On the afternoon of July 6, 1924, John Moore’s funeral was interrupted. A meteorite, trailing smoky plume, announced its arrival with a series of thunderous bangs.

As the attendees walked over to the site of the crash, they discovered a meteorite buried four feet (1.2 meters) deep into the soil. “Being a burial, they happened to have shovels and immediately dug out the meteorite and put it on display in the town,” says Richard Binzel, an astrophysicist at MIT who organized the meteorite’s centennial homecoming.

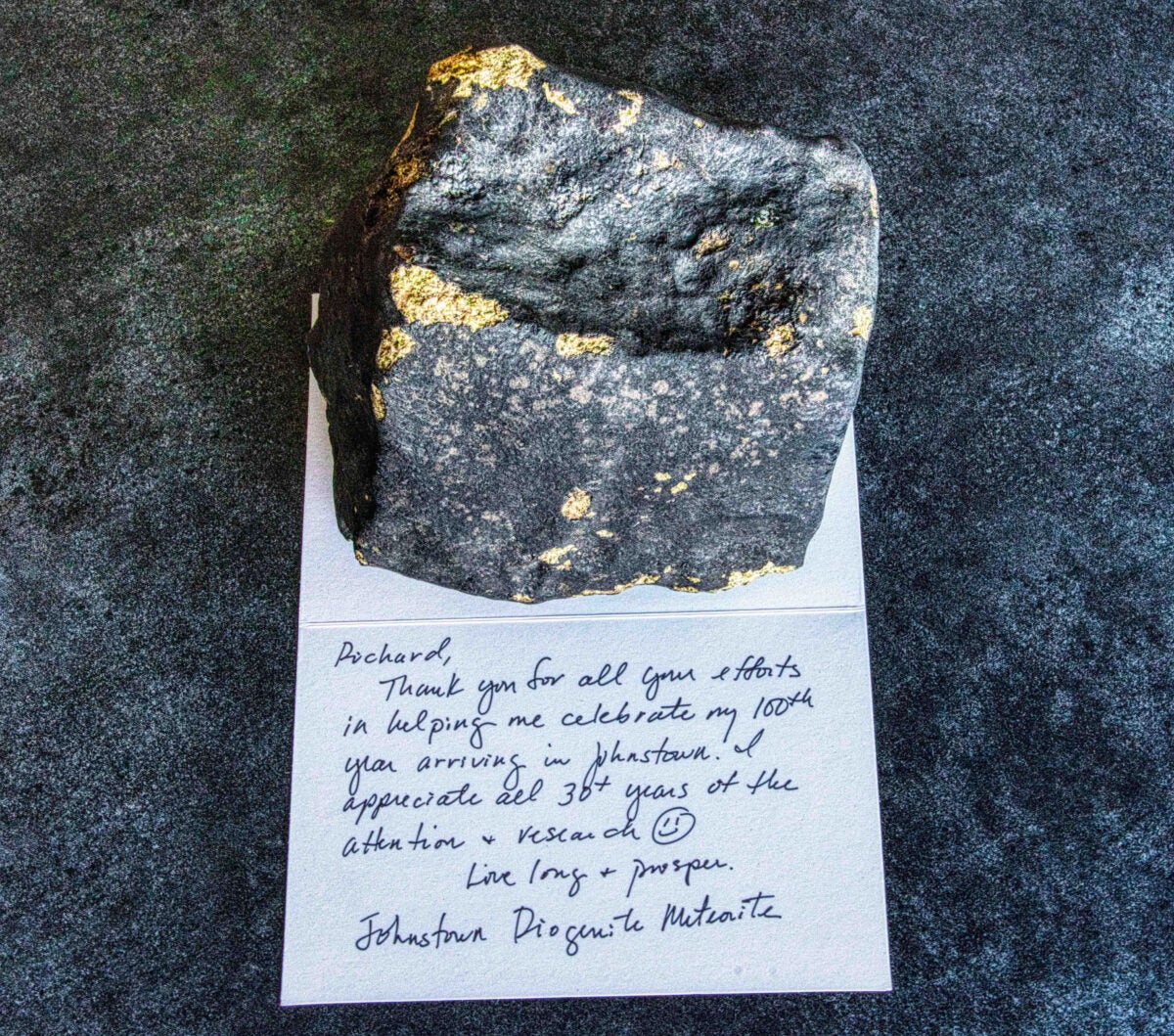

One hundred years later, the Johnstown meteorite returned to its impact site, where citizens commemorated the centennial anniversary of its fall to Earth with presentations, a rock and gem show, and a historical marker at the landing site.

Not many meteorites are seen crashing into Earth. Most never make it past our planet’s atmosphere, while many that do splash into the oceans instead. The Johnstown meteorite is particularly unique because several people witnessed its fall, and those who saw it recovered pieces of it.

And, decades later, the Johnstown meteorite became a link to understanding a whole class of meteorites called diogenites, catapulting the specimen to additional fame in the astronomical community.

A chip off the old block

The rock that crashed the funeral came from the asteroid 4 Vesta, the second most massive body in the main belt between Mars and Jupiter. But it was only in the 1990s that researchers could trace the Johnstown meteorite to its parent body. “Meteorites are free samples from space, but they don’t come with the return address label,” says Binzel.

The Johnstown meteorite is classified as a diogenite and contains sparkling green crystals that reveal how it formed. These crystals occur when magma cools slowly beneath the parent body’s surface. Together with two other types of meteorites, known as howardites and eucrites, diogenites form a larger group of meteorites known as HED meteorites, which researchers surmise must all come from Vesta.

“These fragments we thought were coming from Vesta must have been very deeply excavated,” says Binzel. Astronomers believed these pieces were thrown out of Vesta following an impact.

But how did a piece of Vesta, which resides in the main belt, get to Earth?

A path to Earth

With the advent of CCDs, astronomers discovered that Vesta does not orbit alone. Deep images showed many smaller asteroids orbiting parallel to Vesta. The orbits of these bodies fall in unstable regions caused by Jupiter’s gravity, which can knock one of these fragments into a path toward Earth’s orbit. Binzel explains that these areas are like escape hatches or delivery zones where fragments escape the main belt into Earth’s orbit.

“The key was that we were finding these little fragments of Vesta like Hansel and Gretel’s breadcrumbs going from Vesta to these escape hatches, and we’ve discovered a pathway for delivering meteorite samples from Earth,” Binzel says.

In 1996, Binzel and his team imaged Vesta with the Hubble Space Telescope and discovered a 285-mile-wide (460 kilometers), 8-mile-deep (13 km) impact basin on Vesta.

“The smoking gun of that impact basin was a chance to look deep inside Vesta,” says Binzel. His team estimated some 1 percent of Vesta had been blown off by the impact that created it — “a volume sufficient to account for the family of small Vesta-like asteroids that extends to dynamical source regions for meteorites,” they wrote in the Science paper detailing the find.

With this find, researchers were confident that the Johnstown meteorite and others like it had come from Vesta. Before confirming this connection, researchers had only linked meteorites to the Moon, Earth, and Mars.

Binzel describes the Johnstown rock not as the meteorite that launched a thousand ships, but one that instead launched one major mission to the asteroid belt. In July 2011, NASA’s Dawn spacecraft reached Vesta and entered orbit around it.

Homecoming for the Johnstown meteorite

The folks in Johnstown weren’t the only ones to witness a piece of space coming to Earth that day in 1924. At least four of the meteorite’s pieces were seen falling, landing within an area some 10 miles by 2 miles (16 kilometers by 3 kilometers).

The 12-pound (5.4 kilograms) Johnstown meteorite was purchased by the Denver Museum of Nature and Science (then the Denver Natural History Museum) from the cemetery chapel for $100 and has resided in the museum ever since. About a week after the meteorite crashed to Earth, an even larger piece, weighing 52 pounds (23.5 kg), was found near the Big Thompson River; this piece is now at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. The other pieces are on display in Arizona and Illinois.

On its 100th Earth birthday, the Johnstown meteorite received a plaque to commemorate its fall and subsequent contributions to science. Those who attended the ceremony sang “Happy Birthday” to the special space rock.

“To me (I’m a scientist), it’s the scientific link that makes it so incredibly special,” says Binzel. “And then the fascinating history of it, the story of its fall, is the icing on the cake.”

Editor’s Note: This article has been updated to reflect that the meteorite fell in the afternoon, not the evening.