The journey — which involved spending nights gazing at the southern sky, tours of historic Incan sites like Machu Picchu, and a trip to Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory — culminated with my second-ever glimpse of the Moon blotting out the Sun. And though the main event was unbeatable, the road there was nearly as brilliant.

Down through Peru

Following some initial travel troubles after my departure the morning of June 23, including a missed connecting flight and a checked bag orphaned in Miami, I ultimately made it to Lima, Peru, by the wee hours of June 25.

With no fresh clothing and just a couple of hours before our next departure, I immediately attempted to wash my essentials in the sink. Surely, the hair dryer will help me dry my damp clothing, I thought. And it did. But what I didn’t count on was the resulting steam bath that left me sweating ferociously as I introduced myself to my new TravelQuest International colleagues and clients.

After my soggy introductions, we set off for our flight from Lima to Cusco, Peru. Upon our arrival, we quickly hopped onto buses and headed north. On the way, we took a detour to visit a small, rustic village named Chinchero. Here, locals have perfected the art of weaving Peruvian clothing, which is often made using alpaca, llama, or sheep’s wool stained with naturally colorful dyes.

Next, we ventured onward to our hotel in Peru’s Yucay District, a fertile farming region tucked away in the Andean highlands in an area also known as the Sacred Valley of the Incas. Not only was the hotel there beautiful and packed with interesting native vegetation — such as the tamarillo, an egg-shaped tree tomato — but the hotel staff was also incredibly accommodating. At night, they even shut off many of the hotel’s lights so we could carry out some southern stargazing under Sacred Valley’s extremely dark skies.

Exploring the southern sky

Because this was my first time in the Southern Hemisphere, I initially struggled to orient myself under the new celestial tapestry — and the sheer number of stars visible without significant light pollution didn’t help me get my bearings. Fortunately, the stars Alpha and Beta Centauri are fantastically easy to spot. Aptly nicknamed “The Southern Pointers,” these bright stars served as a guide to the go-to target for most first-time southern observers: the constellation Crux the Southern Cross.

After briefly dissecting the Southern Cross, we targeted the nearby globular cluster Omega Centauri (NGC 5139) through one of the many telescopes brought by the tour participants. From there, we hopped around the sky tracking down some of the brightest stars, such as Spica in Virgo. A short time later, we were treated to views of Vega and Altair as they rose above the mountains to the northeast, providing us with a glimpse of two of the three bright stars that make up the easy-to-spot asterism known (at least to us northerners) as the Summer Triangle. We also spent a good deal of time poking around the constellation Scorpius, stopping to admire the Scorpion’s glowing heart, the ruby-red star Antares.

Then there was the Milky Way itself. Flanked above by a brilliant Jupiter and below by an easily visible Saturn, the cosmic river flowed across the dark sky with striking clarity. We paid particular attention to the Milky Way’s shadowy voids, caused by light-blocking gas and dust between us and the billions of stars in our galaxy’s disk. For the ancient Incas, these dark clouds, rather than outlines traced by bright stars, formed their constellations.

Specifically, we had a great view of the Incan constellation Yacana the Llama, whose two glowing eyes are marked by Alpha and Beta Centauri. This massive dark constellation spans some 40° from tip to tail and was thought to be a shadow cast by a great llama drinking from the cosmic river that is the Milky Way. Upside down and below the Llama is its nursing cria, the Baby Llama.

Perched between the Llama and the Southern Cross is Yutu the Tinamou (a ground bird similar to the partridge), which is also known as the Coalsack. To the lower right of Yutu sits Hanp’atu the Toad, so named because its arrival in the morning sky near the end of October corresponds with an increase in the croaking of toads, which the Incas thought signaled coming rain.

Beneath this incredibly dark southern sky, accompanied by the sounds of countless stray dogs arguing in the distance, I felt a sense of serenity wash over me as I gazed upward. In fact, after our impromptu star party, I recall reclining back on a bench to take everything in when a friendly hotel employee wandered up and asked, “¿Tranquila, sí?” And it truly was. There are only a handful of times in my entire life that I remember being in such a relaxed and peaceful place.

Ancient Incan ruins

The next day, June 26, we packed our bags and boarded a train to the town of Aguas Calientes, unofficially known as Machu Picchu Pueblo. This small but bustling village is located in a valley below the famous Incan ruins of Machu Picchu, which were built around the 15th century.

Also within these ruins was a particularly notable structure: the famed Temple of the Sun. While most of Machu Picchu’s buildings have rectangular foundations, the Temple of the Sun has a semicircular design that includes two small trapezoidal windows. These are precisely oriented so that sunlight passes perfectly through one window during winter solstice and the other during summer solstice.

Surprisingly, the town below Machu Picchu was almost as fascinating as the ancient ruins. Although its primary purpose clearly was to tend to Machu Picchu’s roughly 1.3 million annual tourists, this did not diminish the town’s appeal. In addition to countless shops, there were many restaurants with delicious food, as well as a town square centered around a statue of Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui. This ninth ruler of the Kingdom of Cusco, whose name roughly translates to “Earth-shaker,” is often credited with establishing the Incan Empire through conquests of the Cusco Valley and beyond, eventually expanding the Incan reach in western South America. According to many archeologists, Machu Picchu itself was built as a summer home for Pachacuti.

After spending the night in Aguas Calientes, we returned to our previous hotel in Sacred Valley on June 27, where we took advantage of another beautiful night to again dissect the southern sky. The next day, we made a quick stop at the ancient hilltop fortress Sacsayhuaman, which means “the place where the hawk is situated,” before venturing to the bustling city of Cusco below, located just over a mile (2 kilometers) to the south.

Situated at an elevation of about 11,200 feet (3,400 meters), Cusco is more than 3,000 feet (915 m) higher than the ruins of Machu Picchu. Though this may not seem like much, I and many others noticed the difference. Because many of our group had already passed around a communal cold, the altitude was the final straw that put some of us on our backs. But while I was acclimating, many embarked on a walking tour of the historic city, which has steep and narrow cobblestone roads that vein through beautiful colonial-era buildings often built atop ancient Incan foundations. By nightfall, I willed myself to explore the city and ventured to the nearby town square, Plaza de Armas, where a makeshift car show exemplified the Peruvian spirit and energy that permeates the entire city.

Onward to Chile

Of course, as soon as I started getting used to Cusco’s altitude, it was time to press on to Chile. Specifically, we flew to the twin cities of La Serena and Coquimbo, located on the coast of the South Pacific. These two cities, each with a population over 200,000 and separated by only about 8 miles (13 km), would serve as our home base for the eclipse.

The day after our arrival, June 30, we were largely left to our own devices. This allowed me to explore the local markets, as well as casually stroll along the nearby beaches, where I unexpectedly found myself within just a few feet of a pair of resting sea lions.

By July 1, our anticipation of the eclipse had reached a fever pitch. In the morning, we distracted ourselves by going on a walking tour through La Serena. And that night, the nearly 300 people in our group met for a fantastic dinner supplemented by pre-eclipse talks by Paul Deans, a freelance astronomy writer and editor with more than four decades of experience; Jay Anderson, a meteorologist who specializes in predicting weather for eclipses; and me.

Eclipse day

Then came July 2, 2019: The day of the Great South American Eclipse.

Here, the local climate tends to produce fewer late-afternoon clouds, which is why we had secured a soccer field that would provide a primo view of the eclipse. Although we had exclusive access to the site, TravelQuest made sure to invite local schoolchildren, as well as some local vendors, to join us for what is usually a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

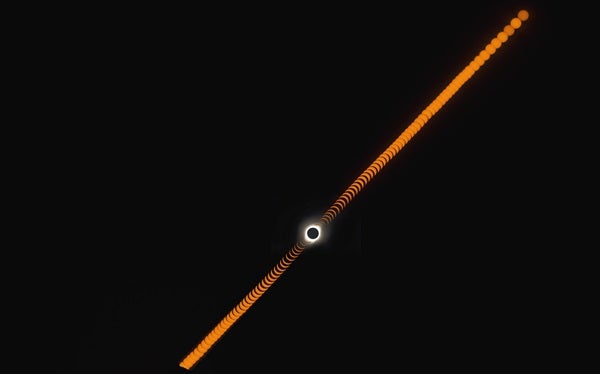

To ensure we would beat eclipse-related traffic, we left La Serena for the soccer field first thing in the morning, even though the main event wouldn’t occur until about 4:38 P.M. local time. Fortunately, the traffic was relatively mild, which meant we arrived with about seven hours to spare before first contact — when the Moon first starts its slow trek across the Sun. This gave the many dozens of eclipse chasers and photographers ample time to set up their equipment. And boy, did they bring equipment.

The closer we got to totality, the quieter everyone seemed to get. Then, just a few minutes before the Moon completely obscured the Sun’s disk, the chatter picked back up with a vengeance.

“Wow! Look at those shadow bands!” many exclaimed.

As the Sun’s disk was reduced to an incredibly thin crescent, the sunlight became increasingly collimated, much like laser light. This produced a well-known phenomenon called shadow bands, which are dancing streaks of light and dark that result from parallel beams of sunlight refracting through Earth’s turbulent atmosphere. It’s akin to why stars appear to shimmer. And for this eclipse, the shadow bands were out in full force.

Then, bam, the first diamond ring burst forth. Over the next few minutes, we were treated to a sight that most humans never get the opportunity to witness — one that is both terrifyingly bizarre and magnificently awestriking. As the first glaringly bright diamond ring faded away, the Sun’s corona came into full view. This few-million-degree aura of plasma is usually invisible to the naked eye, as the Sun’s blinding disk overpowers its faint glow. But during a total solar eclipse, the Sun’s disk is entirely blotted out, allowing the ethereal corona to steal the show.

Then, less than two and a half minutes after totality began, the second diamond ring all too soon marked the end of the main event. At this point, many veteran eclipse chasers, still in a state of pure bliss, lamented the validity of what’s become known as Sperling’s Eight Second Law. First published in the August 1980 issue of Astronomy magazine, this informal credo from author and telescope designer Norman Sperling basically states that every total solar eclipse lasts eight seconds. And I can absolutely confirm that’s how it feels.

As we watched the crescent Sun again begin to grow, we celebrated our good fortune with a champagne toast and delicious empanadas. Due to the soccer field being tucked between mountain ridges, we knew the Sun would set before we witnessed fourth contact, when the Sun and Moon finally part ways. But what we didn’t consider was that the Moon would still be taking a bite out of the top of the Sun at the same time the intervening mountain ridge started gobbling it up from the bottom. This temporarily left the visible portion of the Sun’s disk vaguely shaped like a simplified Bat-Signal, adding yet another memorable sight to a trip that a dozen scrapbooks couldn’t adequately capture.

A trip to Cerro Tololo

Although witnessing a total solar eclipse would have served as a fitting end to one of the most fantastic trips I’ve ever been on, we weren’t done just yet.

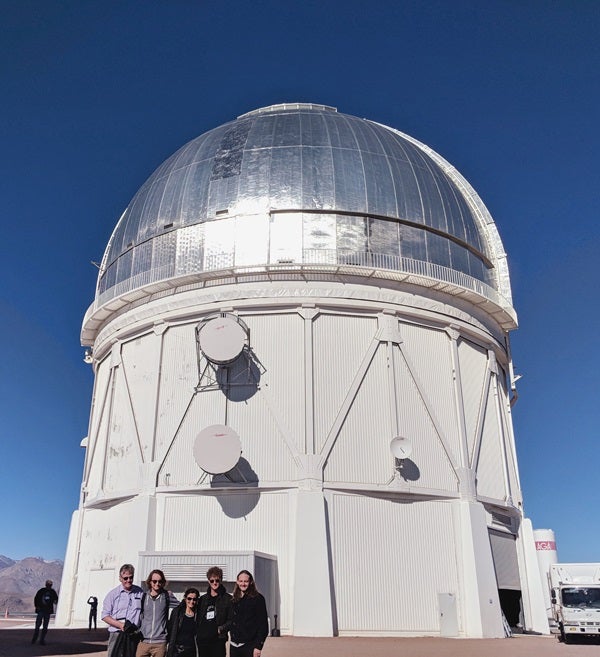

On July 4, while those in the U.S. were celebrating Independence Day with cookouts and fireworks, we set off for an arid, mountainous region in central Chile about 30 miles (50 km) southeast of La Serena. This location, thanks to its dark skies and calm atmosphere, is home to the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO).

Upon our arrival at CTIO, located some 7,200 feet (2,200 m) above sea level, we took in the expansive views from the mountaintop before beginning our tour. Over the course of the next few hours, we were treated to a behind-the-scenes look at CTIO’s two biggest telescopes: the 1.5-meter SMARTS telescope, part of the Small and Moderate Aperture Research Telescope System, and the famous 4-meter Victor M. Blanco Telescope.

The Blanco Telescope, which saw first light in 1976, was an observational beast in its heyday. And though newer telescopes have since greatly surpassed Blanco in size, thanks to the relatively recent installation of its sophisticated Dark Energy Camera (DECam), Blanco is once again making valuable contributions to astronomy.

The end of our tour of Cerro Tololo also signaled the end of our adventure through Peru and Chile. Although the entire journey took less than two weeks, the historical and astronomical sites — and sights — we experienced throughout will remain burned in my mind for the rest of my life.