Before “he went to Jared,” two neutron stars collided.

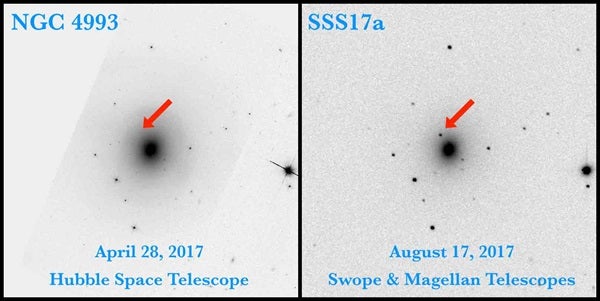

That’s what scientists learned from studying the debris fallout after a cosmic explosion called a kilonova — 1,000 times brighter than a standard nova — which appeared, and was witnessed by astronomers, in earthly skies Aug. 17.

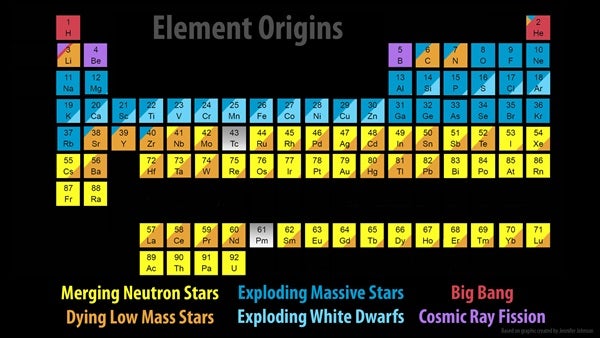

For decades, astronomers debated the origins of the heaviest elements, which includes precious metals, rare Earth elements and basically everything on the bottom rungs of the periodic table, from platinum to plutonium.

“It’s a very violent process,” says Columbia University astronomer Brian Metzger, whose team predicted neutron star mergers would create a kilonova. “The two neutron stars are moving almost at the speed of light around each other and then they slam into each other.”

Which Star Stuff?

You and I are made from pretty typical stardust — stuff that forms when large stars explode as supernovas. But supernovas make few heavy elements.

So that gold in your wedding ring, science didn’t know for sure how it came to be.

Indirect evidence pointed to colliding binary neutron stars — the dense cores of dead suns. But they don’t happen very often in any particular galaxy, and no one had ever seen such an event before.

“The question was always which one of these wins?” says University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee astronomer David Kaplan, whose team studied the August kilonova. “Is it the really common thing that makes a little? Or was it the rare thing that makes a lot?”

The chance to find out arrived this summer.

Chemical Fingerprints

A ripple in space-time — a gravitational wave — stretched and squeezed detectors the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, as well as Italy’s Virgo instrument. Electromagnetic light arrived seconds later.

Astronomers used the twin Magellen telescopes at Las Campanas Observatory in Chile to capture the chemical fingerprints, or spectra, of this cosmic collision, along with the Hubble Space Telescope. The results, published Monday in the journal Science, found signs of precious metals and radioactive waste.

“As the matter expands,” Metzger says, “there are nuclear reactions, which turn the neutrons and protons into heavier nuclei, so things like gold and silver and platinum.

All That Glitters

The merger produced somewhere between 10 and 100 Earths worth of gold — among many other heavy elements.

And based on this one observation in the relatively short period of time gravitational wave detectors were capable of seeing it, scientists can extrapolate to guess how often binary neutron stars merge—it’s about once every 10,000 years, Metzger says.

If you multiply those mergers over the Milky Way’s entire history, it indicates there should be roughly 100 million Earths worth of gold in our galaxy.

“It’s a number that comes with a factor of five uncertainty in either way,” Metzger says. “But that’s the ballpark number.”

Of course, before you pivot careers to become a space pirate and plunder the galaxy, consider that impressive gold yield is all mixed in among hundreds of billions of stars. But it could be good to keep it mind next time you’re at Tiffany & Co.

This article originally appeared on Discover. You can read more about gravitational waves in our free eBook.