universe. “It has already grown more than 15 percent of the mass of our own Milky Way today,” said Pascal Oesch from Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. “But it had only 670 million years to do so. The universe was still very young then.” The new distance measurement also enabled the astronomers to determine that EGS-zs8-1 was still forming stars rapidly, about 80 times faster than the Milky Way Galaxy today, which has a star formation rate of one star per year.

Measuring galaxies at these extreme distances and characterizing their properties is a main goal of astronomers over the next decade. The observations see EGS-zs8-1 at a time when the universe was undergoing important changes: The hydrogen between galaxies was transitioning from an opaque to a transparent state. “It appears that the young stars in the early galaxies like EGS-zs8-1 were the main drivers for this transition called reionization,” said Rychard Bouwens of the Leiden Observatory in the

Netherlands.

These new Hubble, Spitzer, and Keck observations together give a new glimpse into the nature of the infant universe. They confirm that massive galaxies already existed early in the history of the universe, but that their physical properties were different from galaxies seen around us today. Astronomers now have strong evidence that the peculiar colors of early galaxies seen in the Spitzer images originate from a rapid formation of massive, young stars, which interacted with the primordial gas in these galaxies.

The new observations underline the exciting discoveries that NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope will enable when it is launched in 2018. In addition to pushing the cosmic frontier to even earlier cosmic times, the Webb telescope will be able to dissect the infrared galaxy light of EGS-zs8-1 seen with the Spitzer Space Telescope and will provide astronomers with much more detailed insights into its gas properties. “Our current observations indicate that it will be easy to measure accurate distances to these distant galaxies in the future with the James Webb Space Telescope,” said Garth Illingworth of the University of California, Santa Cruz. “The result of Webb’s upcoming measurements will provide a much more complete picture of the formation of galaxies at the cosmic dawn.”