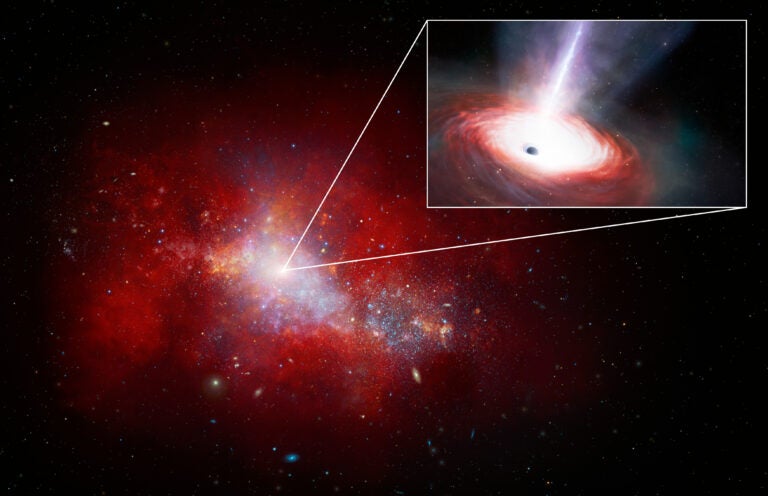

In October 2018, in a galaxy 665 million light-years away, a star made a deadly mistake: It wandered too close to a black hole, causing it to be torn to shreds.

Such stellar massacres, called Tidal Disruption Events (TDEs), aren’t anything too special to astronomers. They currently detect about 20 TDEs per year, and when the Vera Rubin Observatory begins surveying in 2024, that number is expected to jump to a many as 10,000 per year. What is unique about the October 2018 TDE, however, is what happened three years later.

In June 2021, astronomers witnessed that same black hole light up the sky again. But this time, it hadn’t swallowed anything new. The intriguing observation has been described in a study published Oct. 11 in the Astrophysical Journal.

“This caught us completely by surprise — no one has ever seen anything like this before,” said Yvette Cendes, a research associate at the Center for Astrophysics (CfA) in a press release.

When a black hole eats a star

Normally, when a star gets too close to a black hole and gets spaghettified, it violently spirals around the black hole, heating up and creating a flash that astronomers can observe.

And because black holes can be messy eaters, sometimes that stellar material gets flung back out into space again, usually clocking in at around 10 percent the speed of light as it tightly orbits the black hole. But this kind of regurgitated outflow has always been observed shortly after a TDE, fading within several months.

When this TDE, dubbed AT2018hyz was discovered, the team monitored it “in visible light for several months until it faded away, and then set it out of our minds,” said Sebastian Gomez, a postdoctoral fellow at the Space Telescope Science Institute and coauthor of the new paper. According to him, in 2018, AT2018hyz was “unremarkable.”

That all changed three years later, however, when the black hole suddenly flung out material moving at 50 percent the speed of light. “It’s as if this black hole has started abruptly burping out a bunch of material from the star it ate years ago,” Cendes said.

Not only was the black hole suddenly spewing out material, it was also one of the most radio luminous TDEs ever observed.

Delayed black hole burps

As to why the black hole seemingly rejected its meal years after devouring it, the scientists aren’t entirely sure yet. “Frankly, the trouble is we are good at saying what it isn’t, but there aren’t many theories developed yet for what happens years after a TDE to launch such an outflow!” Cendes says to Astronomy.

The researchers will next explore whether these delayed outbursts are actually commonplace — simply overlooked because scientists are not tracking TDEs long enough. And the team is already on the case.

Using the Very Large Array, the researchers searched for more late-stage TDEs. And this past weekend, they announced a preliminary detection of another delayed radio emission. The signal came from a TDE dubbed AT2019teq. This TDE originally occurred between December 2019 and May 2020, but it exhibited a delayed outflow that’s grown brighter since September 2022. Further observations, however, are needed to confirm the detection.

Should late-stage TDEs turn out to be prevalent, the discovery would offer scientists another approach to investigating the mysterious nature of black holes. “It would mean we have an entirely new regime to study black hole physics that we didn’t have before!” say Cendes. “Since we can’t test the extreme physics around them on Earth, having a new window into their behavior off Earth is always exciting.”