The team has further shown how such discoveries of supernovae of type Ia (SNIa) can be made far more common than previously thought possible. SNIa seen through gravitational lenses can be used to make a direct measurement of the universe’s expansion rate — the Hubble parameter — so this discovery may have a significant impact on how cosmic expansion is studied in the future.

SNIa are tremendously useful to understand the mysterious components of the universe such as dark energy and dark matter. SNIa have strikingly similar peak luminosities, regardless of where they happen in the universe. This property allows astronomers to use SNIa as standard candles to measure cosmological distance independent of the universe’s expansion. Distance measurement with SNIa was key to the discovery of the accelerating expansion of the universe.

In 2010, scientists found a supernova named PS1-10afx that demonstrated the same color and light curve — the change in brightness over time — as a type Ia supernova, but its peak brightness was 30 times greater than expected. This discovery was made using the Panoramic Survey Telescope & Rapid Response System 1 (Pan-STARRS1), a telescope located in Hawaii that can image the entire visible sky several times each month. This anomaly led some to conclude that it was a completely new type of superluminous supernova. “PS1-10afx looked a lot like a type Ia supernova, “ said Quimby, “but it was just too bright.”

The physics of SNIa have been studied in detail over the past three decades, and there is no known way to produce a SNIa with normal colors and a normal light curve but a substantially higher luminosity.

“Generally, the rare supernovae that have been found to shine brighter than type Ia usually have higher temperatures (bluer colors) and larger physical sizes, and thus slower light curves,” Quimby said. “New physics would thus be required to explain PS1-10afx as an intrinsically luminous supernova.”

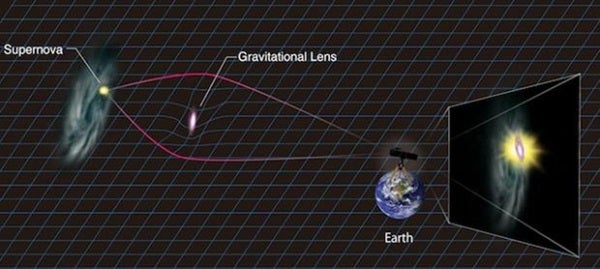

“We found a second explanation, and it required only well-demonstrated physics — gravitational lensing,” said Marcus Werner from the Kavli IPMU. “If there was a massive galaxy in front of PS1-10afx, it could warp space-time to form magnified images of the supernova.”

“Although the available observations were consistent with the hypothesis of our team, we needed to answer the question: Where was the lens galaxy?” said Anupreeta More from the Kavli IPMU, “The existing data clearly showed the presence of the supernova’s host galaxy, but there was no evidence for the necessary foreground galaxy. We then tried to find the evidence.”

In September 2013, Quimby’s team set out to find the hidden lens. Using the Low-Resolution Imaging Spectrograph on the 10-meter Keck-I Telescope located in Hawaii, they spent seven hours collecting light at the location of PS1-10afx, which had by then faded away itself.

“After carefully extracting the signal from the data, we had confirmation,” More said. “Buried in the glare of the relatively bright host galaxy, we found a second foreground galaxy. This second galaxy was faint enough to have previously gone unnoticed. But our analysis showed that it was still the right size to explain the gravitational lensing of PS1-10afx.”

“We had existing predictions of what a gravitationally lensed type Ia supernova would look like,” said Masamune Oguri from the Department of Physics at the University of Tokyo. “But the small size of this lens galaxy and the large magnification it produced was not exactly what we were expecting for the first discovery. However, this system may very well prove typical of discoveries to come. Because more distant supernovae are more likely to be gravitationally lensed, lensed supernovae are typically highly magnified and located in the distant universe.”

A consequence of this is that most of the gravitationally lensed SNIa that will be found with future surveys using instruments such as the coming Large Synoptic Survey Telescope can be identified by their colors — the higher redshift, gravitationally lensed supernovae being redder than the more nearby unlensed objects. “Our new approach allows us to find unresolved strong lensing events produced by such low-mass galaxies,” said Oguri. “Thus, the expected number of gravitationally lensed type Ia supernovae to be found in future surveys increases by an order of magnitude.”

“In the future, when a target is identified as a possible lensed type Ia supernova,” said Quimby, “high-resolution follow-up observations can be taken to resolve the individual image components.” Each image comes from the same source but travels a different path length on its way to the observer, so there is an arrival time difference between these multiple supernova images. If this “time delay” can be measured, a direct test of cosmic expansion is possible, faster expansion leads to shorter time delays. By timing the delays precisely and comparing these to the delay expected from the geometry of the lens, the expansion history of the universe can be directly inferred. “The discovery and selection method we have crafted may thus soon improve our understanding of our expanding universe,” Quimby said.