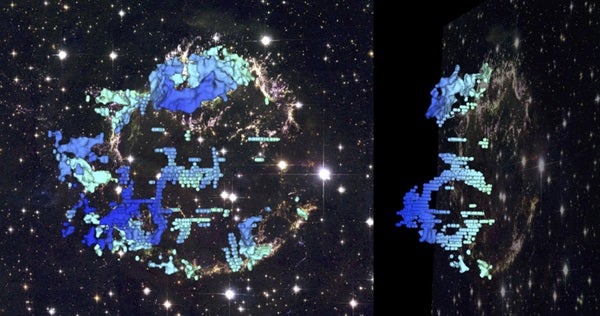

“Our three-dimensional map is a rare look at the insides of an exploded star,” Said Dan Milisavljevic of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA).

About 340 years ago, a massive star exploded in the constellation Cassiopeia. As the star blew itself apart, extremely hot and radioactive matter rapidly streamed outward from the star’s core, mixing and churning outer debris. The complex physics behind these explosions is difficult to model, even with state-of-the-art simulations run on some of the world’s most powerful supercomputers. However, by carefully studying relatively young supernova remnants like Cas A, astronomers can investigate various key processes that drive these titanic stellar explosions.

“We’re sort of like bomb squad investigators. We examine the debris to learn what blew up and how it blew up,” said Milisavljevic. “Our study represents a major step forward in our understanding of how stars actually explode.”

To make the 3-D map, Milisavljevic and co-author Rob Fesen of Dartmouth College examined Cas A in near-infrared wavelengths of light using the Mayall 4-meter telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory, southwest of Tucson, AZ. Spectroscopy allowed them to measure expansion velocities of extremely faint material in Cas A’s interior, which provided the crucial third dimension.

They found that the large interior cavities appear to be connected to — and nicely explain — the previously observed large rings of debris that make up the bright and easily seen outer shell of Cas A. The two most well-defined cavities are 3 and 6 light-years in diameter, and the entire arrangement has a Swiss cheese-like structure.

The bubble-like cavities were likely created by plumes of radioactive nickel generated during the stellar explosion. Since this nickel will decay to form iron, Milisavljevic and Fesen predict that Cas A’s interior bubbles should be enriched with as much as a tenth of a solar mass of iron. This enriched interior debris hasn’t been detected in previous observations, however, so next-generation telescopes may be needed to find the “missing” iron and confirm the origin of the bubbles.