Turbulence makes the universe magnetic, helps stars form, and spreads the heat from supernova explosions through the galaxy. “We now plan to study turbulence throughout the Milky Way,” Gaensler said. “Ultimately this will help us understand why some parts of the galaxy are hotter than others, and why stars form at particular times in particular places.”

Gaensler and his team studied a region of our galaxy about 10,000 light-years away in the southern constellation Norma. They used CSIRO’s Australia Telescope Compact Array because “it is one of the world’s best telescopes for this kind of work,” said Robert Braun from CSIRO Astronomy and Space Science.

The radio telescope was tuned to receive radio waves that come from the Milky Way. As these waves travel through the swirling interstellar gas, one of their properties — polarization — is slightly altered, and the radio telescope can detect this. Polarization is the direction the waves “vibrate.” Light can be polarized: Some sunglasses filter out light polarized in one direction while letting through other light.

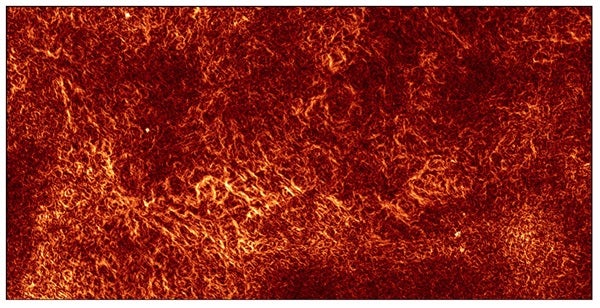

The researchers measured the polarization changes over an area of sky and used them to make a spectacular image of overlapping entangled tendrils, resembling writhing snakes. The “snakes” are regions of gas where the density and magnetic field are changing rapidly as a result of turbulence.

The “snakes” also show how fast the gas is churning — an important number for describing the turbulence. Team member Blakesley Burkhart from the University of Wisconsin-Madison made several computer simulations of turbulent gas moving at different speeds. These simulations resembled the snakes’ picture, with some matching the real picture better than others. By picking the best match, the team concluded that the speed of the swirling in the turbulent interstellar gas is around 43,500 mph (70,000 km/h) — relatively slow by cosmic standards.

Turbulence makes the universe magnetic, helps stars form, and spreads the heat from supernova explosions through the galaxy. “We now plan to study turbulence throughout the Milky Way,” Gaensler said. “Ultimately this will help us understand why some parts of the galaxy are hotter than others, and why stars form at particular times in particular places.”

Gaensler and his team studied a region of our galaxy about 10,000 light-years away in the southern constellation Norma. They used CSIRO’s Australia Telescope Compact Array because “it is one of the world’s best telescopes for this kind of work,” said Robert Braun from CSIRO Astronomy and Space Science.

The radio telescope was tuned to receive radio waves that come from the Milky Way. As these waves travel through the swirling interstellar gas, one of their properties — polarization — is slightly altered, and the radio telescope can detect this. Polarization is the direction the waves “vibrate.” Light can be polarized: Some sunglasses filter out light polarized in one direction while letting through other light.

The researchers measured the polarization changes over an area of sky and used them to make a spectacular image of overlapping entangled tendrils, resembling writhing snakes. The “snakes” are regions of gas where the density and magnetic field are changing rapidly as a result of turbulence.

The “snakes” also show how fast the gas is churning — an important number for describing the turbulence. Team member Blakesley Burkhart from the University of Wisconsin-Madison made several computer simulations of turbulent gas moving at different speeds. These simulations resembled the snakes’ picture, with some matching the real picture better than others. By picking the best match, the team concluded that the speed of the swirling in the turbulent interstellar gas is around 43,500 mph (70,000 km/h) — relatively slow by cosmic standards.