Taking a long-weekend road trip, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft successfully glided near nine saturnian moons, sending back a stream of raw images as mementos of its adrenaline-fueled expedition. The spacecraft sent back particularly intriguing images of the moons Dione and Rhea.

The Dione and Rhea pictures are the highest resolution views yet of parts of their surfaces. The views of the southern part of Dione’s leading hemisphere (the part of the moon that faces forward in its orbit around Saturn) and the equatorial region of Rhea’s leading hemisphere are more detailed than the last time we saw these terrains with NASA’s Voyager spacecraft in the early 1980s.

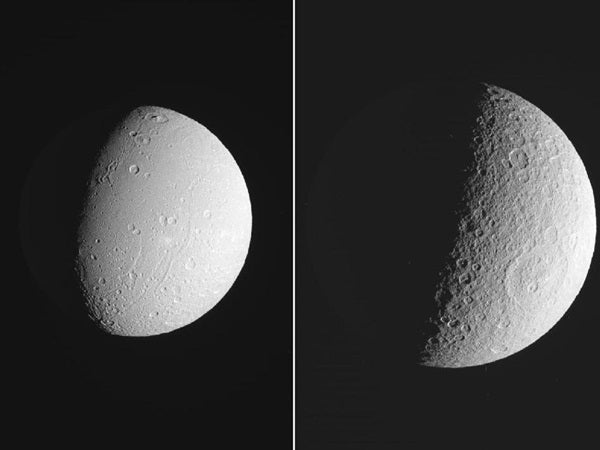

Of the five big icy moons of Saturn, Dione and Rhea are often considered a pair because they orbit close to each other, are darker than the others, and exhibit similar patterns of light reflecting off them. These new images, however, highlight the differences between these sister moons.

Both images show similar geographic regions on each satellite. However, scientists can identify differences in geological histories of the two bodies from differences in the numbers and sizes of visible craters on their surfaces. The number and size of craters on a body’s surface help indicate the age of that surface — the more craters there are and the larger they are, the older the surface is.

Rhea, for example, shows ancient, intense bombardments throughout this region. However, the same region of Dione is divided into distinct areas that exhibit variations in the number and size of preserved craters. In particular, while parts of Dione are heavily cratered like Rhea, there are other areas covered by relatively smooth plains. Those areas have many small craters, but few large impact scars, which indicate that they are geologically younger than the heavily cratered areas. The smooth plains must have been resurfaced at some point in Dione’s past — an event that seems to be missing from Rhea’s geological history on this side of the moon.

Images of the moon Mimas, captured just before it went into shadow behind Saturn, will be compared to thermal maps made earlier this year that showed an unexpected “Pac-Man” heat pattern.

Cassini also caught a picture of the tiny 3-mile-wide (4 kilometers) moon Pallene, in front of the planet Saturn, which is more than 75,000 miles (120,000 km) wide at its equator.

Cassini’s elliptical orbital pattern around Saturn means it can target moons for flybys about once or twice a month. The flybys on this particular Cassini road trip were “non-targeted” flybys, meaning navigators did not refine Cassini’s path to fly over particular points on each moon.

Cassini’s long weekend started October 14, at 5:07 p.m. UTC (9:07 a.m. PDT), when it passed by Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, at an altitude of 107,104 miles (172,368 km) above the surface. Then came a whirlwind 21 hours in which Cassini flew by Polydeuces at 72,406 miles (116,526 km), Mimas at 43,465 miles (69,950 km), Pallene at 22,443 miles (36,118 km), Elesto at 30,109 miles (48,455 km), Methone at 65,783 miles (105,868 km), Aegaeon at 60,120 miles (96,754 km) and Dione at 19,704 miles (31,710 km). Cassini’s last visit — Rhea at 24,079 miles (38,752 km) — took place at 6:47 a.m. UTC October 17 (10:47 p.m. PDT on October 16).

Scientists decided in advance which observations they wanted to make while the spacecraft was cruising past all the moons. They chose to obtain images of Titan, Mimas, Pallene, Dione, and Rhea. They also obtained thermal scans of Mimas, Dione, and Rhea.