These raw, unprocessed images of Saturn’s moons Enceladus and Tethys were taken April 14, 2012, by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft.

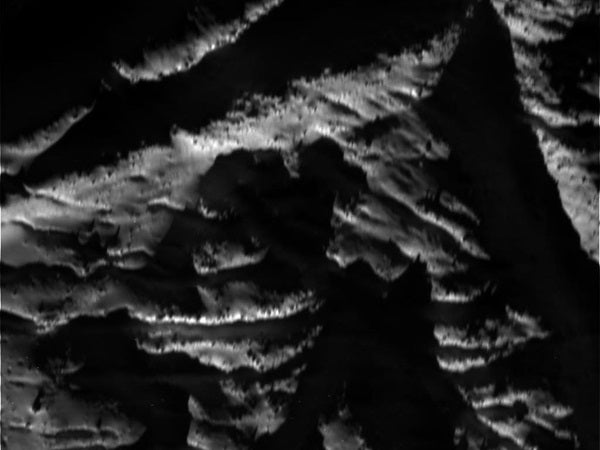

Cassini flew by Enceladus at an altitude of about 46 miles (74 kilometers). This flyby was designed primarily for the ion and neutral mass spectrometer to analyze, or “taste,” the composition of the moon’s south polar plume as the spacecraft flew through it. Cassini’s path took it along the length of Baghdad Sulcus, one of Enceladus’ “tiger stripe” fractures from which jets of water ice, water vapor , and organic compounds spray into space. At this time, Baghdad Sulcus is in darkness, but that was not an obstacle for another instrument, the composite infrared spectrometer, which can see features by their surface temperatures and which also took measurements during this flyby.

As soon as daylight passed into the spacecraft’s remote sensing instruments’ line of sight, Cassini’s cameras acquired images of the surface. The wide-angle-camera image included in the new batch, taken from around the time of closest approach, has some smearing from the movement of the spacecraft during the exposure, but still shows the surface in vivid detail.

Cassini’s cameras also imaged Enceladus’ south polar plume at a high phase angle as the satellite appeared as a thin crescent and the plume was backlit.

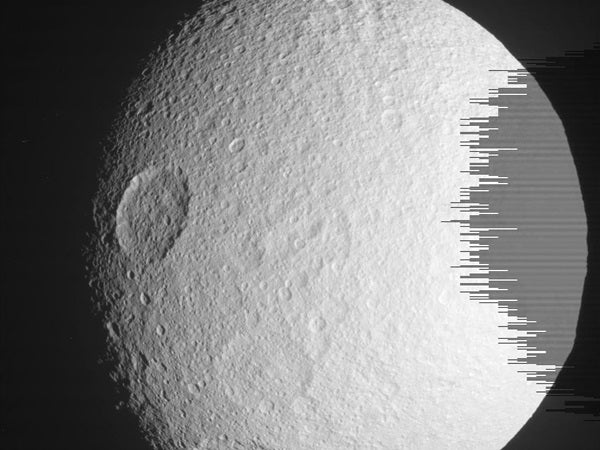

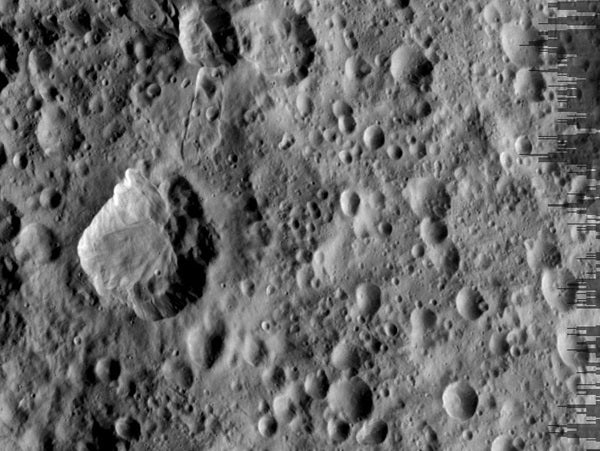

After the Enceladus encounter, Cassini passed the moon Tethys with a closest approach distance of about 5,700 miles (9,100 kilometers). This was Cassini’s best imaging encounter with Tethys since a targeted encounter in September 2005. The 2005 encounter, with a closest approach distance of about 930 miles (1,500 kilometers), provided the images of Tethys with the best resolution and captured views of the side of Tethys that faces Saturn in its orbit. This new encounter examined the opposite side of Tethys, providing some of the highest-resolution images of the side that faces away from Saturn. Cassini acquired a 22-frame mosaic of this side, which features the large impact basin named Odysseus. Scientists will use these new data in conjunction with images from previous encounters to create digital elevation maps of the moon’s surface.