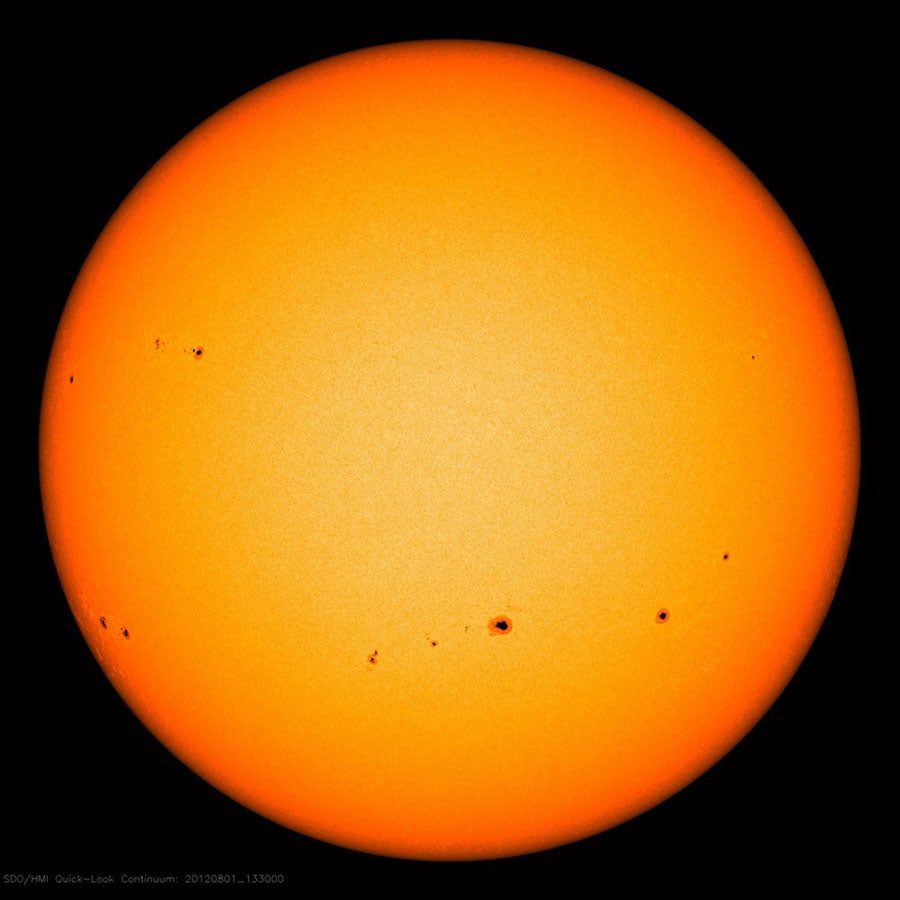

The Maunder minimum, between 1645 and 1715, when sunspots were scarce and the winters harsh, strongly suggests a link between solar activity and climate change. Until now there was a general consensus that solar activity has been trending upward over the past 300 years (since the end of the Maunder minimum), peaking in the late 20th century — called the Modern Grand Maximum by some.

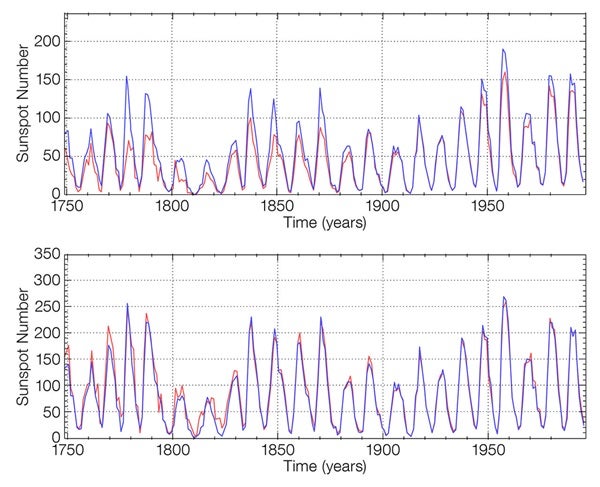

This trend has led some to conclude that the Sun has played a significant role in modern climate change. However, a discrepancy between two parallel series of sunspot number counts has been a contentious issue among scientists for some time.

The new correction of the sunspot number, called the Sunspot Number Version 2.0, led by Frédéric Clette, director of the World Data Centre–SILSO, Ed Cliver of the National Solar Observatory, and Leif Svalgaard of Stanford University, nullifies the claim that there has been a Modern Grand Maximum.

The results make it difficult to explain the observed changes in the climate that started in the 18th century and extended through the Industrial Revolution to the 20th century as being significantly influenced by natural solar trends.

The sunspot number is the only direct record of the evolution of the solar cycle over multiple centuries and is the longest scientific experiment still ongoing.

The apparent upward trend of solar activity between the 18th century and the late 20th century has now been identified as a major calibration error in the Group Sunspot Number. Now that this error has been corrected, solar activity appears to have remained relatively stable since the 1700s.

The newly corrected sunspot numbers now provide a homogenous record of solar activity dating back some 400 years. Existing climate evolution models will need to be reevaluated given this entirely new picture of the long-term evolution of solar activity. This work will stimulate new studies both in solar physics (solar cycle modeling and predictions) and climatology, and can be used to unlock tens of millennia of solar records encoded in cosmogenic nuclides found in ice cores and tree rings. This could reveal more clearly the role the Sun plays in climate change over much longer timescales.