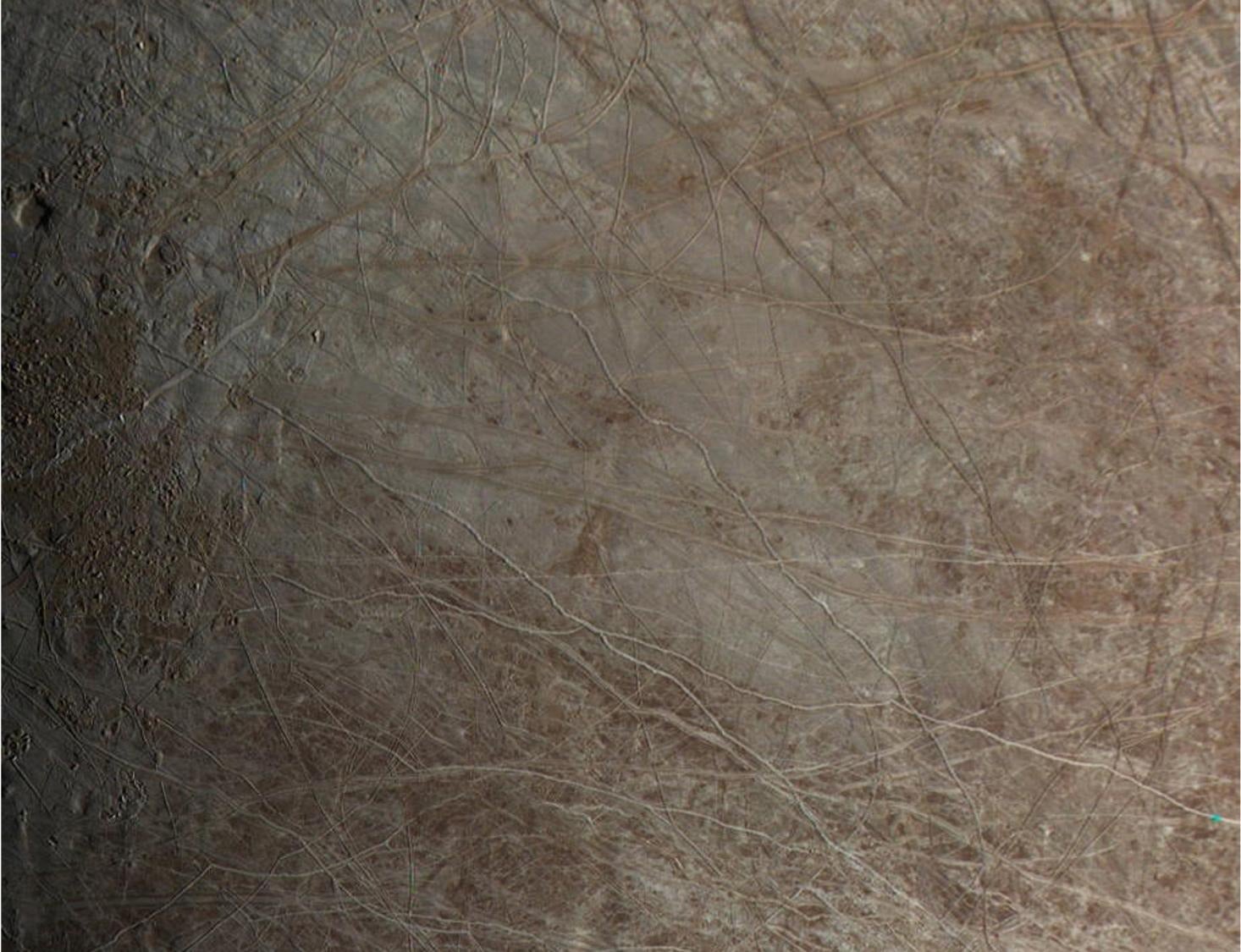

A series of ring structures on the surface of Europa may give hints to the thick ice shell below — and could affect the potential for life on one of the most promising places to find it in our solar system. In a paper recently published in Science Advances, a team of planetary scientists analyzed the Callanish and Tyre multiring basins (meteor crater impacts that formed concentric ring structures on the surface of Europa).

The team essentially found that an ice shell greater than 12 miles (20 kilometers) could account for these structures. If the icy layer was any thinner, then the ring patterns wouldn’t have formed, study author Shigeru Wakita of MIT says. The data shows a hard ice shell on the surface of Europa (lithosphere), about 3.7 to 5 miles (6 to 8 km) deep. Below that is at least 7.4 miles (12 km) of warmer ice (asthenosphere) that convects up toward the ice shell.

The team’s work provides insight into Europa’s interior structure, including what kind of chemical constraints it could place on the ocean below. “Our finding of the ice shell thickness is consistent with the previous work based on the observation, but we further constrain the ice structure, comprising the lithosphere and asthenosphere,” Wakita says. “Therefore, we need to care that Europa’s ocean lays beneath the asthenosphere, not the lithosphere.”

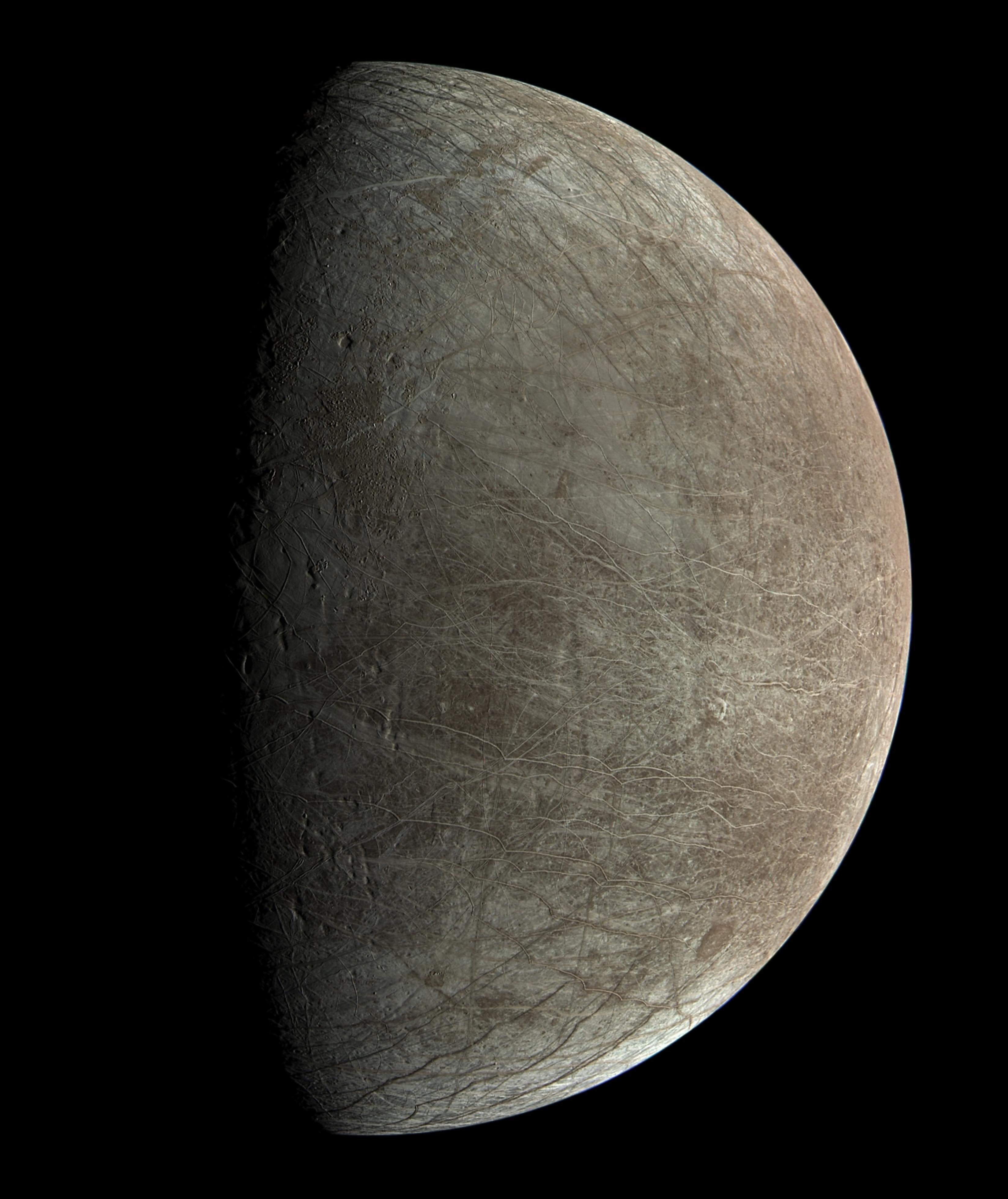

Water on Europa

Scientists think the best place to find life beyond Earth is in the presence of water, which is necessary for all life on Earth. And Europa has plenty of it!

Wakita also mentioned that the thick ice shell could provide better protection for life on Europa. Jupiter regularly bathes the satellite in radiation that would kill most life on Earth, thus, a thicker ice shell provides better insulation. The disadvantage of having this icy protection is that you don’t have a lot of transport between the surface and the ocean. This inhibits the ability of some surface compounds that could be used as nutrients, from reaching the ocean. It is believed that a violent meteor impact would be needed to allow this transportation to give way — one that breaks the ice shell.

Recent evidence has shown that Europa may have geysers, like those seen on Saturn’s moon Enceladus. Wakita says that, while it’s not his area of expertise, if the geysers come from the ocean through cracks in the ice, the hard ice shell may complicate the passage. “On the other hand, the asthenosphere may facilitate the geyser to reach the surface,” he says.

In the next decade or so, two spacecraft will make their way to Jupiter’s moons: the European Space Agency’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, which launched in April 2023, and NASA’s Europa Clipper, set for launch in fall 2024. Both missions could tell us more about the interior of Europa, and confirm or refine the model set forth in this paper.