Astronomers using the European Southern Observatory’s (ESPO) Very Large Telescope (VLT) have detected a stellar-mass black hole in another galaxy, farther away than any other previously known. With a mass above 15 times that of the Sun, this is also the second most massive stellar-mass black hole ever found. It is entwined with a star that will soon become a black hole itself.

The stellar-mass black holes found in the Milky Way weigh up to ten times the mass of the Sun. Outside our own galaxy, they may just be minor-league players since astronomers have found another black hole with a mass over 15 times the mass of the Sun. This is one of only three such objects found so far.

The newly announced black hole lies in a spiral galaxy called NGC 300, 6 million light-years from Earth. “This is the most distant stellar-mass black hole ever weighed, and it’s the first one we’ve seen outside our own galactic neighborhood, the Local Group,” said Paul Crowthers, professor of astrophysics at the University of Sheffield in the United Kingdom. The black hole’s curious partner is a Wolf-Rayet star that also has a mass of about twenty times as much as the Sun. Wolf-Rayet stars are near the end of their lives and expel most of their outer layers into their surroundings before exploding as supernovae, with their cores imploding to form black holes.

In 2007, an X-ray instrument aboard NASA’s Swift observatory scrutinized the surroundings of the brightest X-ray source in NGC 300 discovered earlier with the European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton X-ray observatory. “We recorded periodic, extremely intense X-ray emission, a clue that a black hole might be lurking in the area,” said team member Stefania Carpano from the European Space Agency (ESA).

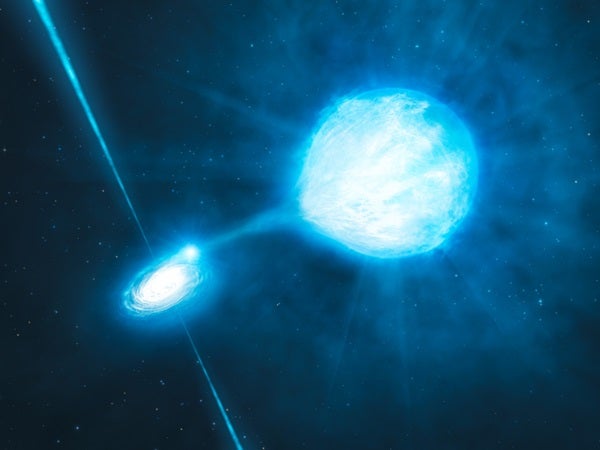

Thanks to new observations performed with the FORS2 instrument mounted on ESO’s VLT, astronomers have confirmed their earlier hunch. The new data show that the black hole and the Wolf-Rayet star dance around each other in a period of about 32 hours. The astronomers also found that the black hole is stripping matter away from the star as they orbit each other.

“This is indeed a very ‘intimate’ couple,” said collaborator Robin Barnard. “How such a tightly bound system has been formed is still a mystery.” Only one other system of this type has previously been seen, but other systems comprising a black hole and a companion star are not unknown to astronomers. Based on these systems, the astronomers see a connection between black hole mass and galactic chemistry. “We have noticed that the most massive black holes tend to be found in smaller galaxies that contain less heavy chemical elements,” said Crowther. “Bigger galaxies that are richer in heavy elements, such as the Milky Way, only succeed in producing black holes with smaller masses.” Astronomers believe that a higher concentration of heavy chemical elements influences how a massive star evolves, increasing how much matter it sheds, resulting in a smaller black hole when the remnant finally collapses.

In less than a million years, it will be the Wolf-Rayet star’s turn to go supernova and become a black hole. “If the system survives this second explosion, the two black holes will merge, emitting copious amounts of energy in the form of gravitational waves as they combine,” said Crowther. However, it will take a few billion years until the actual merger, far longer than human timescales. “Our study does, however, show that such systems might exist, and those that have already evolved into a binary black hole might be detected by probes of gravitational waves, such as LIGO or Virgo.”