Black holes are defined by just two simple characteristics — mass and spin. While astronomers have long been able to measure black hole masses very effectively, determining their spins has been much more difficult.

In the past decade, astronomers have devised ways of estimating spins for black holes at distances greater than several billion light-years away, meaning we see the region around black holes as they were billions of years ago. However, determining the spins of these remote black holes involves several steps that rely on one another.

“We want to be able to cut out the middle man, so to speak, of determining the spins of black holes across the universe,” said Rubens Reis of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

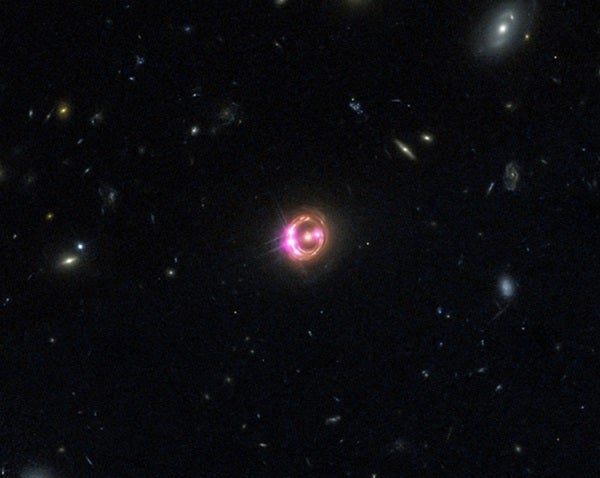

Reis and his colleagues determined the spin of the supermassive black hole that is pulling in surrounding gas, producing an extremely luminous quasar known as RX J1131-1231 (RX J1131). Because of fortuitous alignment, the distortion of space-time by the gravitational field of a giant elliptical galaxy along the line of sight to the quasar acts as a gravitational lens that magnifies the light from the quasar. Gravitational lensing, first predicted by Einstein, offers a rare opportunity to study the innermost region in distant quasars by acting as a natural telescope and magnifying the light from these sources.

“Because of this gravitational lens, we were able to get very detailed information on the X-ray spectrum — that is, the amount of X-rays seen at different energies — from RX J1131,” said Mark Reynolds also of the University of Michigan. “This in turn allowed us to get a very accurate value for how fast the black hole is spinning.”

The X-rays are produced when a swirling accretion disk of gas and dust that surrounds the black hole creates a multimillion-degree cloud, or corona, near the black hole. X-rays from this corona reflect off the inner edge of the accretion disk. The strong gravitational forces near the black hole alter the reflected X-ray spectrum. The larger the change in the spectrum, the closer the inner edge of the disk must be to the black hole.

“We estimate that the X-rays are coming from a region in the disk located only about three times the radius of the event horizon, the point of no return for infalling matter,” said Jon M. Miller of Michigan. “The black hole must be spinning extremely rapidly to allow a disk to survive at such a small radius.”

For example, a spinning black hole drags space around with it and allows matter to orbit closer to the black hole than is possible for a non-spinning black hole.

By measuring the spin of distant black holes, researchers discover important clues about how these objects grow over time. If black holes grow mainly from collisions and mergers between galaxies, they should accumulate material in a stable disk, and the steady supply of new material from the disk should lead to rapidly spinning black holes. In contrast, if black holes grow through many small accretion episodes, they will accumulate material from random directions. Like a merry-go-round that is pushed both backward and forward, this would make the black hole spin more slowly.

The discovery that the black hole in RX J1131 is spinning at over half the speed of light suggests this black hole, observed at a distance of 6 billion light-years, corresponding to an age about 7.7 billion years after the Big Bang, has grown via mergers rather than pulling material in from different directions.

The ability to measure black hole spin over a large range of cosmic time should make it possible to directly study whether the black hole evolves at about the same rate as its host galaxy. The measurement of the spin of the RX J1131-1231 black hole is a major step along that path and demonstrates a technique for assembling a sample of distant supermassive black holes with current X-ray observatories.

Prior to the announcement of this work, the most distant black holes with direct spin estimates were located 2.5 billion and 4.7 billion light-years away.