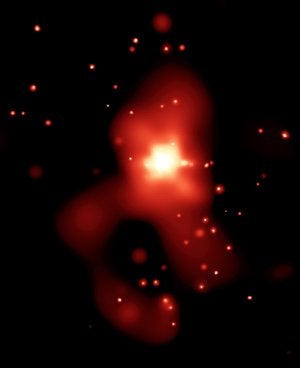

The image covers 237 x 290 arcseconds.

What do you get when two galaxies collide head-on? Astronomers believe the answer may lie just 100 million light-years away from Earth. Like the scene of a hit-and-run accident, a trail of cosmic debris has been left behind for investigators to sift through. Intense X-ray sources embedded in a 10th-magnitude elliptical galaxy called NGC 4261 point to a galaxy collision long ago.

With its high-resolution X-ray vision, NASA’s Chandra space observatory has imaged this stellar wreckage of black holes and neutron stars spread over 50,000 light-years. The Hubble Space Telescope previously imaged NGC 4261, located in the constellation Virgo, revealing a supermassive black hole swirling in the heart of the galaxy. What Chandra saw for the first time, however, is the optically invisible signature of a violent fusion between two galaxies billions of years ago that created the single elliptical galaxy we see today. Whereas optical remnants of galaxy collisions vanish relatively quickly, their X-ray fingerprints linger for hundreds of millions of years.

“From the optical and radio images, we knew something unusual was going on in the nucleus of this galaxy, but the real surprise turned out to be on the outer edges of the galaxy,” says Andreas Zezas of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) and lead author of this study. “Dozens of black holes and neutron stars were strung out across space like beads on a necklace.”

Publishing their findings in an upcoming issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters, the American team of astronomers believes Chandra’s detection of a string of X-ray sources reveals the destruction of a small, interloper galaxy. Gravitational tidal forces produced when this galaxy was ripped apart likely created shock waves that swept through NGC 4621. These shock waves created large tails that triggered the formation of massive stars. Many of these heavyweights evolved into neutron stars and black holes, and those with stellar companions began to shine in X-rays as gas was sucked into their huge gravity wells.

Just how elliptical galaxies form has been the subject of much debate over the years. Theoretical models, computer simulations, and optical images of galactic tails, shells, ripples, arcs, and other structures all point to galaxy collisions and mergers.

“This discovery shows that X-ray observations may be the best way to identify the ancient remains of mergers between galaxies,” explains co-investigator Lars Hernquist of CfA. Having observed with Chandra for 35 hours, Zezas and his colleagues argue their data is the best evidence yet for elliptical galaxy births.