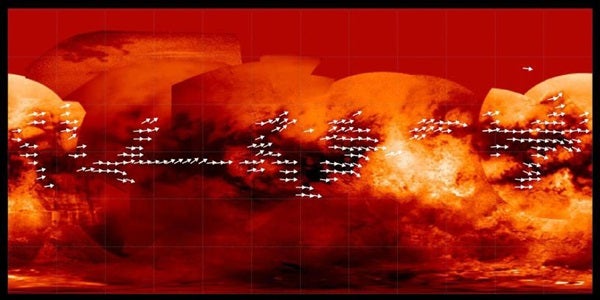

The arrows indicate the direction in which sand is inferred to be transported along dunes observed in Titan radar data. Underlying the arrows is a base map from Cassini’s imaging science subsystem. Many of the equatorial dark areas without arrows might have dunes but have not yet been imaged with radar. The dune orientations represent only the net effect of winds. It could be that sand transport only occurs on rare occasions, and winds from different directions can combine to yield the observed dune orientations.

Scientists who compiled 4 years of radar data collected by the Cassini spacecraft have mapped Titan’s vast dune fields, which may act like weather vanes to determine general wind direction on Saturn’s biggest moon.

Titan’s rippled dunes are generally oriented east-west. Surprisingly, their orientation and characteristics indicate that near the surface, Titan’s winds blow toward the east instead of toward the west. This means that Titan’s surface winds blow opposite the direction suggested by previous global circulation models.

“At Titan there are very few clouds, so determining which way the wind blows is not an easy thing, but by tracking the direction in which Titan’s sand dunes form, we get some insight into the global wind pattern,” says Ralph Lorenz, Cassini radar scientist at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. “Think of the dunes sort of like a weather vane, pointing us to the direction the winds are blowing.”

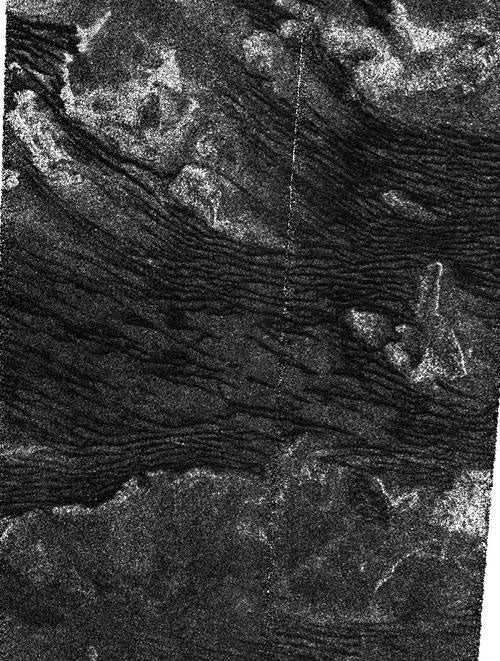

The area shown covers the southern boundary of an equatorial band where longitudinal dunes (dunes that form along the wind direction) are pervasive. Here the dunes are apparently created by winds locally coming from the west and north-west, and generally blowing toward the east. The dunes are interspersed with radar-bright features that are inferred to rise above the surrounding terrain.

In the lower part of the image there are no dunes at all, and the texture is more typical of featureless plains observed in many other areas of Titan that lack dunes. In this transition zone, the sand-sized particles that make up the dunes might not be so plentiful. In this case, insufficient sand to replenish the dunes makes them gradually disappear.

The wind pattern is important for planning future Titan explorations that might involve balloon-born experiments.

The group mapped some 16,000 dune segments from about 20 radar images, which they then digitized and combined to produce the new map.

Scientists believe Titan’s dunes are made up of hydrocarbon sand grains likely derived from organic chemicals in Titan’s smoggy skies. The dunes wrap around high terrain, which provides some idea of their height. They accumulate near the equator and may pile up there because drier conditions allow for easy transport of the particles by the wind. Titan’s higher latitudes contain lakes and may be “wetter” with more liquid hydrocarbons, not ideal conditions for creating dunes.