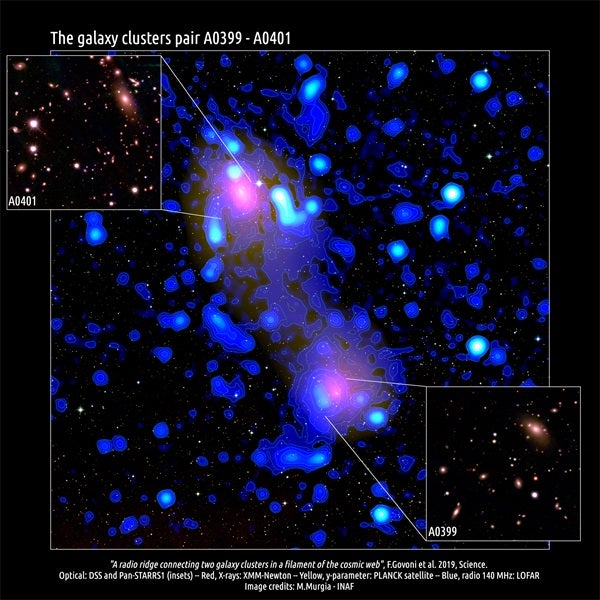

A team of astronomers led by Federica Govoni at the Italian National Institute for Astrophysics has discovered, for the first time, a “ridge” of plasma emitting radio waves and connecting two galaxy clusters in the process of merging: Abell 0399 and Abell 0401. The ridge, which is part of the cosmic web along which galaxy clusters tend to gather, stretches for about 10 million light-years and shows evidence of both a magnetic field and relativistic particles — electrons moving at close to the speed of light. Their work will be published June 7 in Science.

Following the clues

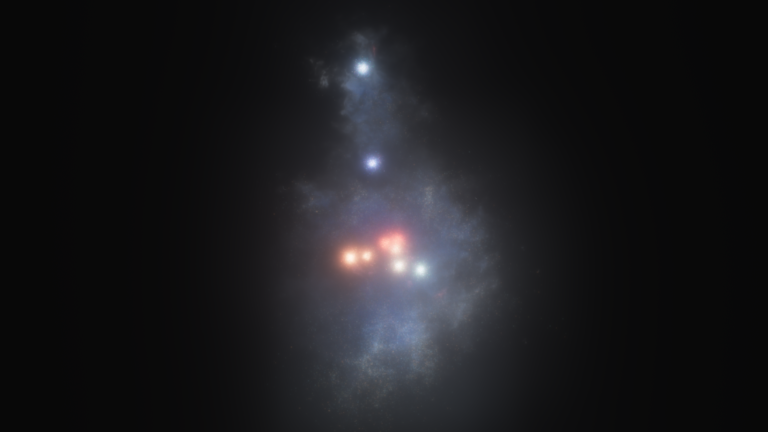

The cosmic web is exactly what it sounds like: spiderweb-like filaments of hydrogen gas stretching throughout the universe. Astronomers believe the cosmic web traces out the distribution of dark matter, which cannot be detected except by its gravitational pull, as well. Galaxy clusters tend to gather at the intersections of these filaments, which makes them extremely interesting places to study.

Govoni’s team had already found evidence of magnetic fields in the two clusters during previous work. Observations with the European Space Agency’s Plank satellite had also discovered a filament of hot plasma — part of the cosmic web — connecting the clusters as well. With those two facts in hand, Govoni’s group wondered whether magnetic fields could extend along the plasma filament, perhaps also linking the two clusters.

To investigate, the team used the Low-Frequency Array (LOFAR), a network of radio telescopes in the Netherlands. Based on their observations with LOFAR, the team spotted a “faint, diffuse, and extended radio source” between the clusters, Govoni said in a video associated with the press release. “This is direct evidence of the presence of magnetic fields and relativistic particles in the filament connecting these two systems,” she added. Based on simulations modeling their results, the team concluded the ridge has a magnetic field roughly one million times lower than Earth’s magnetic field.

Making (shock) waves

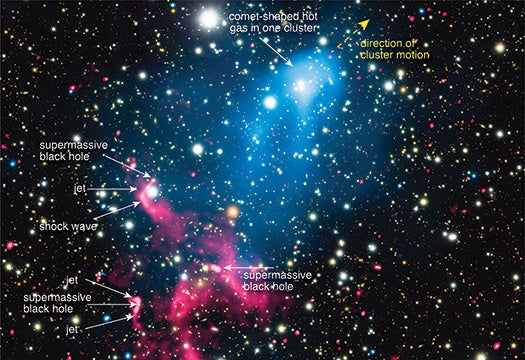

The presence of material connecting two clusters isn’t strange. But the area over which the team saw radio emission is larger than predicted, which suggests something strange is going on.

Galaxy clusters are often filled with and surrounded by fast-moving particles. In this case, Govoni’s team believes there is some process re-accelerating the already-zooming electrons in the ridge. In other words, speeding particles between the clusters are getting an extra boost from somewhere. The team believes, based on further simulations, that “something” is shock waves generated during the merging of the two clusters, which are a common occurrence and have been seen re-accelerating particles in other situations as well.

Understanding what happens when galaxy clusters merge and all the forces at play will ultimately help astronomers better understand our universe and the processes that govern it. Galaxy clusters — particularly those undergoing such mergers — are excellent natural laboratories that will continue to shed light on the way the different ingredients of our universe interact.