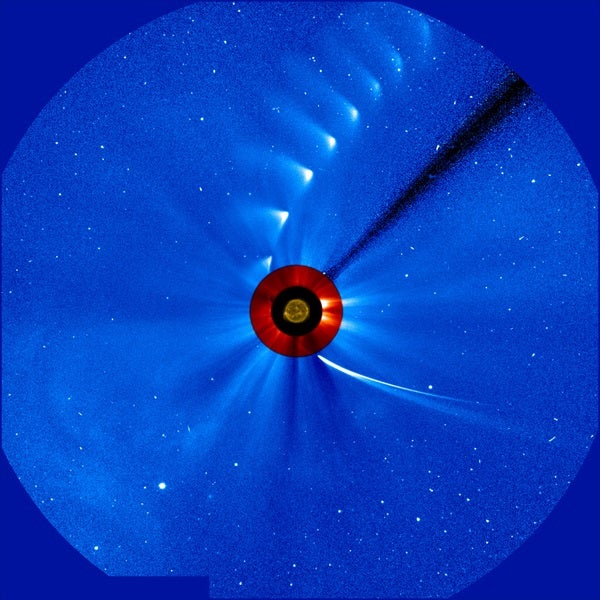

As the comet approached perihelion (its least distance from the Sun) November 28, it continued to brighten at roughly the rate astronomers had predicted. Late on the evening of the 27th (in North America), ISON peaked at magnitude –2.0. Images from coronagraphs aboard both the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) and the Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO) showed the comet as a bright point of light trailed by one distinct dust tail and a narrow dust streamer.

But ISON started to fade even before its closest approach to the Sun. The Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), which is equipped with the best cameras for close-up observations of our star and its surroundings, failed to see the comet at perihelion. And once ISON had moved far enough beyond the Sun that it could reappear in SOHO’s coronagraphs, it was nowhere to be found.

As astronomers began to write their post-mortems, however, the unpredictable comet rose from the dead like the legendary Phoenix. Some 24 hours after perihelion, SOHO once again captured images of ISON showing a thin dusty tail and a diffuse central condensation that some interpreted as a small remnant of the comet’s nucleus. But the revival soon began to peter out — by late on November 29, the glow had faded to around 6th magnitude.

It appears that the show amateur astronomers were hoping ISON would produce once it emerged from the Sun’s glare in early December won’t take place. Most scientists think the nucleus has dissipated, and any remaining dust likely will be too faint to see through anything but large telescopes. Even though ISON’s saga seems over, astronomers will spend months poring over their observations of this one-of-a-kind visitor.