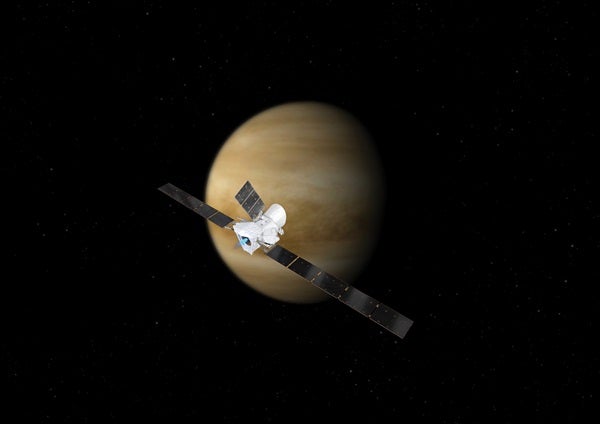

The ESA-JAXA BepiColombo spacecraft cruises by Venus in this artist’s concept. By happy coincidence, the craft will study the atmosphere of the planet one month after scientists found evidence of phosphine, a toxic gas thought to be produced only by microbial life, in Venus’ cloud tops.

ESA/ATG medialab

Just a month ago, researchers announced the presence of phosphine in the clouds of Venus — an indicator that microbial life might be present on our sister planet. And, in a happy coincidence, there’s a spacecraft scheduled to fly by this hellish world — tonight.

The European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) launched their joint BepiColombo spacecraft in October 2018 to become the third spacecraft to explore Mercury. On the way to our solar system’s innermost planet, BepiColombo will fly by Venus twice. The two encounters will utilize the planet’s gravity to help BepiColombo reach Mercury, but they now also provide a chance for scientists to study Venus’ atmosphere up close.

Want to learn more about the BepiColombo mission to Mercury? Check out our exclusive feature-length science story, straight from the pages of Astronomy magazine:

Life in the clouds

In September, an international team of astronomers using ground-based radio telescopes showed evidence that Venus’ cloud tops contain traces of phosphine. On Earth, only microbial life (and some industrial processes) create this toxic gas; there are no known non-biological processes that could make it on Venus. The observations thus raise the possibility of life on Venus. Or the gas could be due to some unknown chemical process — a less exciting but enticing alternative for scientists.

The team emphasized in a Zoom press conference that they are not claiming to have found life in Venus and point to follow-up research to answer that question definitively.

That’s where BepiColombo may come in.

Close encounter

Another spacecraft, the Japanese Venus Climate Orbiter Akatsuki, has been in orbit around Venus since 2015 to study its atmosphere. But on October 14 at 11:58 EDT, BepiColombo will fly 30 times closer closer to the planet than Akatsuki, skimming about 6,660 miles (10,720 kilometers) above the surface.

Although BepiColombo was not originally intended to search for life on Venus, several instruments on the spacecraft will be used during both flybys of Venus to study the planet. Its thermal infrared spectrometer and radiometer is capable of studying the chemical composition and cloud cover of the planet’s mid-altitude atmosphere. It’s this instrument that may also be able to verify the observations taken from Earth, although researchers aren’t sure whether it is sensitive enough to do so.

However, with this first flyby just hours away, the observational plan has already been set and cannot be altered. But the second flyby, set for next year, is more promising. This flyby will take BepiColombo even closer to Venus, a mere 342 miles (550 km) from the surface, and the team will have the time needed to revise their observations so they can better look for phosphine.

If BepiColombo is able to confirm phosphine in Venus’ atmosphere, the intrepid craft will have made scientific history before it even reaches its intended target.