A day on Neptune lasts precisely 15 hours, 57 minutes, and 59 seconds, according to the first accurate measurement of its rotational period made by Erich Karkoschka from University of Arizona, Tucson.

His result is one of the largest improvements in determining the rotational period of a gas planet in almost 350 years since Italian astronomer Giovanni Cassini made the first observations of Jupiter’s Red Spot.

“The rotational period of a planet is one of its fundamental properties,” said Karkoschka. “Neptune has two features observable with the Hubble Space Telescope that seem to track the interior rotation of the planet. Nothing similar has been seen before on any of the four giant planets.”

Unlike the rocky planets — Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars — which behave like solid balls spinning in a rather straightforward manner, the giant gas planets — Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune — rotate more like giant blobs of liquid. Because they are believed to consist of mainly ice and gas around a relatively small solid core, their rotation involves a lot of sloshing, swirling, and roiling, which has made it difficult for astronomers to get an accurate grip on exactly how fast they spin around.

“If you looked at Earth from space, you’d see mountains and other features on the ground rotating with great regularity, but if you looked at the clouds, they wouldn’t because the winds change all the time,” Karkoschka said. “If you look at the giant planets, you don’t see a surface, just a thick cloudy atmosphere.”

“On Neptune, all you see is moving clouds and features in the planet’s atmosphere. Some move faster, some move slower, some accelerate, but you really don’t know what the rotational period is, if there even is some solid inner core that is rotating.”

In the 1950s, when astronomers built the first radio telescopes, they discovered that Jupiter sends out pulsating radio beams, like a lighthouse in space. Those signals originate from a magnetic field generated by the rotation of the planet’s inner core.

No clues about the rotation of the other gas giants, however, were available because any radio signals they may emit are being swept out into space by the solar wind and never reach Earth.

“The only way to measure radio waves is to send spacecraft to those planets,” Karkoschka said. “When Voyager 1 and 2 flew past Saturn, they found radio signals and clocked them at exactly 10.66 hours, and they found radio signals for Uranus and Neptune, as well. So based on those radio signals, we thought we knew the rotation periods of those planets.”

But when the Cassini probe arrived at Saturn 15 years later, its sensors detected its radio period had changed by about 1 percent.

Karkoschka said that because of its large mass, it was impossible for Saturn to incur that much change in its rotation over such a short time.

“Because the gas planets are so big, they have enough angular momentum to keep them spinning at pretty much the same rate for billions of years,” he said. “So something strange was going on.”

Even more puzzling was Cassini’s later discovery that Saturn’s northern and southern hemispheres appear to be rotating at different speeds.

“That’s when we realized the magnetic field is not like clockwork but slipping,” Karkoschka said. “The interior is rotating and drags the magnetic field along, but because of the solar wind or other, unknown influences, the magnetic field cannot keep up with respect to the planet’s core and lags behind.”

Other scientists before him had observed Neptune and analyzed images, but nobody had sleuthed through 500 of them.

“When I looked at the images, I found Neptune’s rotation to be faster than what Voyager observed,” Karkoschka said. “I think the accuracy of my data is about 1,000 times better than what we had based on the Voyager measurements — a huge improvement in determining the exact rotational period of Neptune, which hasn’t happened for any of the giant planets for the last 3 centuries.”

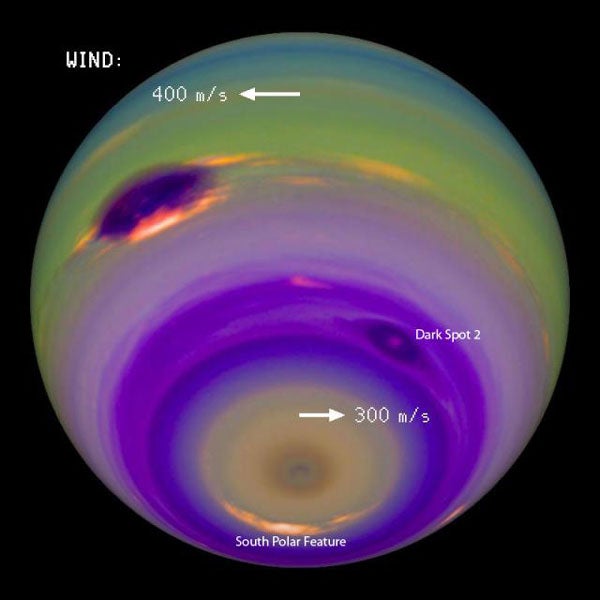

Two features in Neptune’s atmosphere, Karkoschka discovered, stand out in that they rotate about 5 times more steadily than even Saturn’s hexagon, the most regularly rotating feature known on any of the gas giants.

Named the South Polar Feature and the South Polar Wave, the features are likely vortices swirling in the atmosphere, similar to Jupiter’s famous Red Spot, which can last for a long time due to negligible friction. Karkoschka was able to track them over the course of more than 20 years.

An observer watching the massive planet turn from a fixed spot in space would see both features appear exactly every 15.9663 hours, with less than a few seconds of variation.

“The regularity suggests those features are connected to Neptune’s interior in some way,” Karkoschka said. “How they are connected is up to speculation.”

One possible scenario involves convection driven by warmer and cooler areas within the planet’s thick atmosphere, analogous to hot spots within the Earth’s mantle, giant circular flows of molten material that stay in the same location over millions of years.

“I thought the extraordinary regularity of Neptune’s rotation indicated by the two features was something really special,”

Karkoschka said.

“So I dug up the images of Neptune that Voyager took in 1989, which have better resolution than the Hubble images, to see whether I could find anything else in the vicinity of those two features. I discovered six more features that rotate with the same speed, but they were too faint to be visible with the Hubble Space Telescope, and visible to Voyager only for a few months, so we wouldn’t know if the rotational period was accurate to the six digits. But they were really connected. So now we have eight features that are locked together on one planet, and that is really exciting.”

In addition to getting a better grip on Neptune’s rotational period, the study could lead to a better understanding of the giant gas planets in general.

“We know Neptune’s total mass but we don’t know how it is distributed,” Karkoschka said. “If the planet rotates faster than we thought, it means the mass has to be closer to the center than we thought. These results might change the models of the planets’ interior and could have many other implications.”