Before Einstein, special relativity, and E = mc2, what was the prevailing theory on the Sun’s seemingly eternal energy?

William Fields

Dayton, Ohio

The question of what energy source powers the Sun has been around for literally centuries. During the 1800s, some thought that a constant shower of meteors onto the Sun might do the trick. Others considered (and rejected) any number of chemical combustion processes.

Independently, William Thompson (also known as Lord Kelvin) and Herman von Helmholtz came up with the idea of solar contraction in the mid-1800s. This is usually called the Kelvin-Helmholtz contraction theory. It proposed that the Sun is contracting slowly, and this contraction heats the star by converting gravitational potential energy into kinetic-thermal energy. Both performed the requisite calculation and came up with a solar lifetime between 20 million and 500 million years. However, this was in many cases much too short to be compatible with geologic evidence for the age and evolution of mountains on Earth.

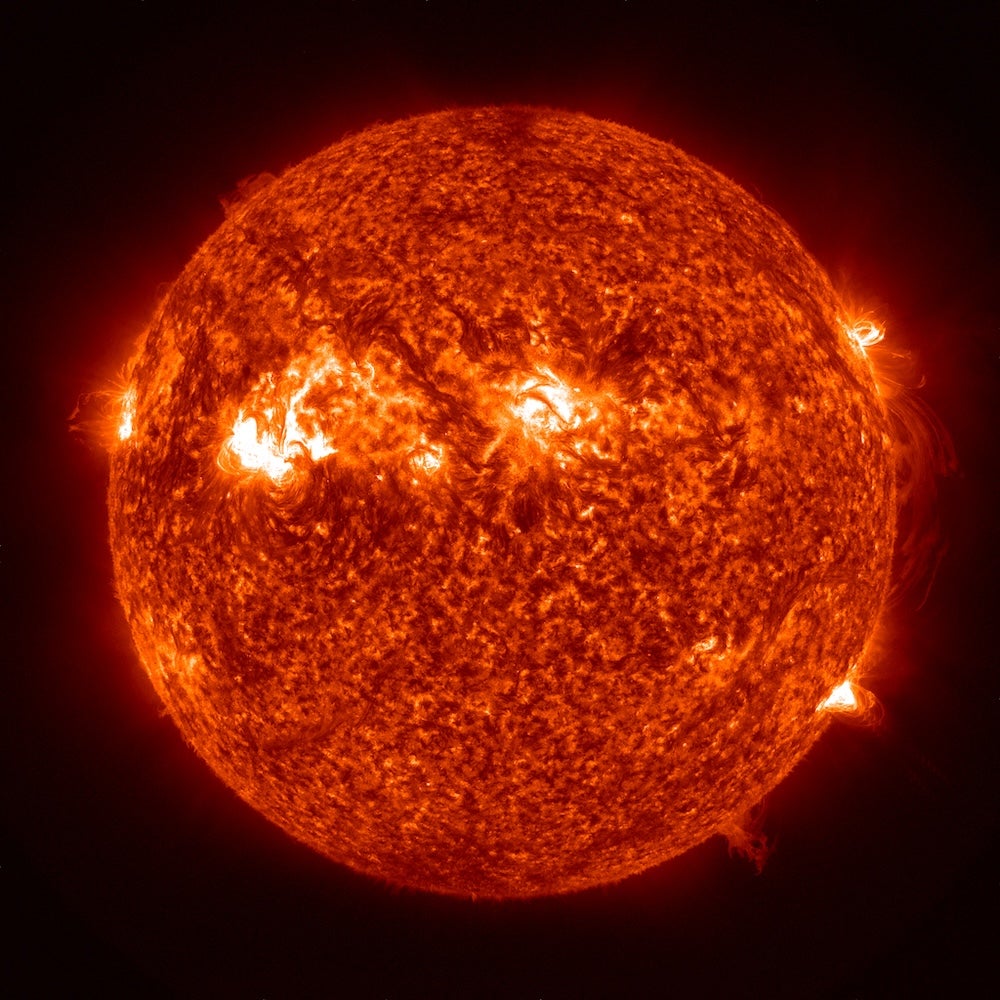

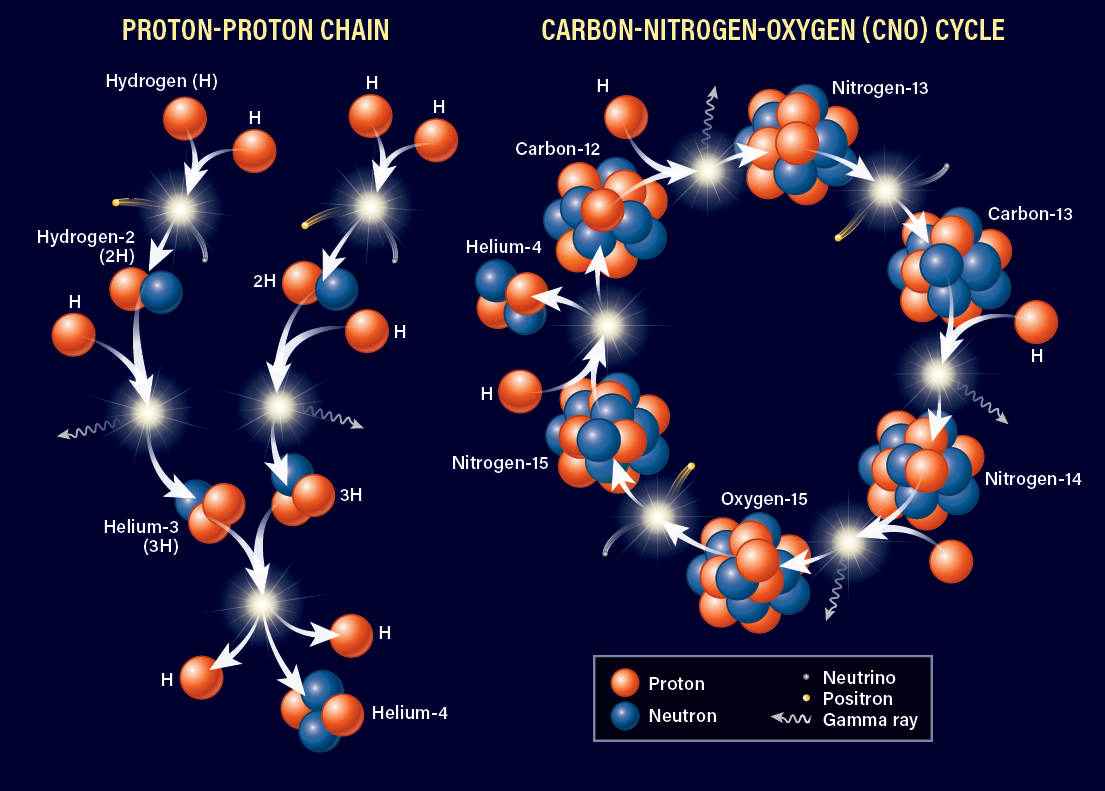

Nevertheless, it was our best guess as to the origin of solar heating, and it held sway until the dawn of the nuclear age. In the 1920s, Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington developed the concept of proton-proton fusion, which converts hydrogen into helium. Then, Hans Bethe in 1938 worked out the details of the carbon-nitrogen-oxygen (or CNO) nuclear fusion cycle, which also fuses hydrogen into helium. Both of these processes cause mass to be “lost.” Finally, Einstein’s iconic formula E = mc2 was indeed the mechanism that explained the conversion of the liberated mass into nuclear energy in the quantities needed to power the Sun and stabilize it against gravitational contraction, as we know to be the case today.

Sten Odenwald

Senior Outreach Coordinator, NASA HEAT Program, Kensington, Maryland