The discovery in galaxy NGC 4845, 47 million light-years away, was made by the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Integral space observatory, with follow-up observations from ESA’s XMM-Newton, NASA’s Swift, and Japan’s MAXI X-ray monitor on the International Space Station.

Astronomers were using Integral to study a different galaxy when they noticed a bright X-ray flare coming from another location in the same wide field of view. Using XMM-Newton, the origin was confirmed as NGC 4845, a galaxy never before detected at high energies.

Scientists used XMM-Newton, along with Swift and MAXI, to trace the emission from its maximum in January 2011, when the galaxy brightened by a factor of a thousand, and then as it subsided over the course of the year.

“The observation was completely unexpected from a galaxy that has been quiet for at least 20–30 years,” said Marek Nikolajuk of the University of Bialystok in Poland.

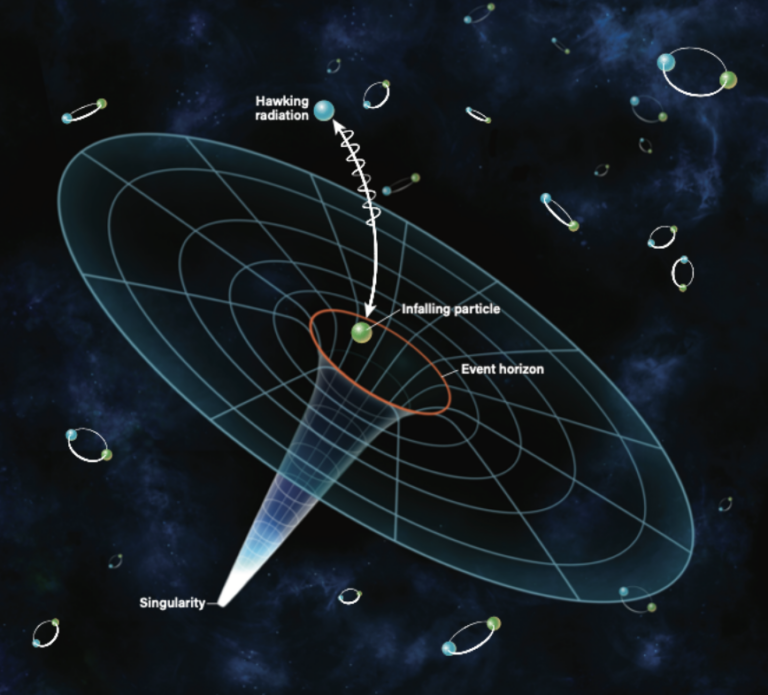

By analyzing the characteristics of the flare, the astronomers could determine that the emission came from a halo of material around the galaxy’s central black hole as it tore apart and fed on an object of 14 to 30 Jupiter masses. This size range corresponds to brown dwarfs, substellar objects that are not massive enough to fuse hydrogen in their core and ignite as stars.

However, the scientists note that it could have had an even lower mass, just a few times that of Jupiter, placing it in the range of gas-giant planets.

Recent studies have suggested that free-floating planetary-mass objects of this kind may occur in large numbers in galaxies, ejected from their parent solar systems by gravitational interactions.

The black hole in the center of NGC 4845 is estimated to have a mass of around 300,000 times that of our Sun. It also likes to play with its food: The way the emission brightened and decayed shows there was a delay of two to three months between the object being disrupted and the heating of the debris in the vicinity of the black hole.

“This is the first time where we have seen the disruption of a substellar object by a black hole,” said Roland Walter of the Observatory of Geneva in Switzerland.

“We estimate that only its external layers were eaten by the black hole, amounting to about 10 percent of the object’s total mass, and that a denser core has been left orbiting the black hole.”

While there are no brown dwarfs or planets on the menu for the Milky Way this time, a compact cloud of gas amounting to just a few Earth masses has been seen spiraling toward the black hole and is predicted to meet its fate soon.

Along with the object seen being eaten by the black hole in NGC 4845, these events will tell astronomers more about what happens to the demise of different types of objects as they encounter black holes of varying sizes.

“Estimates are that events like these may be detectable every few years in galaxies around us, and if we spot them, Integral, along with other high-energy space observatories, will be able to watch them play out just as it did with NGC 4845,” said Christoph Winkler from ESA.