Key Takeaways:

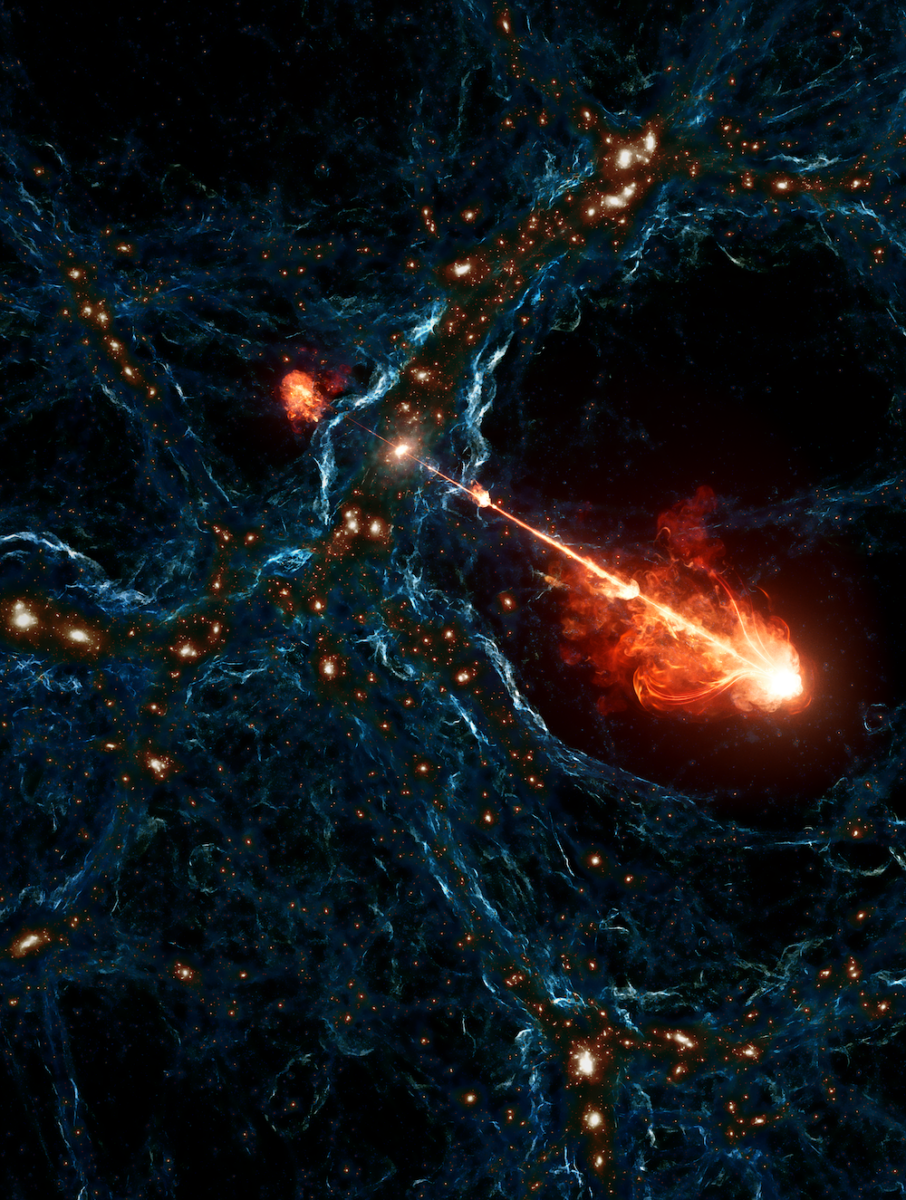

Like a dragon breathing gouts of fire, a black hole in the distant universe is spewing plumes of energy into the cosmos, forming jets that span 23 million light-years. That’s 140 times the width of the Milky Way, enough to influence the evolution of the universe at scales previously unheard of.

An international team of astronomers announced the find today in the journal Nature. They named the massive jet formation Porphyrion, after a mythological Greek giant who warred with the gods for control of the cosmos. The astronomical Porphyrion is twice as large as the previous jet formation record-holder, which was also named for a Greek giant (Alcyoneus), and found by the new study’s lead author, Martijn Oei of Caltech and Leiden University in the Netherlands, and colleagues in 2022.

The discovery of this massive outflow of energy could change astronomers’ views of how such structures affect the universe at large. By pouring many galaxies’ worth of energy into the cosmos, heating and stirring up the wispy material that lies between stars and galaxies and even clusters of galaxies, the jets can quench star formation and dictate the evolution of their cosmic neighborhoods — and the boundaries of that “neighborhood” may have just gotten a lot bigger.

Peering into the past

Porphyrion was discovered within data from a sky survey that used Europe’s LOFAR (LOw Frequency ARray) radio telescope. Radio waves are the best way to search for massive black hole jets, which form when material falls into a black hole. Most — if not all — massive galaxies contain supermassive black holes at their centers. But the black holes are usually dark and invisible, observable mostly by their gravitational puppeteering of the stars around them. But if material begins actively falling into a black hole, the turbulent swirl, like water down a drain, can shoot some of that material away again at high speeds. These are the jets that astronomers like Oei hunt.

While the LOFAR survey will eventually cover the entire Northern hemisphere, Oei and his colleagues had access to only about 15 percent of the sky. Even with that comparatively small space, the survey uncovered more than 11,000 jets that spanned more than a megaparsec (3.26 million light-years) in length. Before the survey, astronomers knew of only a few hundred.

With that much data, the team needed to outsource some of the search. Machine learning algorithms teased out some of the structures. But many of the jets were discovered by citizen scientists looking at pictures one by one. Martin Hardcastle, from the University of Hertfordshire in the UK, said during a press conference that they received most of their citizen science contributions during the early days of the pandemic. “It slowed down a bit as people went back to work,” he said. But in three years, the project received a million views.

Porphyrion was the largest system found. Once it had been identified, Oei and colleagues needed to ascertain the source of the enormous streams of energy. Using telescopes in India, Arizona, and Hawaii, they probed deeper into Porphyrion’s corner of the sky and found a galaxy roughly 70 billion solar masses (about the size of M82), viewed when the universe was a little over 6 billion years old, roughly half its current age.

A long reach — to what end?

Porphyrion’s superb length is igniting questions among astronomers. Until now, all of the enormous, megaparsec-scale jet systems have been found closer to Earth, meaning later in the universe’s 13.8-billion-year history. Astronomers saw them mostly in older, “red and dead” elliptical galaxies. While black holes can pour out enormous amounts of energy into their jets — more than 100 galaxies’ worth of stars — it takes hundreds of millions of years for those jets to extend to record-breaking lengths. Younger, star-forming galaxies were thought to be too unstable to sustain jets for so long.

But Porphyrion does exist, and at a much earlier epoch in the universe’s history, when the universe was more lively and more compact than it is today. The unceasing expansion of the universe means that 140 times the length of the Milky Way was an even more impressive distance 8 billion years ago, when the universe was smaller. Porphyrion’s long reach extends not only past its host galaxy, but two-thirds of the way into the cosmic void, the space between not just galaxies, but superclusters of galaxies. This means its reach was truly cosmological, on a scale with the largest structures in the cosmos.

And it is only the biggest of some 11,000 huge jet systems discovered (there are many tens of thousands more smaller jet systems). If jet systems like Porphyrion turn out to be common, as seems likely, then they may have had a much larger impact on the universe’s evolution than astronomers previously thought.

Astronomers have realized only in the last few decades how deeply intertwined are the evolution of a galaxy and its central black hole. When the jets from such a black hole push past the galaxy itself, their influence doesn’t stop. In addition to heating the thin material within their host and stopping star formation, they can magnetize the even gauzier material between galaxies and galaxy clusters, a phenomenon astronomers thought might be a relic of the Big Bang itself. But it is now possible that black hole jets are the architects of this process, a subtle ordering of the universe’s largest scales.

Uncovering the giants

Astronomers now have the work of finding out whether their new hypotheses hold true: Are these gargantuan systems as common as they suddenly seem? Are they having an equally large, heretofore-undiscovered influence on the evolution of the universe? How are they remaining stable for so long in such a busy time in cosmic history?

LOFAR should reveal tens of thousands more colossal jet systems as it continues to scan the skies. With thousands already identified in the first batch of data, machine learning can be used to speed up the search process on the new radio maps, providing ample fodder for these investigations.

One thing is clear: Porphyrion, a leviathan in the depths of space, is hidden no more.