Armchair astrophysicists rejoice: Now, you can help scientists find gravity waves — ripples in the fabric of space-time caused by spinning neutron stars. All you need is a computer, a fast connection to the Internet, and the Einstein@Home screensaver.

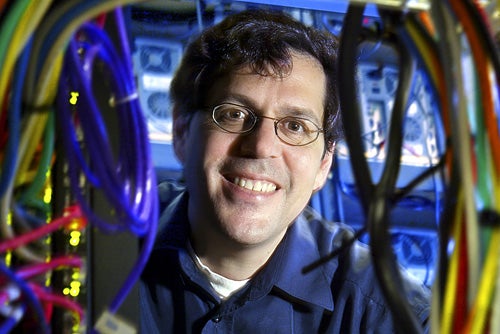

Bruce Allen, a professor of physics at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee (UWM), and leader of the Einstein@Home project, announced Saturday he was “throwing open the doors” to the public at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington, D.C. The project is the result of collaboration between UWM, the California Institute of Technology, and the Albert Einstein Institute in Germany.

The number of people running Einstein@Home has increased nearly 4 times since Saturday’s announcement. Allen told Astronomy he expects the project to gain its 30,000th user sometime today.

“Most of what exists in space is not visible,” says Allen. Finding gravitational waves “gives us another mechanism for learning about black holes and other space events firsthand.”

Einstein’s general theory of relativity predicts that objects such as spinning superdense neutron stars, collapsing and exploding stars, and black holes emit gravity waves, which move unseen through the universe, subtly distorting the world around us.

Although these waves have gone undetected so far, astronomers have seen their effects. For example, when a radio-emitting neutron star known as a pulsar is paired up with another star, the pulsar gradually tracks an ever-smaller orbit. The orbital energy it loses matches the energy relativity predicts the pulsar will emit as gravity waves.

Just as light carries information about a star’s surface to Earth, gravitational ripples in space-time will bring us invaluable clues about the interiors of stars and the nature of gravity itself. Three facilities — two in the United States and one in Germany — are actively searching for these waves and have collected massive amounts of data. Einstein@Home is designed to sift through hundreds of hours of these observations for signs of a passing gravity wave.

Searching for gravity waves

Three cutting-edge observatories have been built to find gravity waves. All work by ricocheting laser beams between mirrors as scientists look for minute distortions in the beams’ travel time. The Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory (LIGO) has one installation in Livingston, Louisiana, and a twin in Hanford, Washington. The German instrument, GEO 600, is near Hanover, Germany, and was built in collaboration with the United Kingdom.

These observatories face a difficult task. A typical gravity wave is expected to distort a laser’s path by less than a trillionth the width of a human hair. There’s no lack of signals in the data from these instruments, but separating spurious noise from the distortions produced by passing gravity waves requires loads of computer processing.

“Our current instruments will be able to see the merger of two neutron stars to tens of millions of light-years,” Allen told Astronomy. But because the system is less sensitive to impulsive events — like exploding stars — he noted, “We will probably only be able to see supernovae within our own galaxy, although this depends upon the detailed physics of what happens during a supernova, which is not fully understood.”

Scientists are conducting other searches for signals from these exotic sources, but Einstein@Home focuses on objects producing continuous waves, such as fast-spinning pulsars. This, says Allen, is the most computationally intensive task.

Einstein@Home looks for spinning neutron stars over the entire sky using the best 600 hours of data from LIGO observations made between October 2003 and January 2004. Scientists expect the next science run, to begin later this year, will be at least twice as sensitive.

Einstein@Home downloads data from the LIGO Scientific Collaboration through an Internet connection. Because these “work units” are rather large, Allen suggests only those people with a broadband Internet connection — cable modem or DSL — join the project. The program will process real LIGO data as a background task according to preferences you set. When Einstein@Home completes each work unit, it reports the results back and retrieves another block of data.

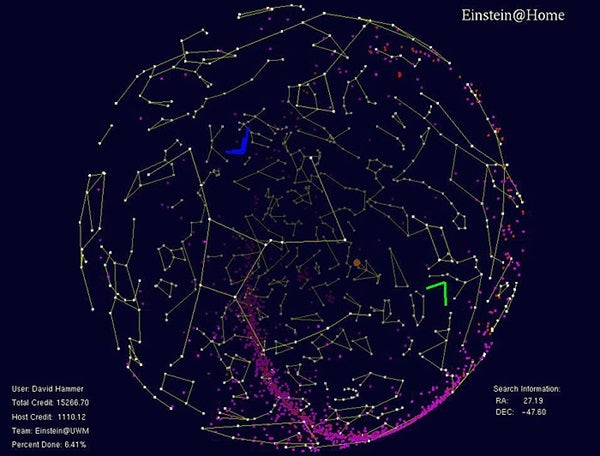

When the computer is performing no other tasks, Einstein@Home displays an attractive celestial sphere showing the brightest stars, constellation lines, a plot of known pulsars and supernova remnants, and symbols for the three gravity-wave detectors. A cursor slowly moves across the globe, charting the location of data currently being processed.

Einstein@Home scores computers by the amount of data they process, and users can join forces with others to collaborate as teams. The software is available for computers running the Microsft Windows, Macintosh OS X, and Linux operating systems. (The current Mac version does not display the screensaver, and installing the software requires use of Terminal’s command line. Allen says a new installer fixing these problems should be available in a few weeks.)

Einstein@Home is a project of World Year of Physics 2005, which celebrates the centennial of Albert Einstein’s “miraculous year.” In 1905, Einstein published three groundbreaking scientific advances including relativity and an explanation for the photoelectric effect.

Once you’ve set up an account and have the software running, you can join Astronomy‘s Einstein@Home team. Please note that it takes about a week to accumulate computation credits, and only members who have received a credit are listed as “active.”