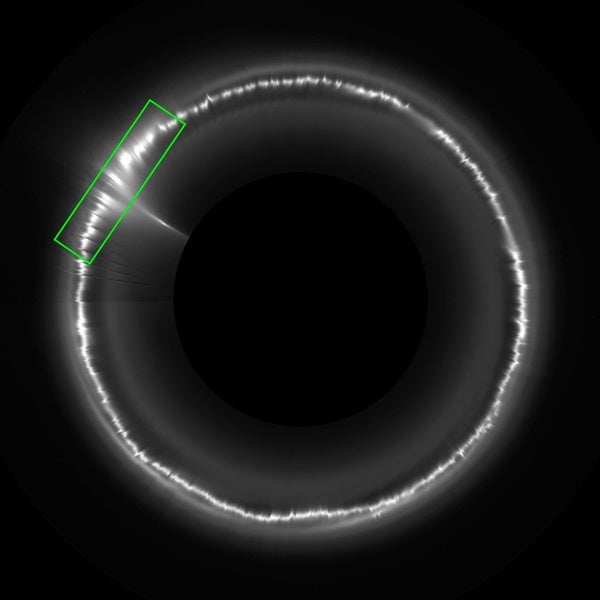

Case in point: Saturn’s narrow, chaotic, and clumpy F ring. A recent NASA-funded study compared the F ring’s appearance in six years of observations by the Cassini mission to its appearance during the Saturn flybys of NASA’s Voyager mission, 30 years earlier. The study team found that, while the overall number of clumps in the F ring remained the same, the number of exceptionally bright clumps of material plummeted during that time. While the Voyagers saw two or three bright clumps in any given observation, Cassini spied only two of the features during a six-year period. What physical processes, they wondered, could cause only the brightest of these features to decline sharply?

While a variety of features in Saturn’s many rings display marked changes over multiple years, the F ring seems to change on a scale of days, and even hours. Trying to work out what is responsible for the ring’s tumultuous behavior is a major goal for ring scientists working on Cassini.

“Saturn’s F ring looks fundamentally different from the time of Voyager to the Cassini era,” said Robert French of the SETI Institute in Mountain View, California. “It makes for an irresistible mystery for us to investigate.”

The researchers hypothesize that the brightest clumps in the F ring are caused by repeated impacts into its core by small moonlets up to about 3 miles (5 kilometers) wide, whose paths around Saturn lie close to the ring and cross into it every orbit. They propose that the diminishing number of bright clumps results from a drop in the number of these little moonlets between the Voyager and Cassini eras.

As for what might have caused the moonlets to become scarce, the team has a suspect: Saturn’s moon Prometheus. The F ring encircles the planet at a special location, near a place called the Roche limit — get any closer to Saturn than this, and tidal forces from the planet’s gravity tear apart smaller bodies. “Material at this distance from Saturn can’t decide whether it wants to remain as a ring or coalesce to form a moon,” French said. Prometheus orbits just inside the F ring and adds to the pandemonium by stirring up the ring particles, sometimes leading to the creation of moonlets and sometimes leading to their destruction.

Every 17 years, the orbit of Prometheus aligns with the orbit of the F ring in such a way that its influence is particularly strong. The study team thinks this periodic alignment might spur the creation of many new moonlets. The moonlets would then crash repeatedly through the F ring, like cars in a Hollywood high-speed chase, creating bright clumps as they smash across lanes of ring material. Fewer clumps would be created as time goes by because the moonlets themselves are eventually destroyed by all the crashes.

As with any good scientific hypothesis, the researchers offer a way to test their ideas. It happens that the Voyager encounters with Saturn occurred a few years after the 1975 alignment between Prometheus and the F ring, and Cassini was present for the 2009 alignment. If the moon’s periodic influence is indeed responsible for creating new moonlets, then the researchers expect that Cassini would see the F ring return to a Voyager-like number of bright clumps in the next couple of years.

“Cassini’s continued presence at Saturn gives us an interesting opportunity to test this prediction,” said Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, who was not involved in the study. “Whatever the result, we’re certain to learn something valuable about how rings, as well as planets and moons, form and evolve.”