An international team led by French and Canadian astronomers has just discovered the coldest brown dwarf ever observed. Their results will soon be published in Astronomy & Astrophysics. This new finding was made possible by the performance of worldwide telescopes: Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope (CFHT) and Gemini North Telescope, both located in Hawaii, and the ESO/NTT located in Chile.

The brown dwarf is named CFBDS J005910.83-011401.3 (it will be called CFBDS0059 in the following). Its temperature is about 350° C and its mass about 15-30 times the mass of Jupiter, the largest planet of our solar system. Located about 40 light-years from our solar system, it is an isolated object, meaning that it doesn’t orbit another star.

Brown dwarfs are intermediate bodies between stars and giant planets (like Jupiter). The mass of brown dwarfs is usually less than 70 Jupiter masses. Because of their low mass, their central temperature is not high enough to maintain thermonuclear fusion reactions over a long time. In contrast to a star like our Sun, which spends most of its lifetime burning hydrogen hence keeping a constant internal temperature, a brown dwarf spends its lifetime getting colder and colder after having been formed.

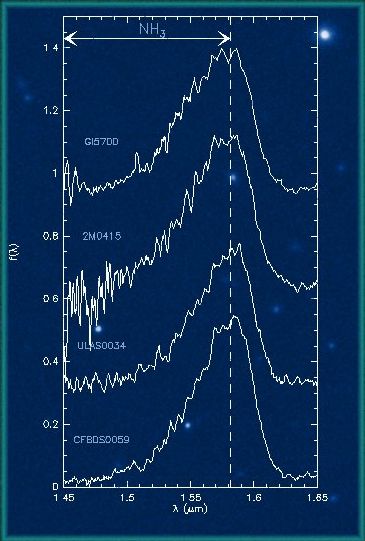

To date, two classes of brown dwarfs have been known: the L dwarfs (temperature of 1200-2000° C), which have clouds of dust and aerosols in their high atmosphere, and the T dwarfs (temperature lower than 1200° C), which have a very different spectrum because of methane forming in their atmosphere. Because it contains ammonia and has a much lower temperature than do L and T dwarfs, CFBDS0059 might be the prototype of a new class of brown dwarfs to be called the Y dwarfs. This new class would become the coldest stellar objects, hence the missing link toward giant planets. Astronomers could then fill in the domain from the hottest stars to the giant planets of less than -100° C.

This discovery also has important implications in the study of extrasolar planets. The atmosphere of brown dwarfs looks very much like that of giant planets, therefore the same models are used to reproduce their physical conditions. Such modeling requires to be constrained with observations. Observing the atmospheres of extrasolar planets is indeed very hard because the light from the planets is embedded in the much stronger light from their parent star. Because brown dwarfs are isolated bodies, they are much easier to observe. Thus, looking to brown dwarfs with a temperature close to that of the giant planets will help in constraining the models of extrasolar planets’ atmospheres.