Computer simulations demonstrate that a major merger between two galaxies of similar masses produces an elliptical, and this result is largely independent of whether the original galaxies are spirals or ellipticals. Beyond the simulations, though, observational evidence collected over decades also verifies this scenario.

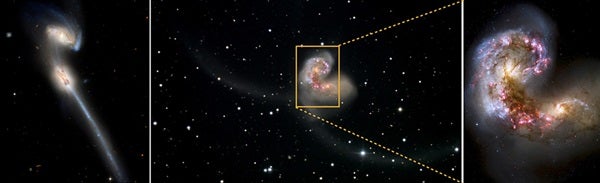

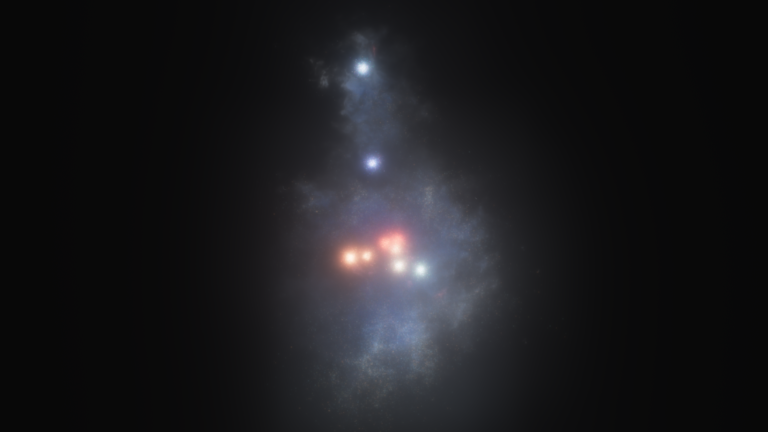

We observe strong deformation of galaxies due to close encounters or collisions — this is one of the most common ways of detecting merging systems. Tidal effects (due to the gravitational force) can form long tails of stars emanating from the interacting systems and are one of the most significant indicators of a merging system. But once the end galaxy reaches its equilibrium phase, all the collisional signs disappear and it is difficult to find out whether the galaxy had experienced a merger in the past. Deep images from some ellipticals show traces of star trails, which support the merging scenario. Studying distant galaxies to look for these signs is much more difficult because they are smaller in size and fainter than nearby galaxies.

We also use statistical methods to classify populations of disk galaxies, ellipticals, and those in between. Studying galaxies’ properties such as colors, magnitudes, and masses help us answer merger and evolution questions in this active field of research.

University of California, Riverside