A new movie and images showing Saturn’s shimmering aurora over a 2-day period are helping scientists understand what drives some of the solar system’s most impressive light shows.

The movie and images are part of a new study that, for the first time, extracts auroral information from the entire catalog of Saturn images taken by the visual and infrared mapping spectrometer instrument (VIMS) aboard NASA’s Cassini spacecraft. These images and preliminary results are being presented by Tom Stallard, lead scientist on a joint VIMS and Cassini magnetometer collaboration, at the European Planetary Science Congress in Rome, Italy, Friday, September 24.

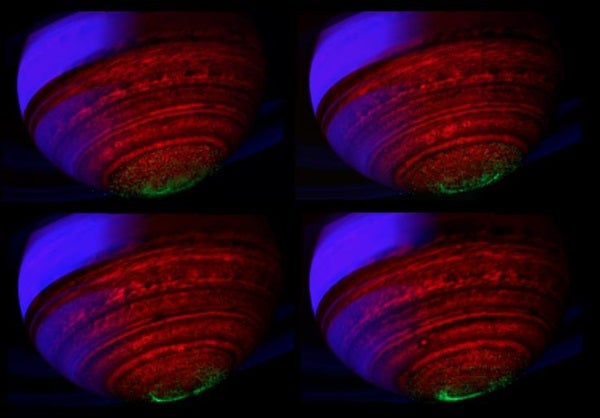

In the movie, the aurora phenomenon clearly varies significantly over the course of a saturnian day, which lasts around 10 hours and 47 minutes. On the noon and midnight sides (left and right sides of the images, respectively), the aurora brightens significantly for periods of several hours, suggesting the brightening is connected with the angle of the Sun. Other features appear to rotate with the planet, reappearing at the same time and the same place on the second day, suggesting that these are directly controlled by the orientation of Saturn’s magnetic field.

“Saturn’s auroras are very complex and we are only just beginning to understand all the factors involved,” Stallard said. “This study will provide a broader view of the wide variety of different auroral features that can be seen, and will allow us to better understand what controls these changes in appearance.”

Aurorae on Saturn occur in a process similar to Earth’s northern and southern lights. Saturn’s magnetic field channels particles from the solar wind toward the planet’s poles, where they interact with electrically charged gas (plasma) in the upper atmosphere and emit light. At Saturn, however, auroral features can also be the result of electromagnetic waves generated when the planet’s moons move through the plasma that fills Saturn’s magnetosphere.

However, VIMS observations of numerous other scientific targets also include auroral information. Sometimes the aurora is clearly visible, but sometimes Stallard and colleagues add multiple images together to produce a signal. This wide set of observations allows Cassini scientists to understand the aurora in general, rather than the beautiful specific cases that dedicated auroral observations allow, Stallard said.

Stallard and his colleagues have investigated about 1,000 images from the 7,000 that VIMS has taken to date of Saturn’s auroral region.

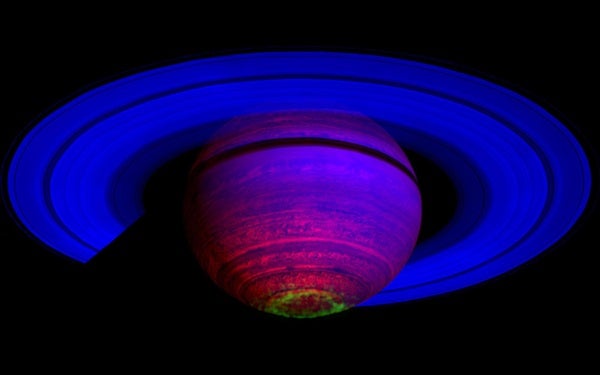

The new, false-color images show Saturn’s aurora glowing in green around the planet’s south pole. The auroral information in the two images was extracted from VIMS data taken on May 24, 2007 (set of four), and November 1, 2008 (image with rings). The video covers about 20 Earth hours of VIMS observations, from September 22 and 23, 2007.

“Detailed studies like this of Saturn’s aurora help us understand how they are generated on Earth and the nature of the interactions between the magnetosphere and the uppermost regions of Saturn’s atmosphere,” said Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist, based at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California.