The Georgia Tech simulations investigate the possibility that these red giants were dimmed after they were stripped of tens of percent of their mass millions of years ago during repeated collisions with an accretion disk at the galactic center. The very existence of the young stars, seen in astronomical observations today, is an indication that such a gaseous accretion disk was present in the galactic center because the young stars are thought to have formed from it as recently as a few million years ago.

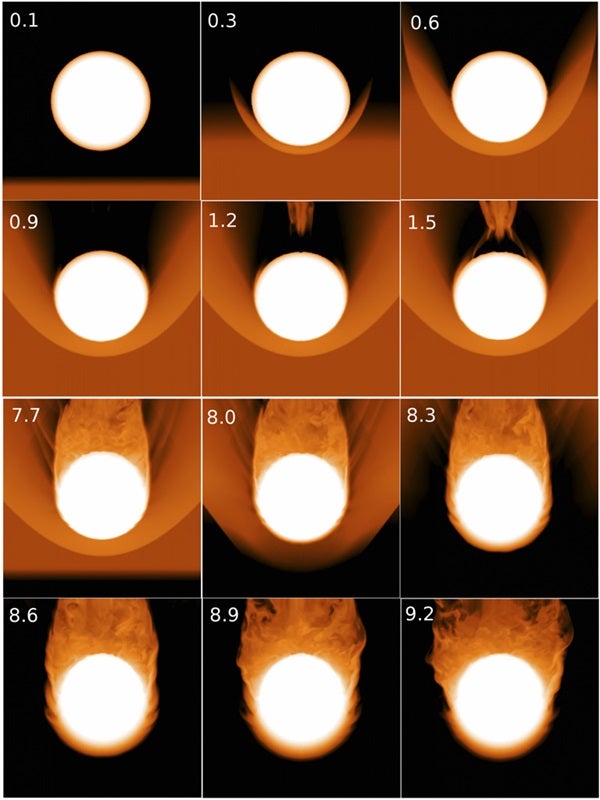

Astrophysicists in Georgia Tech’s College of Sciences created models of red giants similar to those that are supposedly missing from the galactic center — stars that are more than a billion years old and tens of times larger in size than the Sun. They put them through a computerized version of a wind tunnel to simulate collisions with the gaseous disk that once occupied much of the space within .5 parsecs of the galactic center. They varied orbital velocities and the disk’s density to find the conditions required to cause significant damage to the red giant stars.

“Red giants could have lost a significant portion of their mass only if the disk was very massive and dense,” said Tamara Bogdanovic from Georgia Tech. “So dense, that gravity would have already fragmented the disk on its own, helping to form massive clumps that became the building blocks of a new generation of stars.”

According to former Georgia Tech student Thomas Forrest Kieffer, it’s a process that would have taken place 4 to 8 million years ago, which is the same age as the young stars seen in the center of the Milky Way today.

“The only way for this scenario to take place within that relatively short time frame,” Kieffer said, “was if, back then, the disk that fragmented had a much larger mass than all the young stars that eventually formed from it — at least 100 to 1,000 times more mass.”

The impacts also likely lowered the kinetic energy of the red giant stars by at least 20 to 30 percent, shrinking their orbits and pulling them closer to the Milky Way’s black hole. At the same time, the collisions may have torqued the surface and spun up the red giants, which are otherwise known to rotate relatively slowly in isolation.

“We don’t know very much about the conditions that led to the most recent episode of star formation in the galactic center or whether this region of the galaxy could have contained so much gas,” Bogdanovic said. “If it did, we expect that it would presently house under-luminous red giants with smaller orbits, spinning more rapidly than expected. If such population of red giants is observed, among a small number that are still above the detection threshold, it would provide direct support for the star-disk collision hypothesis and allow us to learn more about the origins of the Milky Way.”